Should NASA send a mission to explore Uranus and its moons? It’s been on NASA’s “to do” list for the last decade and scientists warn that if a spacecraft doesn’t go soon the next best window will be the 2090s.

We’ll soon find out. Due on April 19, 2022 are recommendations from the Decadal Survey for Planetary Science and Astrobiology, a report compiled by the National Academy of Sciences that will set out the priorities for NASA for the next 10 years.

Although it’s expected to green-light a Mars sample-return mission—much of which is already being planned by NASA—there’s a reasonable chance that it will also instruct the space agency to investigate one of the Solar System’s “ice giant” planets, Neptune and Uranus. After all, 10 years ago a mission to Uranus was the third highest priority flagship mission. Nothing was done.

Which planet should NASA prioritise? The pros and cons of missions to the two ice giant planets can be summed-up like this:

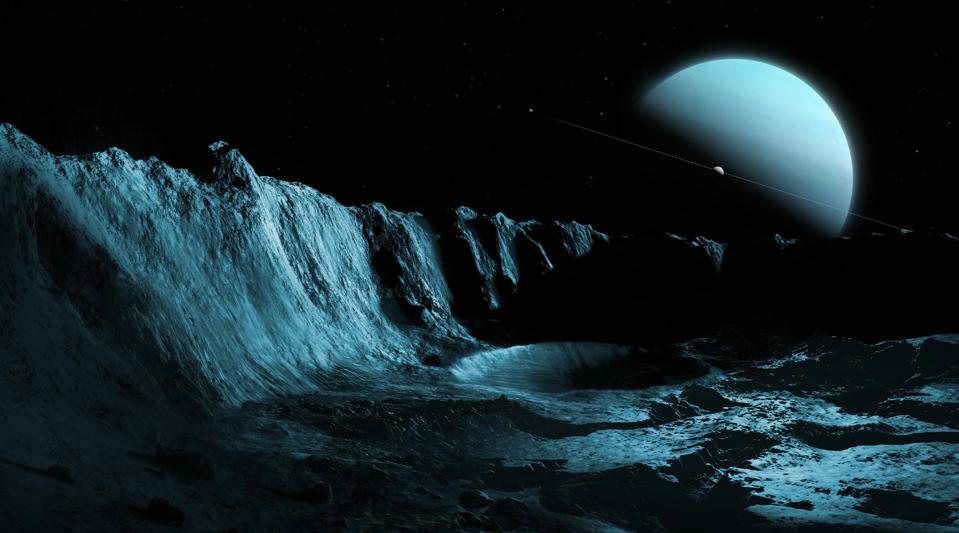

- Seventh planet Uranus has five moons that may be “ocean worlds,” which could host life.

- Eighth planet Neptune has a moon called Triton, which is believed to be a captured dwarf planet—much like Pluto—so a mission would constitute a two-for-one deal.

The case for Uranus, the third-largest planet in our Solar System on a slow 84 Earth-years orbit of the Sun, is put forward in two proposals now under review of the Decadal Survey—Quest to Uranus to Explore Solar System Theories (QUEST) and A New Frontiers Class Mission for the Uranian System.

“Uranus is the only example in our Solar System that we have of what an ice giant system would look like,” said Erin Leonard at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and lead author of the two proposals. “It’s the only place where we have moons around an ice giant that have always been there, where they’re not intruders from the Kuiper Belt then got captured, which is what Triton is.”

Leonard’s proposals are for New Frontiers missions—which cost no more than $900 million, about a third of the cost of a full-blown flagship mission—to send an orbiter to Uranus, which would launch 2032 and arrive at Uranus in 2045.

The Juno-style QUEST orbiter would investigate Uranus’ oddly-shaped and chaotic magnetic field and its extreme axial tilt (Uranus orbits on its side). Cue updates to long-standing theories of planetary formation and valuable data on ice giant-size planets, which appear to be the most abundant in our galaxy.

QUEST would also investigate why Uranus appears to be colder than it ought to be.

“What’s interesting about Uranus is that Voyager 2 detected no emission of internal heat. That’s very different from the other three giant planets, which emit more heat than they're receiving from the Sun because they’re huge compressed gas balls,” said Dr. Kunio Sayanagi at Hampton University’s School of Science. “They all have interiors with very high temperatures that slowly leaks out, but not at Uranus. There’s something interesting going on that cannot that explained.”

