Israel’s recent surprise attack on Iran was ostensibly aimed at neutralising Iran’s nuclear programme, but it didn’t just damage nuclear installations. It killed scientists, engineers and senior military personnel.

Meanwhile, citizens with no ties to the government or military, became “collateral damage”. For 11 days, Israel’s attacks intensified across Tehran and other major cities.

When the US joined the attack, dropping its bunker-buster bombs on sites in central Iran on June 21, it threatened to push the region closer to large-scale conflict. Israel’s calls for regime change in Iran were joined by the US president, Donald Trump, who took to social media on June 22 with the message: “if the current Iranian Regime is unable to MAKE IRAN GREAT AGAIN, why wouldn’t there be a Regime change??? MIGA!!!”

Trump’s remarks are reminders of past US interventions. The threat of regime change by the most powerful state in the world carries particular weight in Iran, where memories of foreign-imposed coups and covert operations remain vivid and painful.

Get your news from actual experts, straight to your inbox. Sign up to our daily newsletter to receive all The Conversation UK’s latest coverage of news and research, from politics and business to the arts and sciences.

In the early 1890s, Iran was rocked by a popular uprising after the shah granted a British company exclusive rights to the country’s tobacco industry. The decision was greeted with anger and in 1891 the country’s senior cleric, Grand Ayatollah Mirza Shirazi, issued a fatwa against tobacco use.

A mass boycott ensued – even the shah’s wives reportedly gave up the habit. When it became clear that the boycott was going to hold, the shah cancelled the concession in January 1892. It was a clear demonstration of people power.

This event is thought to have played a significant role in the development of the revolutionary movement that led to the Constitutional Revolution that took place between 1905 and 1911 and the establishment of a constitution and parliament in Iran.

Rise of the Pahlavis

Reza Shah, who founded the Pahlavi dynasty – which would be overthrown in the 1979 revolution and replaced by the Islamic Republic – rose to power following a British-supported coup in 1921.

During the first world war, foreign interference weakened Iran and the ruling Qajar dynasty. In 1921, with British support, army officer Reza Khan and politician Seyyed Ziaeddin Tabatabaee led a coup in Tehran. Claiming to be acting to save the monarchy, they arrested key opponents. By 1923, Reza Khan had become prime minister.

In 1925, Reza Khan unseated the Qajars and founded the Pahlavi dynasty, becoming Reza Shah Pahlavi. This was a turning point in Iran’s history, marking the start of British dominance. The shah’s authoritarian rule focused on centralisation, modernisation and secularisation. It set the stage for the factors that would that eventually lead to the 1979 Revolution.

In 1941, concerned at the close relationship Pahlavi had developed with Nazi Germany, Britain and its allies once again intervened in Iranian politics, forcing Pahlavi to abdicate. He was exiled to South Africa and his 22-year-old son, Mohammad Reza, was named shah in his place.

The 1953 coup

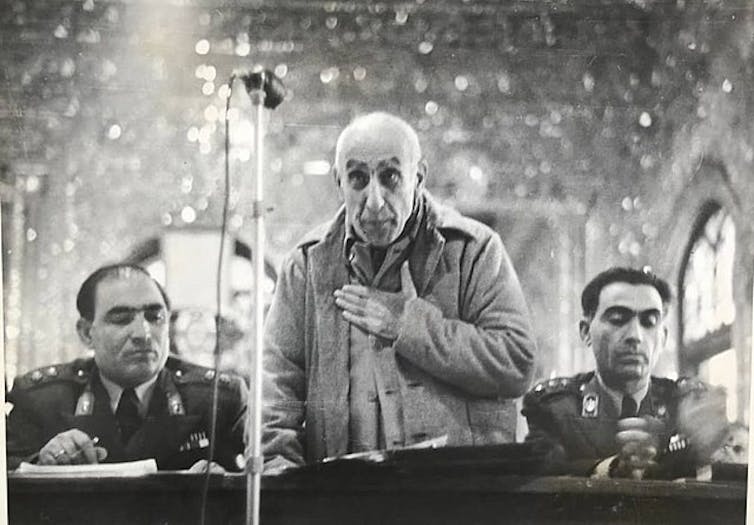

Mohammad Mosaddegh became Iran’s first democratically elected prime minister in 1951. He quickly began to introduce reforms and challenge the authority of the shah. Despite a sustained campaign of destabilisation, Mossadegh retained a high level of popular support, which he used to push through his radical programme. This included the nationalisation of Iran’s oil industry, which was effectively controlled by the Anglo-Persian Oil Company – later British Petroleum (BP).

