Way back when decent folk could be relied on to keep the notes in their chords in scale order (Root on the bottom, then 3rd then 5th ascending), it was deemed necessary to find a name for the different permutations that occur when this order was intentionally changed.

In this case, we’ll take a look at what happens when the 3rd is shifted to the bottom, replacing the Root as the lowest note. Though still theoretically the same chord, the sound is different enough to warrant acknowledgment in the name.

In classical circles, this would be known as a first inversion, but in most other styles that are played these days, we’d refer to it as a slash chord: for example, a G major with the 3rd at the bottom would be called G/B.

As a guitar player, you may not always feel it necessary to conform if the bass player is already covering the 3rd, but it can never be a bad thing to know your triads and inversions!

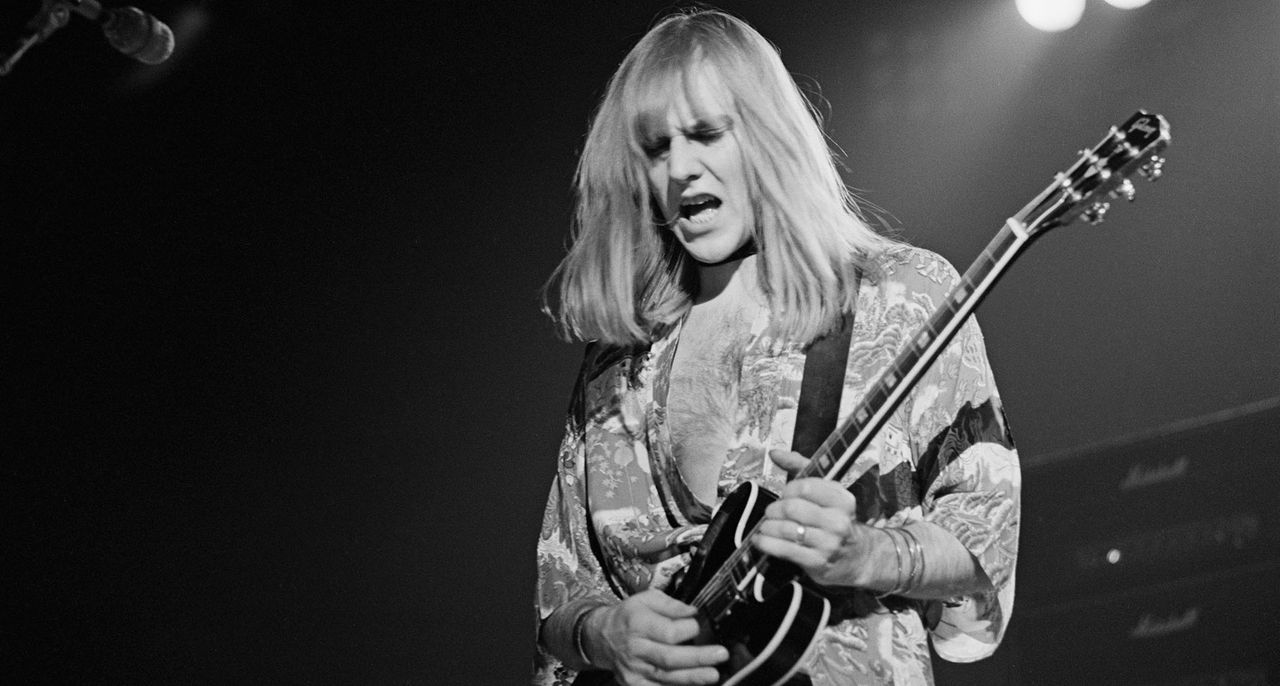

Example 1. E/G#

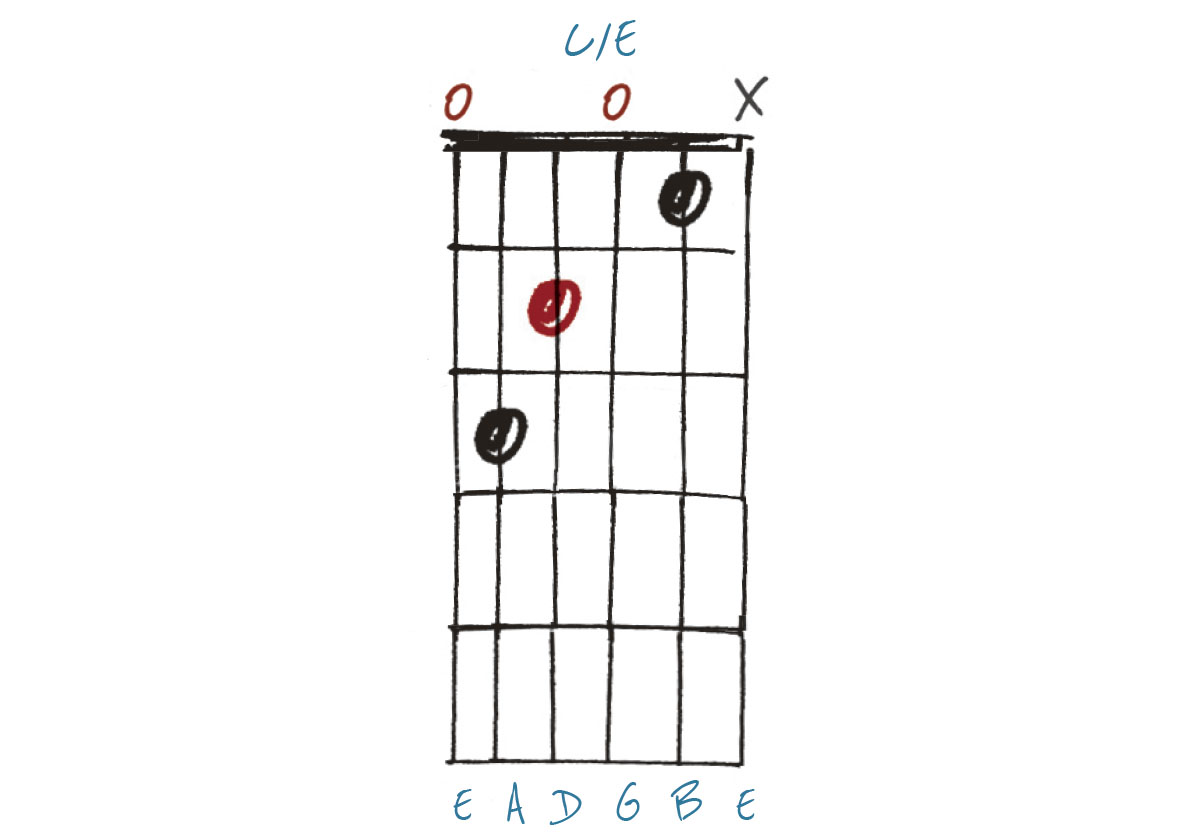

This E/G# follows the first inversion convention of having the 3rd (G#) on the bottom. This necessitates muting the fifth string as this would clash. We also get a nice bit of natural chorusing from the duplicated B (5th) on the third and second strings. 1970s-era Alex Lifeson was very fond of this voicing.

