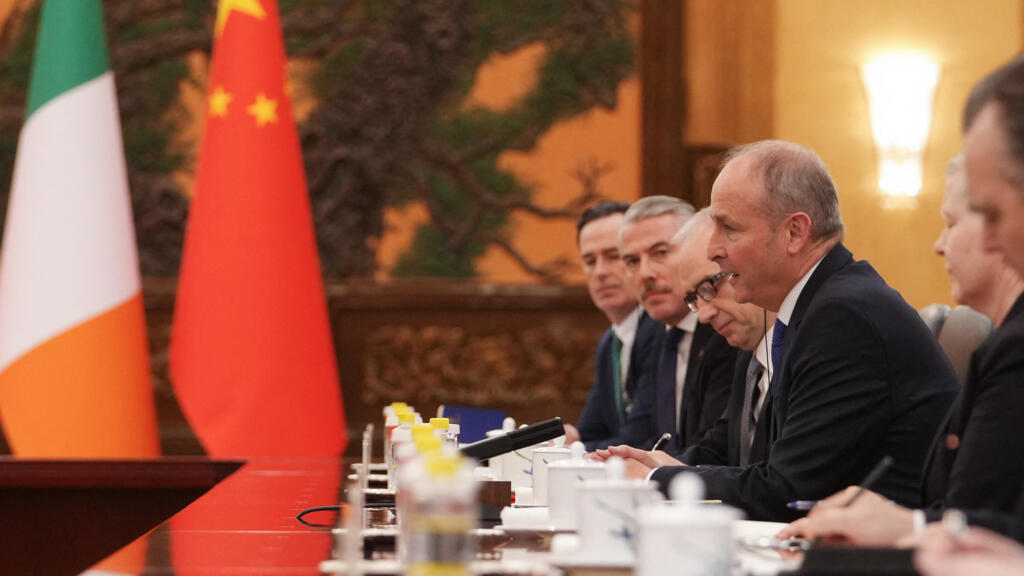

Ireland’s prime minister, Micheál Martin, arrived in Beijing this week for the first visit by an Irish leader to China in more than a decade, placing Ireland at the centre of a rapidly evolving European strategy towards the world’s second-largest economy.

The Irish leader’s five-day trip is sandwiched between Emmanuel Macron's December visit and Friedrich Merz's in February, and illustrate the fine line European leaders are taling in their approach to Beijing as transatlantic relations grow increasingly uncertain under Donald Trump's unpredictable policies.

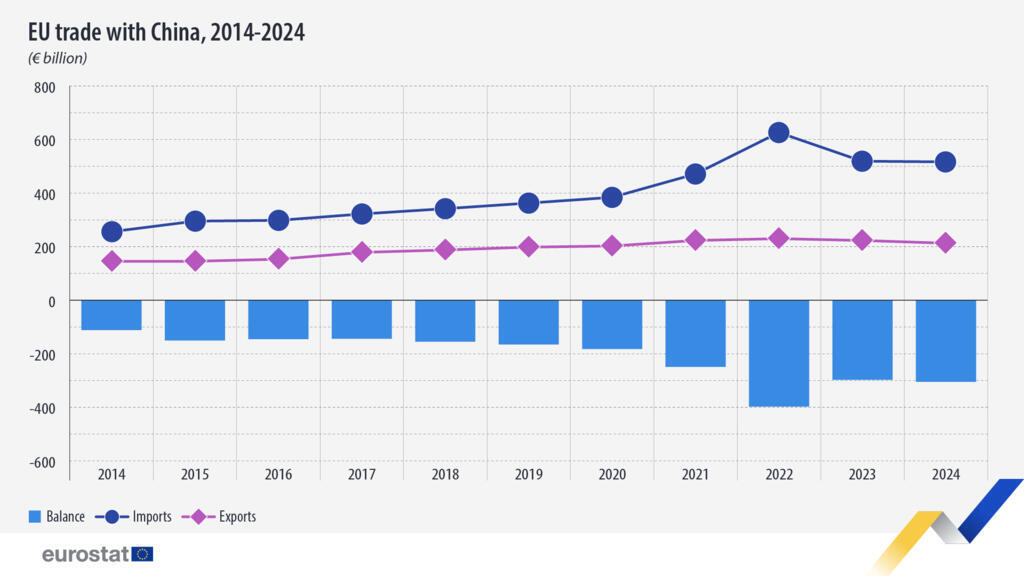

Martin's visit comes as the European Union grapples with an unprecedented €305.8 billion trade deficit with China in 2024 and mounting anxieties about economic dependencies that could prove strategically risky.

