The trial of British Isis fighter El Shafee Elsheikh, currently underway in Alexandria, Virginia, is one of the most significant terror trials of the last decade.

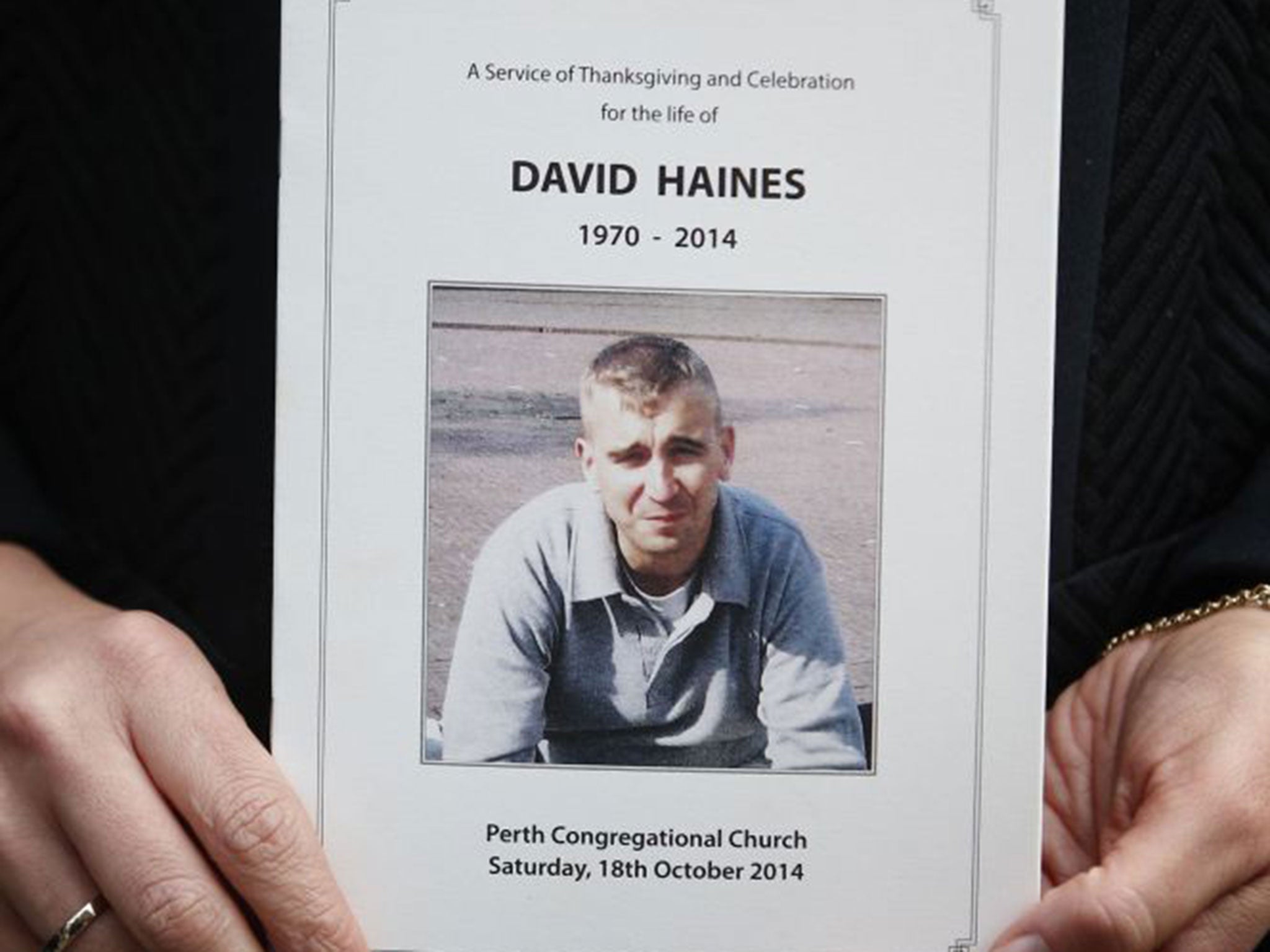

The 33-year-old Londoner is charged with involvement in a vast hostage-taking operation during his time with Isis in Syria, which ultimately led to the killing of American journalists James Foley and Steven Sotloff, and aid workers Kayla Mueller and Peter Kassig. The indictment also holds him responsible for the deaths of British aid workers David Haines and Alan Henning.

