In the first five months of 2025, 305 samples of a wide range of drugs – including lifesaving medication – drawn from pharmacies across Karnataka failed quality tests. Nearly a quarter failed more than one test, and almost half were injectable drugs. These tests were done by Karnataka’s Drug Control Department (DCD).

TNM found that the drugs flagged as Not of Standard Quality (NSQ) between January and May 27 included commonly prescribed medicines for cough, fever, high cholesterol, diabetes, high blood pressure, emergency drugs used during cardiac arrest, diuretics to increase urine production and reduce blood pressure, steroids to treat inflammation and autoimmune diseases, antibiotics, depression, anxiety, epilepsy, arthritis, alcohol de-addiction, and severe vomiting (such as in chemotherapy). Also among the failed samples were vitamins, antacids, antidotes for pesticides, and painkillers.

Most of the 153 manufacturing companies were based in Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh, Haryana, Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, and West Bengal. A handful were based in Tamil Nadu, Goa, Telangana, Jammu and Kashmir and Andhra Pradesh. Nine companies were based in Karnataka.

The manufacture, sale, import and quality control of drugs in India are governed by legal and scientific standards set by the Indian Pharmacopoeia (IP). Drugs that fail the quality tests prescribed in the IP are designated NSQ, as they pose varying degrees of risk to patients who consume them.

Under the Drugs and Cosmetics Act 1940, the DCD is supposed to test drugs from pharmacies across the state and initiate the recall of NSQ drugs so that the public does not consume them.

In this investigation, we inspected these lists and spoke to pharmacies to understand the recall process. Though government officials claim that recalling such drugs is a continual process, our conversations with pharmacies suggest that the system is simply not rigorous – meaning that people can still end up buying their medicines from unaware pharmacists with potentially adverse effects on their health.

Which drugs failed the tests?

Of the total NSQ drugs, 66 samples (22 percent) had failed tests for disintegration or dissolution – meaning that they do not disintegrate and dissolve in the blood as they are supposed to.

Several antacids, paracetamol, antibiotics, vitamins, painkillers, de-worming, and anti-emetics (to control nausea/vomiting), anti-anxiety and diabetes tablets were among the samples that had failed dissolution and disintegration tests.

Medicines used to control high blood pressure, such as a sample of Enacare 5 (enalapril maleate 5 mg) tablets, failed tests for assay and dissolution. The drug was manufactured by Uttarakhand-based Om Biomedic Pvt Ltd.

Failing the assay test means that the drug does not have the active ingredients in the prescribed quantities, while if a drug fails the dissolution test, it means that it does not dissolve in the blood the way it is supposed to.

Worryingly, nearly half –144 or 47 percent – of the total samples found to be NSQ were injectables, which can have far more immediate and adverse effects since they are directly released into the bloodstream.

Of the 144 injectables, about 85 percnet failed the test for sterility. Sterility means two things in the context of pharmaceutical tests: sterility of the containers used for certain products and procedural measures that must prevent contamination of biological materials.

Twenty-one samples had failed tests for bacterial endotoxins, particulate matter, or assay in addition to failing the sterility test.

Almost half of the 144 injectable samples were Ringer’s Lactate, mostly manufactured by West Bengal-based Paschim Banga Pharmaceuticals.

TNM had previously reported that the DCD was testing samples from all the batches of the state’s supply of Ringer’s Lactate manufactured by the company after it was suspected to have caused the deaths of six women in Ballari between November and December 2024.

While the Karnataka State Medical Supplies Corporation Limited (KSMSCL) procures drugs for use in state-run institutions, drugs sold in pharmacies are regulated by the Drugs Control Department.

Ringer’s Lactate, manufactured by other companies too, was flagged by the DCD. Two samples of Ringer’s Lactate manufactured by Ultra Laboratories, a Hassan-based company, failed sterility tests. Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, an Ahmedabad-based company that manufactures Ringer’s Lactate, was also flagged for failing the sterility test.

The 144 injectable drugs samples also included 42 samples of different types of intravenous fluids administered to keep the body hydrated or replenish fluid loss.

