Have you ever given much thought to the subconscious mind? Until recently, I hadn’t. I thought it was a Freudian concept, or something nebulous to do with dreams. Now, my wellness-skewed algorithm throws up the term near daily, and it’s crept into conversations with my most normal of friends.

If you listen to any of the leading guest-interview podcasts, such as The Mel Robbins Podcast, Huberman Lab or Feel Better, Live More with Dr Rangan Chatterjee, you’ll hear neuroscience and psychology speakers say that it holds the key to changing our lives. Spirituality and manifestation gurus, even qualified money experts, describe it as our best friend or secret saboteur. Why? Because our subconscious holds beliefs about ourselves and the world.

Maybe you want to be famous but fear public speaking – subconscious beliefs could be holding you back. Can’t secure a job interview? Your subconscious might be blocking your efforts. Struggling to lose weight? You might believe you don’t deserve to. The idea is that even if you consciously want something, conflicting subconscious beliefs can sabotage it.

Take money: say you want £50,000 in the bank but are deep in debt instead. A subconscious belief could be as complex as, “After my dad got a big raise, my parents immediately divorced, so any increase in money feels unsafe,” or as simple as, “I don’t deserve to be happy.” Your subconscious “programming” is shaped by everything that’s happened to you: your habits, life experiences, upbringing and culture.

There’s a statistic that often accompanies this theory: “Our subconscious mind controls about 95 per cent of our behaviour.” When I first saw this written in a leading podcast host’s Instagram caption, I was shocked. What was this all-powerful, shadowy agent of chaos? Each time the phrase came up via enormously popular self-help figures like Dr Joe Dispenza and Dr Bruce Lipton, I was disturbed by it. We like to believe we’re individuals, making our own choices – but are we really being governed that heavily by an unhelpful force? It was all very Nineteen Eighty-Four, except we are our own totalitarian overlords.

In reality, the three neuroscience and psychology experts I spoke to all say this statistic was inaccurate, despite the number of voices who repeat it. “I think it’s really, really difficult to put a percentage on it, because it’s something that’s not known,” explains neuroscientist Dr Tara Swart, author of the upcoming book, The Signs: The New Science of How to Trust Your Instincts. “You could say something like ‘a large amount of our behaviours are driven by these subconscious beliefs’. Obviously, the more psychological work people have done, the more aware they are of what’s below consciousness.”

The reason the exact stat is unknown is because the subconscious mind itself is so unknown, argues Dr Devin Terhune, a reader in experimental psychology at King’s College London. “There’s still debate and controversy about the notion of subconscious,” he says. “There’s clearly cognitive processing occurring outside of awareness that is very likely to impact our behaviour and our experience of the world. But we don’t have a comprehensive understanding about how systematic that is.”

While not something to repeat verbatim, the experts suggest that the quote is, however, a useful metaphor. In his book, Thinking, Fast and Slow, Nobel Prize winner Dr Daniel Kahneman introduced the concept of a dual-process theory of the mind. System 1 is fast, automatic, subconscious thinking and driven by patterns and instincts. System 2 is slow, effortful, conscious thinking. Though he doesn’t give a percentage to that subconscious thinking, he nevertheless argues that the subconscious – system 1 – drives most day-to-day decisions.

When it comes to making a series of automatic decisions – like while driving or quickly judging that someone might pose a threat – this system can be ideal. It’s less helpful when you only seem to be attracted to grossly unavailable people. Or when you absentmindedly buy something on Vinted every time you feel empty inside.

The happy news is that it is very possible to change our subconscious mind: the idea of “reprogramming our subconscious” (to use the phrase du jour) is essentially the science of neuroplasticity, argues Swart. Neuroplasticity is the brain’s ability to form new neural connections and reorganise existing pathways in response to things like learning, experience or injury.

Swart breaks down her process for reprogramming your subconscious mind into four steps: awareness, focused attention, deliberate practice, and accountability. The first step – awareness – is about noticing your thoughts and identifying the deeper beliefs behind them. Then comes focused attention, which means paying attention to how those beliefs are influencing your behaviour – where they’re holding you back or driving your actions. Next is deliberate practice, where you actively start changing your behaviour to align with the new belief you want to adopt. Finally, accountability is about making sure you stick with it. Over time, this process helps you rewire unhelpful beliefs.

There are only certain things you can change in the subconscious, though, Dr Dan Siegel, executive director of the Mindsight Institute and co-director of the Mindful Awareness Research Center at UCLA, tells me. But not before he cautioned, “Let’s use the word ‘influence’ or ‘alter’ rather than ‘reprogram’ – ‘reprogram’ sounds too much like a computer metaphor.” No matter how much we want to believe otherwise in this age of AI and self-optimisation, we are not machines. The mind, he says, doesn’t live only in the brain either – it’s relational and embodied, including the brain and nervous system.