In 1953, he was ousted in a CIA and MI6-backed coup and placed under house arrest. The shah, who had fled to Italy during the unrest, returned to power with western support.

Within a short time, Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi established an authoritarian regime that governed through repression and intimidation. He outlawed all opposition parties, and numerous activists involved in the oil nationalisation movement were either imprisoned or forced into exile.

The 1979 revolution: the oppression continues

The shah’s rule became increasingly authoritarian and was also marked by the lavish lifestyles of the ruling elite and increasing poverty of the mass of the Iranian people. Pahlavi increasingly relied on his secret police, the Bureau for Intelligence and Security of the State.

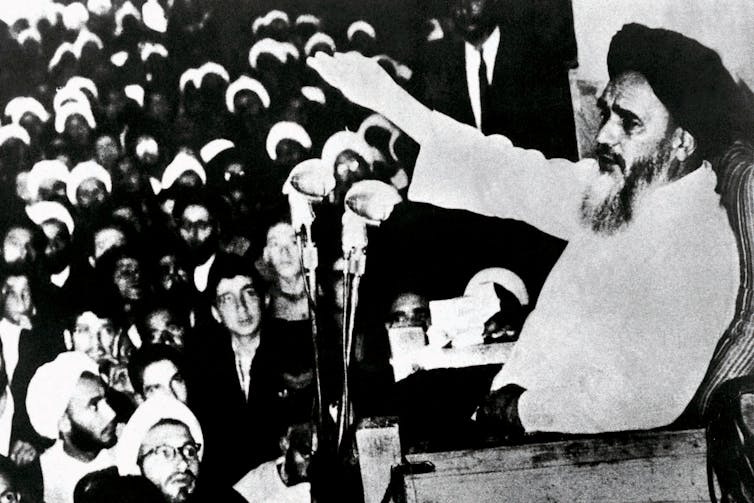

Meanwhile, a scholar and Islamic cleric named Ruhollah Khomeini, had been rising in prominence especially after 1963, when Pahlavi’s unpopular land reforms mobilised a large section of society against his rule. His growing prominence brought him into confrontation with the government and in 1964 he was sent into exile. He remained abroad, living in Turkey, Iraq and France.

By 1978 a diverse alliance primarily made up of urban working and middle-class citizens had paralysed the country. While united in their resistance to the monarchy, participants were driven by a variety of ideological beliefs, including socialism, communism, liberalism, secularism, Islamism and nationalism. The shah fled into exile on January 16 1979 and Khomeini returned to Iran, which in March became an Islamic Republic with Khomeini at its head.

But the US was not finished in its attempts to destabilise Iran. In 1980, Washington backed Saddam Hussein in initiating a brutal eight-year war, which claimed hundreds of thousands of Iranian lives and severely disrupted the country’s efforts at political and economic reconstruction.

Iran and the US have remained bitter foes. Over the years ordinary Iranians have suffered tremendously under rounds of US-imposed sanctions, which have all but destroyed the economy in recent years.

This new wave of foreign aggression has arrived at a time of significant domestic unrest within Iran. Since the Woman, Life, Freedom protests, which began in September 2022 after the death of Mahsa Amini at the hands of the morality police, there has been a general groundswell of demand for social justice and democracy.

But the convergence of external aggression and internal demands has brought national sovereignty and self-determination to the forefront, as it did during previous major struggles. While world powers gamble with Iran’s future, it is the Iranian people through their struggles and unwavering push for justice and democracy who must determine the country’s future.

Simin Fadaee does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.