The remaining injectables that were NSQ included pain relievers (Diclofenac sodium injection made by Alpa Laboratories Ltd), vitamin B12 and calcium injections.

For instance, a sample of dexamethasone sodium phosphate injection manufactured by Himalaya Meditek, based in Dehradun, failed tests for assay, bacterial endotoxins, particulate matter and sterility. This compound is a steroid used to treat inflammation and autoimmune diseases.

Several injectable antibiotics used in a wide range of situations including surgery had also failed sterility tests.

The injectable drugs also included lifesaving medication used in the emergency treatment of very high blood pressure, those used to restore heartbeat in cardiac arrest cases, and drugs used to treat prolonged seizures.

Six samples of diabetes medicines by five different manufacturers failed either assay or dissolution tests, and in two samples, both tests. An estimated 77 million people suffer from diabetes in India, according to the World Health Organisation (WHO).

Same manufacturer, different district

The names of several manufacturing companies featured on the list more than once, either because a drug made by a company had been flagged from more than one district or because more than one of its products turned up NSQ.

For instance, three drugs made by Uttarakhand-based SVP Lifesciences were flagged for failing tests for assay, acidity, sterility and particulate matter. These drugs included Ivermectin Injection (used for parasitic infections), Atropine Sulphate Injection (emergency medication for cardiac arrest), and Vitamin B12 injection.

A handful of medicines had failed to conform to the US Pharmacopoeia (USP) or the British Pharmacopoeia (BP), the US and UK equivalents of the IP.

Aloe gel and leaking condoms

TNM found that one of the samples that came back NSQ was Avelia, an aloe vera gel made by Telangana-based Medplus Health Services Limited that failed a label claim test. Another was a condom manufactured by UP-based Anondita Healthcare that did not meet standards for burst pressure and water leakage.

While the DCD department publishes the batch numbers and reasons the sample failed quality tests, there are several unanswered questions. Here are two: How do drug inspectors decide which drugs or health products to test, and what is the full list of samples sent each month for quality tests?

These questions were raised in the book The Truth Pill: The Myth of Drug Regulation in India (2022) by Dinesh S Thakur and Prashant Reddy T.

Dinesh Thakur told TNM that the data they found for state drug testing labs in Gujarat, Maharashtra and Kerala suggested that a vast majority of drugs they tested were antacids.

“The reason for such lopsided sampling from the market is that we have no consistent sampling strategy for our testing. Injectables used in acute care should be tested far more frequently compared to antacids because the harm to patients from NSQ injectables is far greater than from NSQ antacids. We need to have a consistent way of sampling, testing and sharing results from all state drug testing labs across the country.”

Referring to the law mandating drug inspectors to buy drugs from pharmacies for quality testing, Dinesh said, “No individual state has enough money or analysts to effectively police our nation’s drug supply. Right now, the left hand does not know what the right hand is doing because the national regulator is dysfunctional. It fails miserably in its role as the coordinator of drug testing and data sharing across the states. This needs to be fixed as soon as possible.”

Asked about how the DCD chose which drugs to test, a government source said, “The DCD has a budget, and they have to work within that. Some drugs, like those for cancer, are very expensive. We are going to work out what drugs the department will test and how to go about it.”

Drug recall: How rigorous is it?

While the Health Department fixes these issues, there is a more important question of what is actually done with the drugs that come back NSQ.

An official in the DCD told TNM that the recall of drugs was a continual process.