He is the most high-profile Isis fighter to face trial in the US, and his appearance in a federal court is the result of complex negotiations between Washington and the UK, which only agreed to share valuable evidence after a guarantee that prosecutors would not seek a death penalty.

One week in, the trial has already shone a light on the inner workings of the notoriously shadowy terror group and revealed new horrors.

The prosecution has focused on the role of three British Isis members who were named the Beatles by hostages because of their accents. They allege that Elsheikh was one of those three, with the other two being Alexanda Kotey and Mohammed Emwazi, an executioner known by his nickname ‘Jihadi John.’

Elsheikh’s defence lawyers have claimed that there is no proof that he was a member of the Beatles, despite him previously admitting to being a member of Isis and involvement in the hostage-taking scheme.

Here is what we have learned in the trial so far.

The Beatles were even more brutal than previously known

Isis publicised its most brutal acts of violence for propaganda purposes. But in the opening days of this trial we heard about the everyday acts of cruelty the Beatles inflicted on hostages they held.

The jury heard from one of the longest-serving hostages to survive Isis captivity. Federico Motka, an Italian aid worker, was kidnapped alongside his colleague David Haines as they were carrying out an assessment in northern Syria in March 2013. He was held by the group for 14 months.

Over several hours, he described how the three British Isis fighters they came to name the Beatles regularly beat him and other prisoners, tortured them, put them in stress positions and threatened them with murder.

“They egged each other on like school kids in a yard bullying someone,” Mr Motka said of the violence they regularly faced.

On one occasion, two men who they called George and Ringo, whom the prosecution alleged are Mohammad Emwazi and Elsheikh, waterboarded Mr Motka and Mr Haines. Ringo took his jumper and wrapped it around Mr Motka’s face, while George poured water over it to simulate drowning.

“I was trying to breathe out of the side of my mouth at first,” he said, but it didn’t work. He came close to passing out before they stopped. Then they subjected David Haines to the same treatment.

On another occasion, the three Beatles made Mr Motka and Mr Haines fight fellow hostages James Foley and John Cantlie in what they called a “Royal Rumble.”

The terrorists shouted orders at them through a grate in the ceiling to fight each other, while they jeered and gave mock radio commentary. They told the group that whoever lost would face waterboarding. The four were so weak and emaciated from a lack of food and poor conditions that two of them passed out.

“It was by far the worst thing that happened,” Mr Motka said of the waterboarding.

The torture they inflicted was psychological, as well as physical. The British jihadists seemed at times to revel in their brutality.

“They played lots of games with us,” Mr Motka said. “They gave us dog names and told us that if they called us day or night we had to respond.” The punishment for failing to do so was a beating, he added.

The court was later shown video of Emwazi executing a Syrian hostage in front of a group of western hostages. The video was sent to their families in order to put more pressure on them to comply with their demands.

The Beatles were central to the Isis hostage-taking scheme

The prosecution in the trial of Elsheikh has tried to show that the Beatles were central to the Isis hostage-taking operation.

The group is alleged to have been involved in the kidnapping of at least 27 people in Syria between 2012 and 2015, most of them Westerners.

Mr Motka testified that the three Beatles were present immediately after his capture, that they were there frequently throughout his detention, and would eventually deliver him upon his release. Elsheikh has also admitted in media interviews that he was involved with handling Western hostages since 2013, and those interviews have been shown to the court.

The court heard how the Beatles performed key tasks relating to hostage negotiations with the families. They would regularly solicit email addresses and personal information from their captives for the purpose of those negotiations, and ask proof of life questions when required by the families. Sometimes, to speed things along, the Beatles would force the hostages to film videos demanding money from their own families and warning that they would die if they did not comply.

The court was also shown videos of media interviews Elsheikh gave following his capture by US-allied Kurdish forces. He described on numerous occasions how he solicited email addresses from the hostages, and admitted how he helped with “logistics” regarding the hostages.

Elsheikh’s own words are being used against him

The Beatles went to great lengths to hide their identity from hostages throughout their captivity. Every time the three of them entered the room, hostages were forced to kneel and face the wall. They would always wear a balaclava. Those precautions might have made it hard for prosecutors to definitively link Elsheikh to the hostage scheme, had he not given numerous interviews admitting his involvement.