Temperament, for example – formed deep in the brainstem before birth – is something we can’t change. “You’re born with a temperament that non-consciously influences your motivation and emotions. That shapes personality. But how you adapt to it happens in the limbic area and cortex. That part is changeable. So the phrase ‘you can reprogram your subconscious mind’ needs qualifications. More accurately, you can influence certain aspects of energy flow in your nervous system that are changeable.”

Relationships are a key area where transformation is possible. “You can grow up in a hostile, abusive environment. That trauma embeds in your nervous system outside of awareness – what we’d call subconscious – and continues to affect you. As a therapist, I work to influence those patterns so that the chaos or rigidity they cause can be released.”

Cultural narratives also shape the mind – from family, society, and social media. Siegel believes we should challenge ideas that no longer serve us, especially those disproven by science, like “money buys happiness” or “we are just our bodies”. But changing these beliefs isn’t as simple as wiping a hard drive, though it would be nice if it were.

There are many practices aimed at changing beliefs, including affirmations, visualisations, hypnosis, EFT (tapping on meridian points – locations on the body that are central to traditional Chinese medicine – with verbal affirmations), and journaling to uncover limiting beliefs. These methods can obviously seem unusual, especially since they aim to bypass the conscious mind and influence deeper, subconscious patterns. While many of these techniques lack strong scientific validation and are often labelled as pseudoscience, some studies suggest potential benefits, particularly when they increase self-awareness or reduce stress. Anecdotally, many people report positive experiences.

When I did rapid resolution therapy (RRT) with practitioner Daniela Alfieri, the combination of light hypnosis and her dream-logic reframing felt soothing. She guided me back to past experiences and even to an old flat I’d shared with an ex, helping shift how I felt about them. Later, I tried an EFT session with Mos Jef, a cognitive repatterning specialist. As I tapped on acupuncture points, answered questions, and repeated phrases, I felt myself sinking into murky beliefs and emotions. He created space for me to voice sad, unconscious thoughts and feelings. Where did they come from? I had never consciously thought them before.

What I really wanted, though, was to learn a method that I could use myself at home to continue to change beliefs, so I went on a Psych-K course to learn how to be a facilitator. Course instructors Cazzie Dare and Sharon Lock explained that Psych-K is not a quick fix, although results can sometimes be felt immediately. During a process known as a “balance”, both hemispheres of the brain are brought into alignment, creating what they call a “whole-brain state”. In this state, the subconscious mind is more receptive, allowing limiting beliefs to be replaced with new, supportive ones.

Though tempting, the idea of Psych-K was not to sit for three intense days balancing everything with the intention of becoming a billionaire with a new romantic partner and a transformed outlook on life by the end of the week (though those goals were hypothetically very possible to work on). Instead, the other students and I were invited to look at what was happening in our lives right now: where was there conflict or an imbalance? What wasn’t working in our lives? From there, we mentally pivoted to what we wanted to experience instead.

For example, if you burst into tears during your annual appraisal with your boss, later that day, you might reflect and realise you often cry inappropriately and preemptively whenever you feel criticised. You could then decide to balance for the belief: “I stay calm and open whenever my behaviour is assessed by others and it is safe to do so.” Crucially, you don’t need to analyse why you get so emotional in these situations or what past experiences might have informed this – you only need to know what you’d rather experience. “We’d be there forever if we tried to identify all the limiting beliefs,” says Dare. “In Psych-K, we don’t need to know the root cause of something either in order to make the change.”

The process took a few days to learn through practising on ourselves and others. It included several parts, such as muscle testing to check whether our subconscious and “superconscious” minds permitted a change, physical movements to help achieve a whole-brain state, and short scripts to guide the process. The superconscious was described as a higher aspect of consciousness or inner wisdom that oversees your wellbeing and ensures any changes made are safe and appropriate for you.

Curiously, the superconscious mind will sometimes say no to things. When I muscle tested myself to see whether my superconscious considered it safe for me to balance for “I am calm and confident when I have money in my bank account,” I got a positive response (a stiff, immovable leg). But when I muscle tested to see if it was appropriate for me to balance for “I am calm and confident when my bank account is empty,” my leg bowed in easily. At first I was surprised. Wouldn’t it be more monk-like and worthy for me to be OK no matter what? After all, that’s what manifestation is all about: believe and act “as if” all is as you desire. But it wasn’t difficult for me to guess that my already laid-back relationship with said account being woefully empty is no longer helpful. I apparently need that jolt of adrenaline to make positive changes to my spending.

An important final step after a successful balance is to create an action step that supports that belief, which reminded me of what Swart had said. It shows your subconscious that you’re serious about this change and reinforces the new neural pathways you’re creating.

In the following weeks after the training, I found that the more niche and specific my balance statements were, the more obvious and traceable the results became, often within a short time. Possibly my most peculiar balance was for the belief: “Scriptwriting is as second nature to me as doing a simple Q&A article.” As a journalist of 15 years, interviewing someone and typing up the conversation in Q&A format is something I could do gravely ill and blindfolded. Writing a script for fun, a much more creatively demanding process, usually involves handwringing and cartoonish pacing around my office. One day, while screenwriting, I realised my overthinking had vanished. It had felt effortless all morning. My subconscious had clearly logged traces of the scriptwriting books I’d read and films I’d watched. At the very least, the stress I’d mentally attached to the task had disappeared.