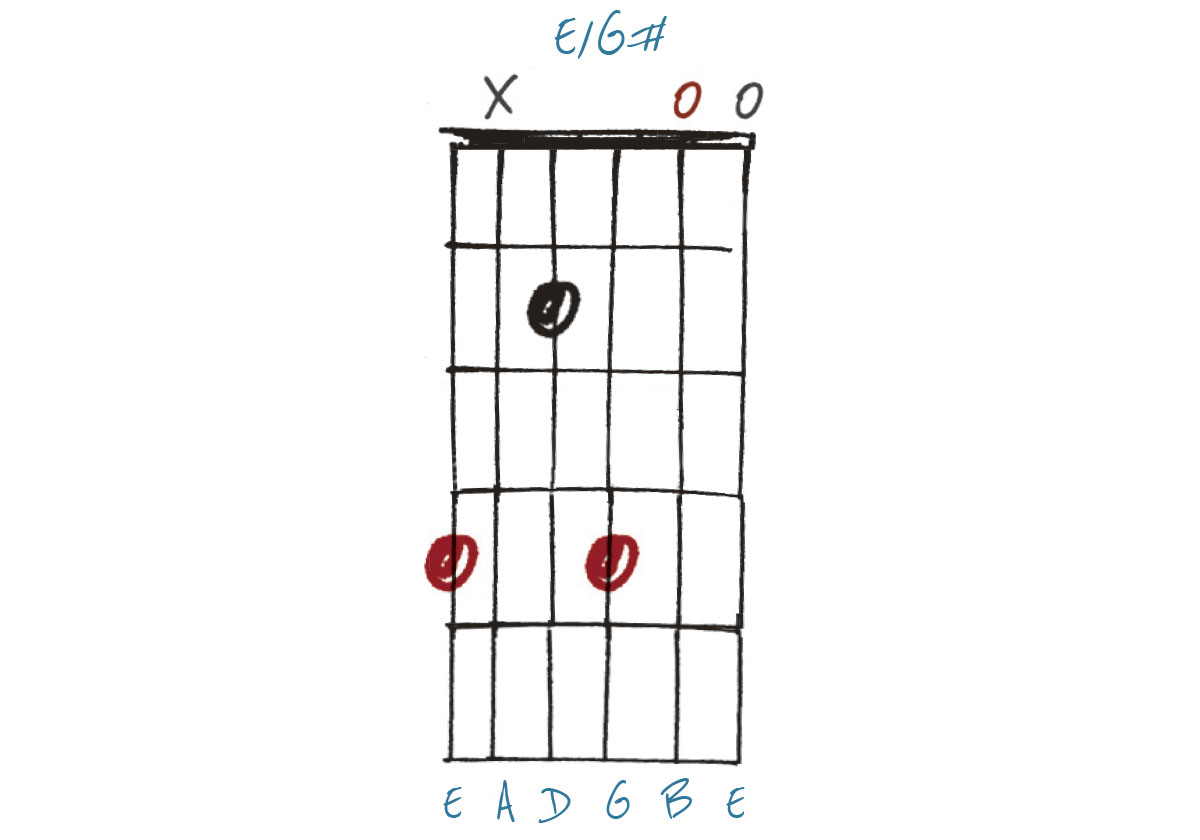

Example 2. D/F#

This D/F# (or first inversion) chord takes the 3rd (F#) from the first string and shifts it to the sixth string. The open fifth string would add in an A (5th), too, but for clarity it is muted here. Try both – you’ll likely find both versions have their uses.