Those interviews are now a central part of the evidence being presented to the jury to prove his participation in the hostage-taking conspiracy. Numerous clips of media interviews given by Elsheikh have been played to the jury. In those interviews he named some of the western hostages whom he watched over, admitted to collecting emails for use in ransom notes and to beating them.

“I’ve hit most of the prisoners,” he told one interviewer, in a video shown to the court. “I did have transgressions. I did transgress physically,” he said, when asked about the beatings.

He also tried to justify his ill-treatment of prisoners by claiming it was necessary to keep prisoners in line because they didn’t have a proper facility to prevent them from escaping.

“Subduing prisoners is used as a preventative of escape,” he said.

Elsheikh’s defence team tried to have those videos thrown out of evidence, suggesting that he was forced by his Kurdish guards to give confessions during his detention. That motion was denied by the judge, who claimed wellness checks by US officials who visited him at the jail showed no signs of mistreatment.

The prosecution has also presented text messages which they claimed were sent from Elsheikh to his brother Khaled. In one of them, Elsheikh sent gruesome images of severed heads of Syrian soldiers, which he said had been displayed by Isis following a battle against the Syrian army.

“The roundabout is full of heads and bodies,” he said.

He also sent his brother an image of himself in “Rambo mode.” The picture shows him dressed in military gear and a tactical vest with a knife and a gun.

Jihadi George, or Jihadi John?

For some years now, the Isis Beatles have been referred to in media reports by their nicknames. Mohamad Emwazi was the most famous of the group, known to the world as Jihadi John. Alexanda Kotey was thought to be Ringo and Elsheikh was George. But those names don’t appear to be the same ones given to them by the hostages.

During opening statements, the prosecution team said they would prove that Elsheikh was known as Ringo. That moment caused a ripple of shock among journalists covering the trial, who thought Elsheikh was George.

That confusion was compounded during Mr Motka’s testimony when he said that Emwazi, the Isis executioner known to the world as Jihadi John, was known to them as George.

It may be that the media attributed different nicknames to the Beatles than the hostages, and they just stuck. Or it may be that different groups of hostages — who were held separately — assigned different names to them than each other.

In any case, the prosecution has not yet presented any former hostage who has identified Elsheikh as Ringo from the stand. They have instead focused more broadly on abuse and activities that all three Beatles took part in, and presented evidence to show that Elsheikh was one of the Beatles, without focusing on proving which one.

Often, when a witness is describing abuse, the prosecution has asked the question: “Did all the Beatles participate in this abuse?” To which the answer is usually yes.

This trial has been incredibly painful for the victims’ families

The victims named in the indictment against Elsheikh are James Foley, Steven Sotloff, Kayla Mueller, Peter Kassig, David Haines and Alan Henning. But this trial has been a reminder of the immense suffering the Isis hostage-taking scheme inflicted on their families.

As part of their effort to show how the operation worked, the prosecution has presented communications between the hostage-takers and the families of those they held.

They show how Isis captors made unrealistic demands of the families, chastised them for the actions of their governments and mocked them while they desperately sought information about their loved ones.

On Monday, the court heard from family members for the first time. Michael Foley, the younger brother of James, spoke about the last time he saw his brother, in October 2012. He took him to the train station, where he began his journey to Syria.

“We expected him home by Christmas,” Michael told the court.

On 22 November, James was abducted in northern Syria with fellow journalist John Cantlie. It would be a year until the first email arrived. The kidnappers demanded that the family pressure the US government to release “Muslim prisoners,” or alternatively deliver an impossible €100,000,000.

Soon after the hostage-takers went quiet. Michael and then his father John Foley made numerous pleas for any information about their brother and son, which were roundly ignored.

When the US launched airstrikes against Isis in northern Iraq to prevent the massacre of thousands of Yazidi civilians who had escaped an attack, the hostage-takers emailed the Foleys to tell them that their son would be executed as a result.

“As for the scum of your country who are held prisoner by us, THEY DARED TO ENTER THE LION’S DEN AND WHERE [sic] EATEN.

“He will be executed as a DIRECT result of your transgressions toward us,” the email said.

Isis would soon release a choreographed video that showed James Foley’s decapitated body. They called it a “message to America.”