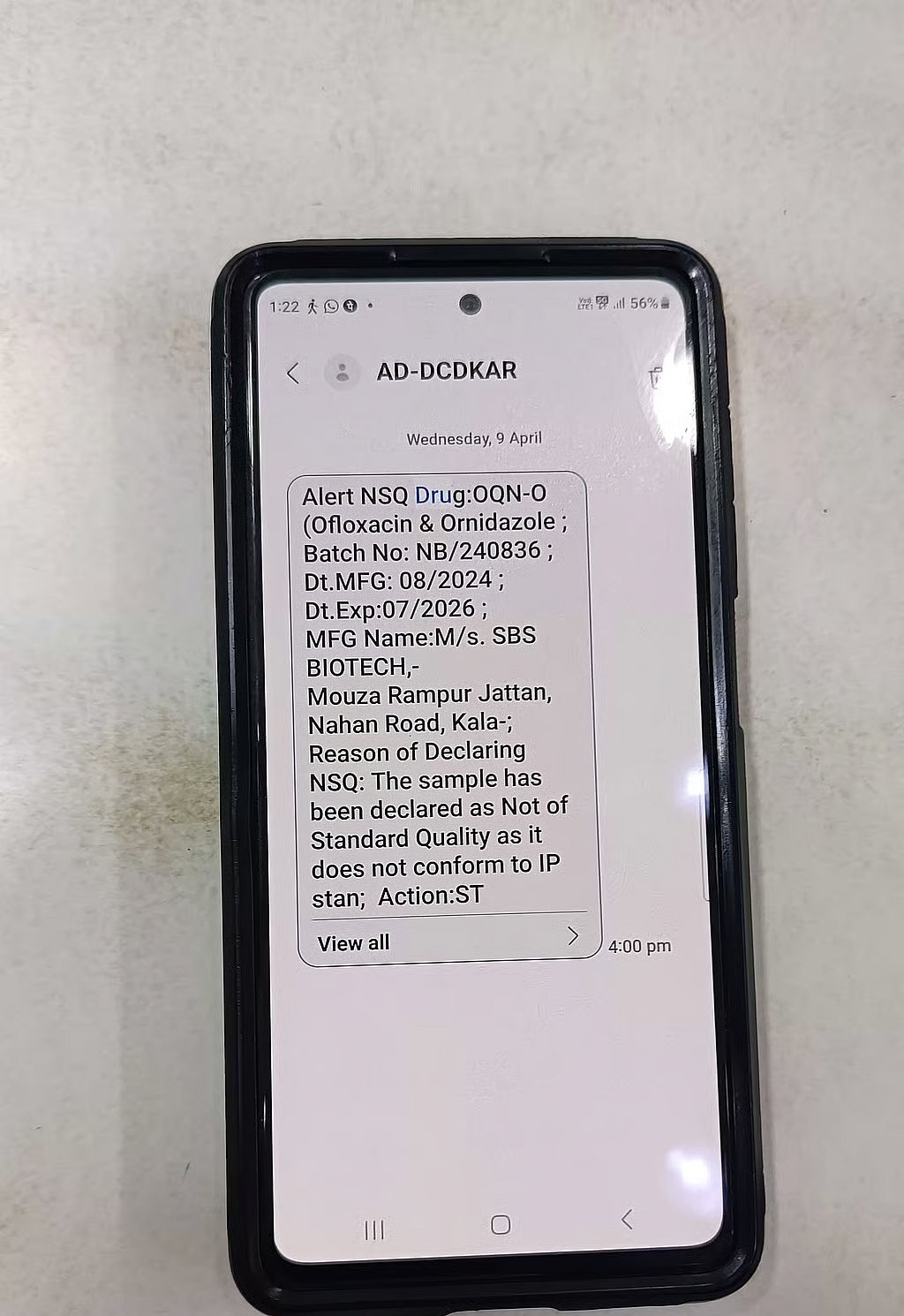

“Since 2015, we’ve had a messaging system in place. When a drug comes back NSQ, we send messages to pharmacies notifying them. We issue notices to dealers under Sections 18 and 18A of the Drugs and Cosmetics Act, and they are supposed to recall the drugs after that. We seize the drugs from the manufacturers, and they automatically become evidence in court cases. We destroy the drugs after the cases conclude,” the official said.

However, a check with nine pharmacies in three areas in Bengaluru revealed that this system is patchy.

A pharmacy near MG Road confirmed that the DCD sends out alerts. The owner of the pharmacy, who declined to be named, told TNM that the last such alert he had received was on April 9, for a drug called Ofloxacin and Ornidazole, manufactured by Himachal Pradesh-based SBS Biotech, along with the batch number, manufacturing and expiry dates, and reason for NSQ. It had failed the dissolution test. The NSQ result for this sample came back on March 28.