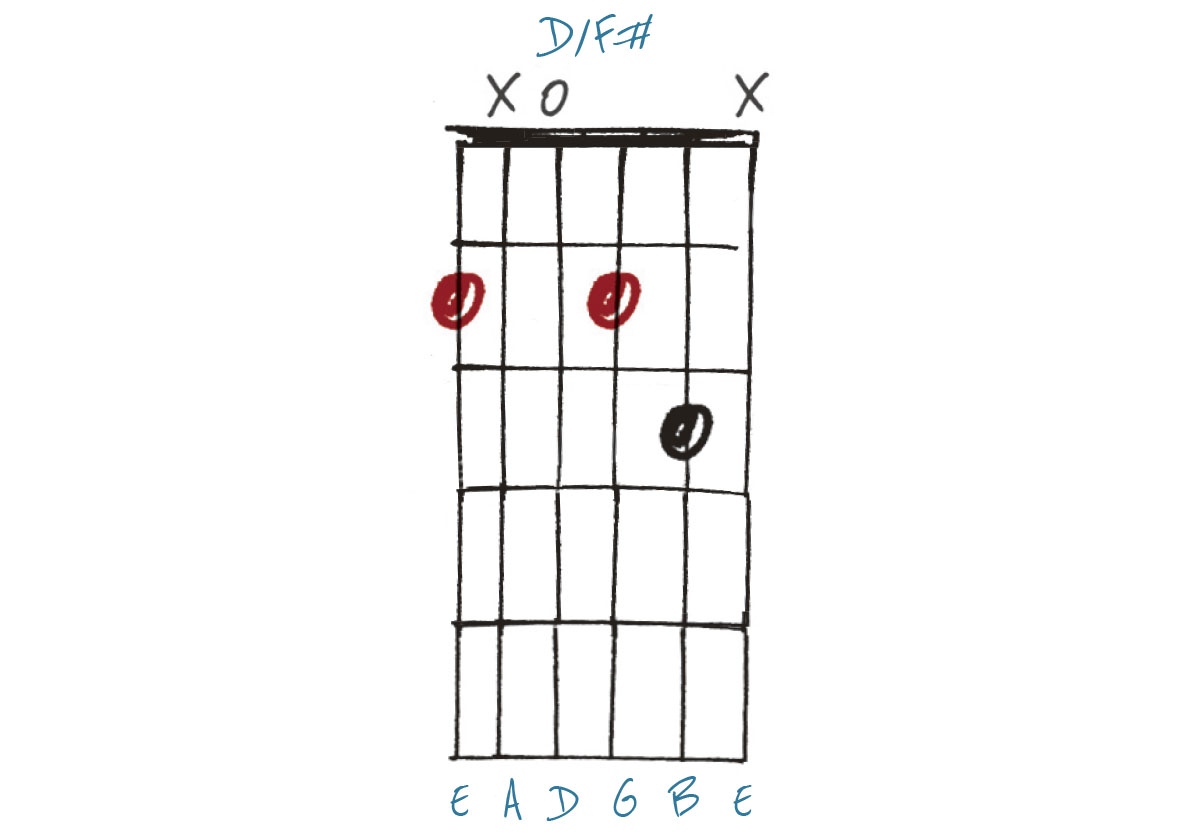

Example 3. C/E

Many of us will have been taught not to allow the sixth string to ring under an open position C chord! Now you can try it guilt-free and discover the joys of a C/E chord. Try playing an F major (or minor) chord following this and you’ll get an idea of how slash chords/inversions can work in context.

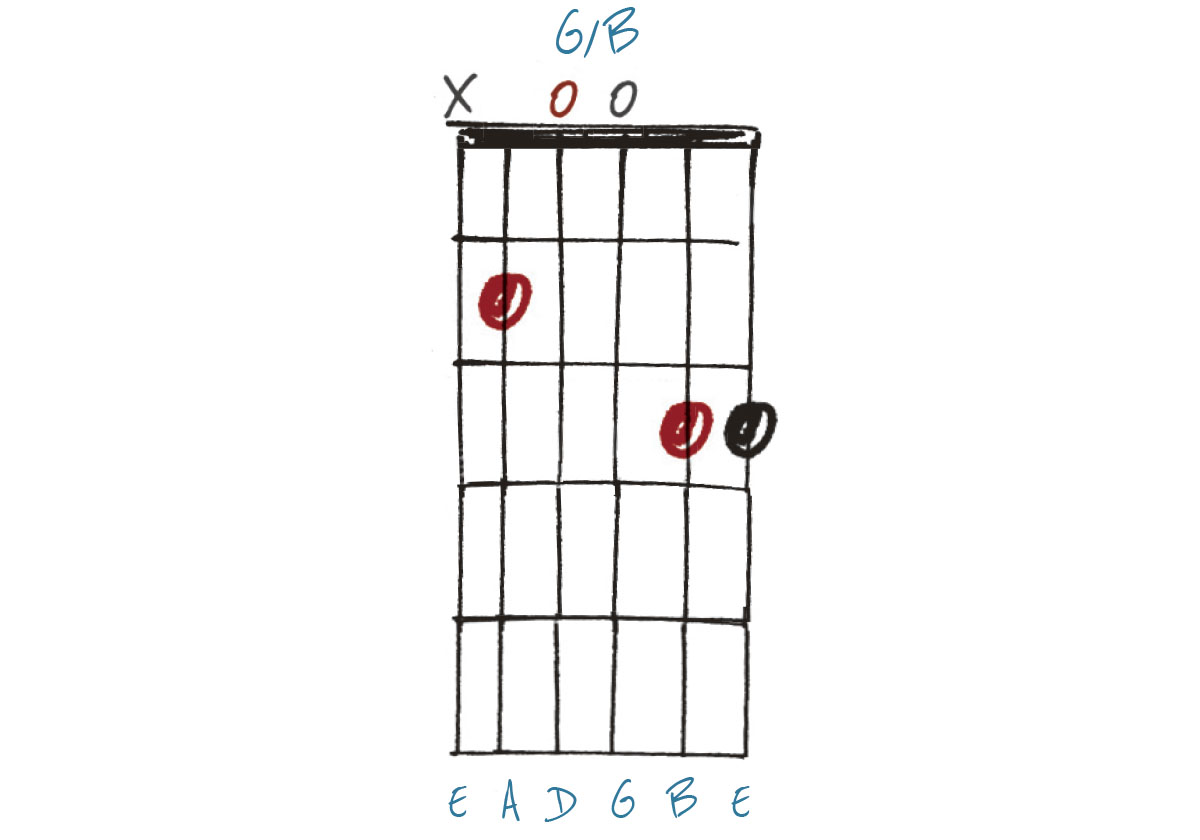

Example 4. G/B

While we’re looking at these open chord shapes, here’s a G/B. By omitting the usual Root (normally played at the 3rd fret of the sixth string as you almost certainly know), we shift the whole emphasis. Moving to a regular C major and back gives a classic chord move from many popular songs.