Perhaps what’s most noticeably changed in me is my idea of the subconscious as an evil mastermind. I found that engaging with it could be playful and easy. If you can be open-minded – and, considering where the science is currently, you do have to be receptive to radical new ideas – you might be surprised by what you learn about yourself.

“Why does science have to prove everything?” Swart tells me at the end of my call with her, after I’d run her through a few of the methodologies I’ve mentioned here in this article. “If something makes you feel better, why is that not OK? Meditation: there wasn’t science for that 10 or 15 years ago, and there is now. But that doesn’t mean that it wasn’t helping people that were doing it before. I think with the subconscious, a lot more is going to emerge that we actually don’t know.”

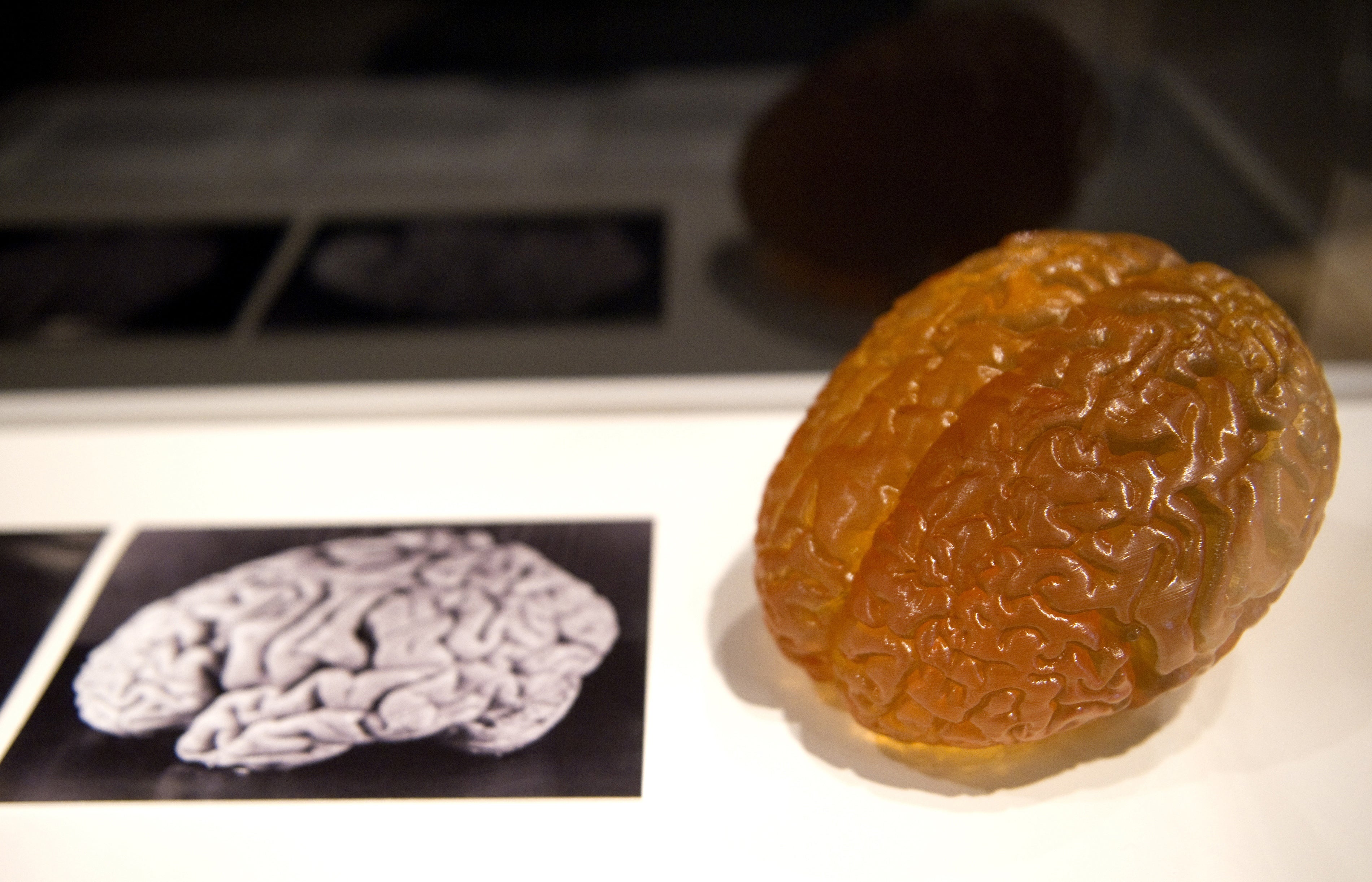

Illustration by Molly Benge