“Once we get the message, we’re supposed to send the stock back to the dealer, and they return it to the manufacturer. We keep one copy of the document that shows we returned stock, and the dealer has one copy. We give our copy to the DCD when they come for inspections,” the pharmacist told TNM.

Another pharmacist near MG Road told TNM that he was aware of the system but that the last notification he got was in 2015.

Three pharmacies near Brigade Road, two in Hulimavu, and one in Kengeri denied any knowledge of NSQ drugs and had never received any communication from the government about it.

Staff at an outlet of a well-known pharmacy chain in Kengeri told TNM that each outlet receives information about stopping sales of drugs based on information from the government. The manager showed TNM a list of drugs that they had been prohibited from selling by the management. However, this list too, did not have NSQ drugs.

“If the retail pharmacies have no idea of these alerts, imagine what information lay people have. This is precisely why I keep harping on a more proactive public outreach when the government finds NSQ drugs in their testing labs,” Dinesh Thakur said.

Health and Family Welfare Minister Dinesh Gundu Rao had told media in April that 41 drugs had been recalled, but DCD data shows that the number of NSQ samples is far higher.

Where lies the solution?

According to The Truth Pill, the lack of a law on drug recall is a story of “epic bureaucratic procrastination.” The first time that the Union government discussed drug recall was in 1976, three years after at least 15 children died in Chennai due to a cough syrup adulterated with diethylene glycol (DEG), a solvent that damages the kidneys. The same adulterant was found again 40 years later, in the cough syrup given to the 12 children who died in Jammu in 2019 and 2020.

Between 1976 and 2019, the Drugs Consultative Committee (DCC) and the Drugs Technical Advisory Board (DTAB), both bodies under the Drugs and Cosmetics Act, discussed a drug recall policy 10 times, according to The Truth Pill.

Meanwhile, the Drugs and Cosmetics Act 1940 was amended in 1982 to insert Section 18 to prohibit the sale of NSQ drugs. This amendment came into effect on February 1, 1983, but it is unclear what procedures are in place to ensure compliance from pharmacists, dealers and manufacturers.

In 2012, the Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation (CDSCO) published the Guidelines on Recall and Rapid Alert System for Drugs.

The guidelines note that there is no “accountability” about drug recall and that the purpose of these guidelines is to lay down “uniform procedure and execute statutory powers” under the Drugs and Cosmetics Act for “directing and ensuring rapid alert and effective recall/destruction of (NSQ) drug products.”

Ironically, even as the guidelines talk about the lack of accountability, they place the onus on the manufacturers: “These guidelines are expected to be followed by licensees (manufacturers, importers, stockists, distributors, retailers)... The procedure may also be used by the Drugs Control Authorities of central or state when urgent action is required to protect public or animal health.”

Despite all this, the guidelines are, for all practical purposes, all bark and no bite. There is still no legal obligation on manufacturers or any government authority.

This means that the public has no way of knowing whether pharmacists and manufacturers have actually taken every last tablet, vial, or bottle of a bad drug off the shelves.

A comparison with the US Food and Drug Administration (USFDA) throws some light on the role the government can play. “FDA’s role in a recall is to oversee a company’s recall strategy, assess the adequacy of the company’s action and classify the recall… FDA evaluates the effectiveness of a recall by reviewing a company’s efforts to properly notify customers and remove the defective product from the market. If a recall is determined to be ineffective, the FDA will request the company to take additional actions to protect patient health,” the USFDA website says.

When TNM asked Karnataka’s DCD about the CDCSO guidelines, officials only vaguely recalled that they existed but cited Section 18 of the Drugs and Cosmetics Act as the legal provision for drug recall.

Pioneering policy?

The Karnataka Health Department is looking into many of these concerns, according to government sources who confirmed to TNM that a drug recall policy has been prepared and sent to experts who have given their comments.

“It is not easy to frame a drug recall policy. There are several issues of jurisdiction that we need to look into,” said a source who is part of the drafting process. One issue in particular, he said, was deciding at what point the drugs would be recalled. “Once a drug is declared NSQ, the manufacturer can appeal the results with the Central Drugs Laboratory (Kolkata). How do we tackle that?”