But while Brussels talks tough on "de-risking" and "strategic autonomy,” individual member states are pursuing their own pragmatic, bilateral engagement with Beijing - showing deep divisions over how Europe should position itself between an unreliable America and an assertive China.

For Macron, December's trip to Chengdu represented a continuation of his distinctive approach to China relations.

The French president, accompanied by nearly 40 chief executives, focused on securing market access for French companies whilst urging Beijing to pressure Moscow over Ukraine.

His delegation signed agreements in nuclear energy cooperation between Électricité de France and China National Nuclear Corporation, but kept on pressing Xi Jinping to address what Macron termed "global imbalances" stemming from Chinese overcapacity and export dependency.

The visit produced little concrete progress on Europe's core concerns about trade asymmetries or China's support for Russia's war machine.

The trade imbalance remains Europe's most pressing economic challenge with China. EU imports from China reached €519 billion in 2024, whilst exports totalled just €213.3 billion.

Manufactured goods - machinery, vehicles, electronics - account for nearly 97 percent of Chinese imports, flooding European markets with products often subsidised by Beijing's industrial policy.

The automotive sector exemplifies Europe's predicament: despite Brussels imposing tariffs of up to 35.3 percent on Chinese electric vehicles in October 2024, Chinese EV sales in Europe nearly doubled.

Chinese manufacturers have simply pivoted to plugin hybrids, which face no additional tariffs, while simultaneously establishing production facilities inside the EU to circumvent trade barriers altogether.

BYD is building a €4.6 billion factory in Hungary; Chery has established operations in Spain; others are negotiating sites in Italy and Poland.

How the EU’s reliance on China has exposed carmakers to trade shocks

Meanwhile, in semiconductors, China has captured approximately 30 percent of the global market for legacy chips - the mature-node semiconductors essential for automotive, medical, aerospace, and defence applications.

Whilst American export controls have largely succeeded in restricting China's access to cutting-edge chip technology, Beijing has responded by flooding the market with older-generation semiconductors at artificially depressed prices.

European chipmakers, accounting for just 13 percent of global production, find themselves squeezed between subsidised Chinese competitors and American protectionism.

The EU Chips Act aims to double Europe's semiconductor production capacity by 2030, but observers question whether the bloc can move swiftly enough to avoid dangerous dependencies.

Human rights

The human rights dimension of EU-China relations, once a consistent irritant in bilateral ties, has notably receded from prominence. Official statements still routinely express "deep concerns" about Xinjiang, Tibet, and Hong Kong, but these critiques increasingly resemble diplomatic ritual.

Human Rights Watch has criticised what it terms the EU's "failure to meaningfully address Beijing's repression," noting that the annual human rights dialogue has been demoted to a lower-level, private affair.

Trade surplus

But even without stressing human rights so as to avoid the ire of Beijing, for Ireland, navigating between Brussels, Washington, and Beijing requires particular dexterity. China is Ireland's largest trading partner in Asia and its fifth-largest globally, with bilateral trade reaching approximately $23.4 billion in 2024.

Crucially, Ireland is one of the few EU countries running a trade surplus with China - a statistical quirk largely attributable to American pharmaceutical and technology companies using Irish subsidiaries to export to Asian markets. This same arrangement makes Ireland extremely vulnerable to American policy shifts.

The Trump administration has threatened to end the tax arrangements that make Ireland attractive to American multinationals.

Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick singled out companies like Apple, Microsoft, and Pfizer for storing intellectual property in Ireland to reduce their effective corporate tax rates, stating that: “those things got to end."

Over 180,000 Irish workers are employed by American tech companies, and corporate tax receipts - overwhelmingly paid by American multinationals - accounted for over a quarter of all Irish tax revenue in 2024. The windfall from these arrangements has allowed Dublin to avoid difficult decisions about broadening its tax base.

This creates a delicate balancing act. When the European Commission proposed a digital services tax on American tech giants as potential retaliation for Trump's tariffs, Martin quickly declared Ireland would "resist that," arguing it would damage "a significant sector" in Ireland.

Dublin finds itself uncomfortably positioned: economically dependent on American companies that could relocate if pressured either by Washington or Brussels, yet increasingly recognising that diversifying trade relationships—including with China—may be prudent insurance against American unpredictability.

(With newswires)

.png?w=600)