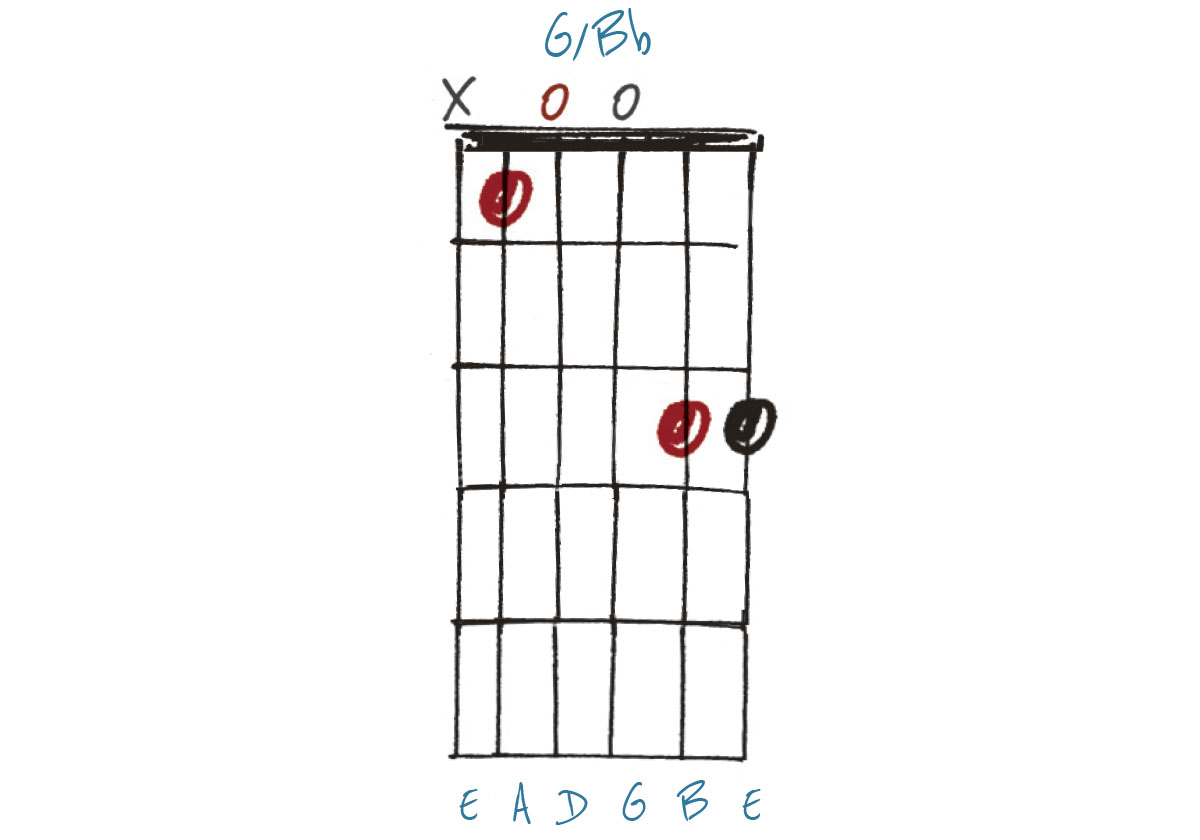

Example 5. G/Bb

So what about first inversion minor chords? Just like regular minor chords, the only difference is that we lower/flatten the 3rd by a semitone.

In this case, we’re calling it G/Bb – but we could also call it Gm (first inversion , or ‘inv’ for short). Try flattening the 3rd in the other examples (except maybe Example 3) and you’ll see they also work.

- This article first appeared in Guitar World. Subscribe and save.