If a drug fails a quality test done by a state government lab, the manufacturer can appeal the results at the Central Drugs Laboratory in Kolkata, which is the final arbiter of quality under the Drugs and Cosmetics Act.

The authors of The Truth Pill have written about the opaque manner in which CDL Kolkata functions and how, in several cases, a drug that has failed to pass muster at a state government-run lab is “miraculously” found to have met quality standards.

“We need to look into all these issues and get expert suggestions. We will release the draft policy to the public for comments after we finalise these issues,” the source said.

A tech fix

As the list of NSQ drugs grows longer, the DCD has directed its energies and resources to developing an app that will bring the DCD, wholesalers and retailers in Karnataka on the same platform to facilitate the recall of substandard drugs. Officials TNM spoke to said the app was being developed in-house, advised by external experts.

A DCD official told TNM that an Application Programming Interface (API) link will be sent to about 12,000 wholesalers and about 24,000 retailers in Karnataka. An API links two software programmes, allowing them to talk to each other. This would allow the software used by pharmacies and sellers to connect with the government portal. There are 11 lakh products, and all of them have to be integrated into the system, a DCD official told TNM.

“Once a drug is found to be NSQ, alerts will go out through the portal. Once we block it, the drug cannot be billed anywhere. First, we will get the wholesalers to register, and then the retailers. With this software, we can at least make sure that the drug is not sold anywhere,” the official told TNM.

The official said that trials have started and that they are also in the process of building digital protections for the app. The app is likely to be ready in a month.

Experts and activists, however, say that a tech-driven solution like this is simply inadequate.

Dinesh S Thakur told TNM that the Karnataka government needed to follow through on a drug recall policy. “The Health Minister has made a statement in the House that his department will formulate a policy for drug recall for the state. This is a commitment to the people of the state.”

He said that developing software is only a part of the government’s responsibility. “Public communication is a significant part that seems to be missing. Why is it that only when people die that we see officials speaking about this issue publicly? Why is it that they don’t inform the public every time they find an NSQ drug in their labs? Are they waiting for people to die before speaking out?” he asked.

While acknowledging that the legal framework does give the Union government more powers, Dinesh maintained that states are not entirely helpless.

“Karnataka is well within its rights to draft a policy on how the law can be implemented. For example, nothing prevents Karnataka from holding a public press conference when its labs detect failure among sterile injectables, which have a real risk of causing deaths, and making public statements about the manufacturer of that particular injectable,” Dinesh says.

Dinesh said that the Karnataka government could set an example by drafting a drug recall policy. “The state health ministry can force other states, leading by example on how it implements the act and making it hard for the Union to ignore these issues on the ground.”

President of Drug Action Forum-Karnataka (DAF-K) Dr Gopal Dabade told TNM that drugs procured for the public health system must be tested before they are cleared for use, as is being done in Tamil Nadu and Rajasthan.

Since the Ballari tragedy, the Karnataka government too has indicated that it will adopt this model as part of an overhaul of drug safety.

Addressing the larger problem of substandard drugs would require the Indian government to enforce manufacturing standards as specified in Schedule M of the Drugs and Cosmetics Rules, Dr Dabade said.

“Drug inspectors should help companies follow protocol. Authorities should ensure that bad drugs don’t come into the market. This is not a joke. They’re playing with people’s lives,” he said.

He pointed out that enforcing standards was not impossible because Indian companies manufacturing generic medicines for export to the USA comply with US Food and Drug Administration (USFDA) standards. “These standards are higher than Indian standards, and the USFDA office monitors compliance. Why do these companies then have different manufacturing standards for medicines sold in India?”

(With inputs from Poojitha BV, Amuktha Malyada K, Ishita Malakar, Shweta Jena, Gowri Lekshmi S)

This report was republished from The News Minute as part of The News Minute-Newslaundry alliance. Read about our partnership here and become a subscriber here.

Newslaundry is a reader-supported, ad-free, independent news outlet based out of New Delhi. Support their journalism, here.