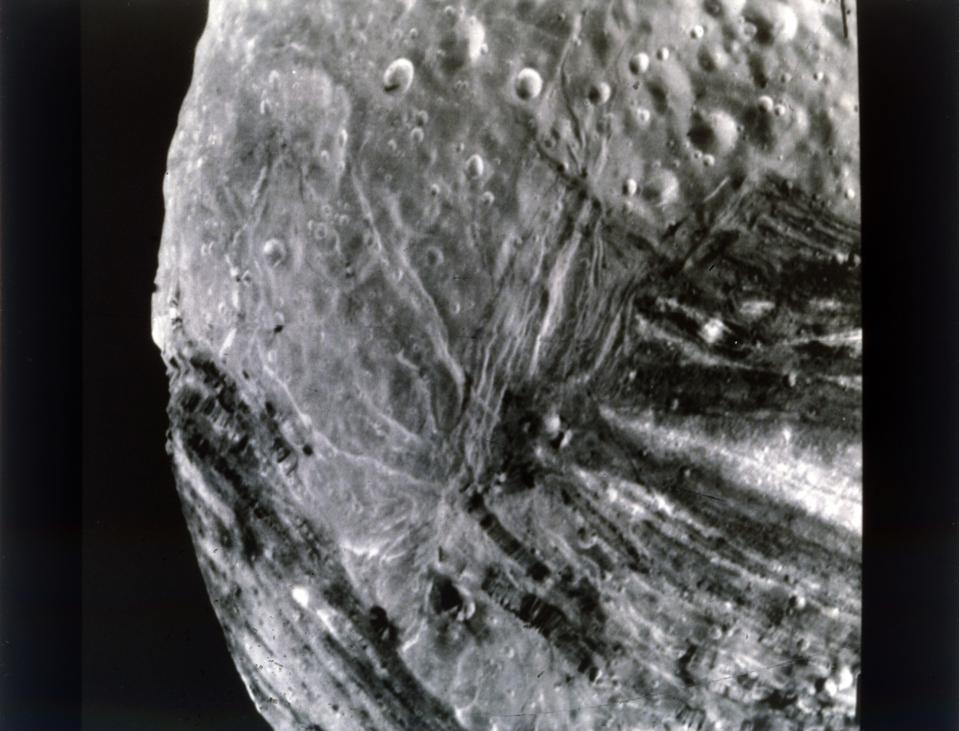

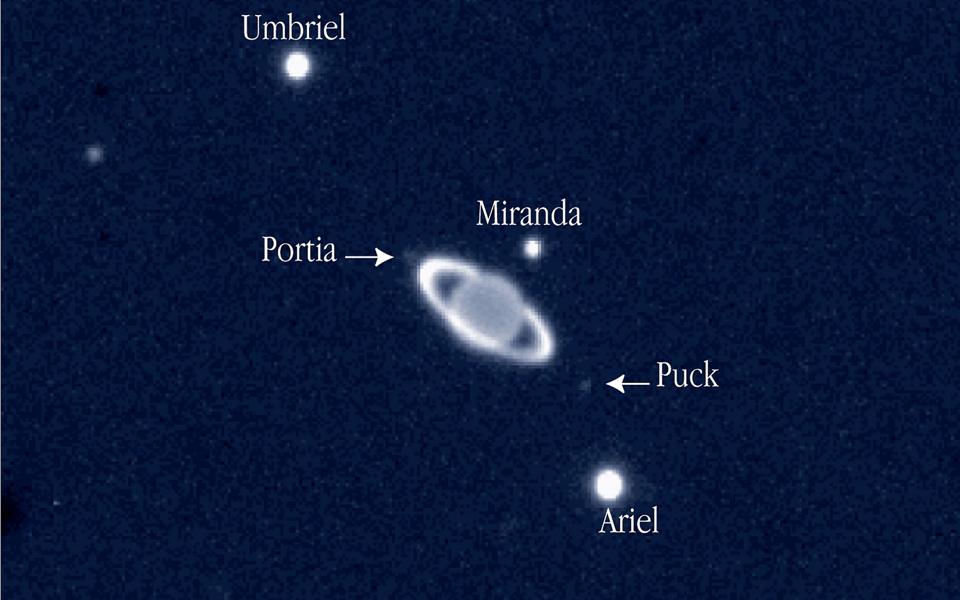

Meanwhile, the other concept focuses on Uranus’ rings, its magnetic field and an investigation—via flybys—into possible subsurface oceans on some of its 27 moons. There is tantalising evidence from Voyager 2 that the innermost and largest of the moons—Miranda, Ariel, Umbriel, Titania and Oberon—may host subsurface oceans. They also have geologically young-looming surfaces (read: free from many craters) so appear to be geologically active.

Humanity has only visited Uranus once. A short flyby on January 24, 1986 by NASA’s Voyager 2 probe gave us our only close-up images of Uranus and discovered 10 new moons. The only other images we have of Uranus are from the Hubble Space Telescope and ground-based telescopes like Keck.

Planetary scientists are desperate for a closer look at them. A “Moons of Uranus” project is already on the schedule the James Webb Space Telescope’s (JWST) very first tranche of science work later in 2022. It will spend 21 hours closely studying Ariel, Umbriel, Titania and Oberon looking for traces of ammonia, organic molecules, carbon dioxide ice and water.

Any discoveries JWST makes will inform any mission study them up close, of course, though time is of the essence. If NASA wants to send a mission a gravity-assist from Jupiter is required, something that’s only possible every 12 years or so. That will be available from 2029 through 2034.

“When the planets align correctly we can use Jupiter to get to Uranus, which means we can launch more mass and also get there a little faster, which just makes everything a little cheaper,” said Leonard.

However, there’s another seasonal reason why the time is now for a mission to Uranus. It’s critical for a mission to arrive at the Uranian system by the early 2040s when the northern high-latitudes of its moons would still be visible. This opportunity will disappear once the system goes into southern spring in the late 2040s, not returning again until the 2090s. “We don’t want it to be a whole Uranus year since Voyager was there because because the whole Uranus system is tilted on its side,” said Leonard. “When we were there with Voyager, only the southern hemispheres pf the moons were illuminated. We’d really like to see other parts of the moons.”

There are now plans for flagship and New Frontiers missions to Uranus, but whichever is the preference any such mission needs to launch between 2030 and 2032 regardless of its size or cost.

Could NASA get a mission ready in 10 years? “For a flagship mission, that’s cutting it pretty close, but you could do it,” said Leonard, citing the fact that flagship missions are inherently more complicated because they have more science instruments. “But I would say certainly for a New Frontiers mission—it’s easier to do it a little faster, but as always it all depends on the budget.”

Any mission would take 10 years to build and launch and another 13 years to get there. So either way it’s going to be a quarter of a century before anyone does any new science at the Solar System’s seventh planet.

Wishing you clear skies and wide eyes.