On March 25, 2025, a Turkish PhD student at Tufts University, Rümeysa Öztürk, was walking in a Boston suburb when she was detained by plain-clothed federal agents. A video of the encounter went viral, sparking fear and outrage in the United States and beyond.

Since March, a growing number of international students in the U.S. have had their visas revoked or their legal status terminated for everything from engaging in political activism to minor infractions such as traffic tickets.

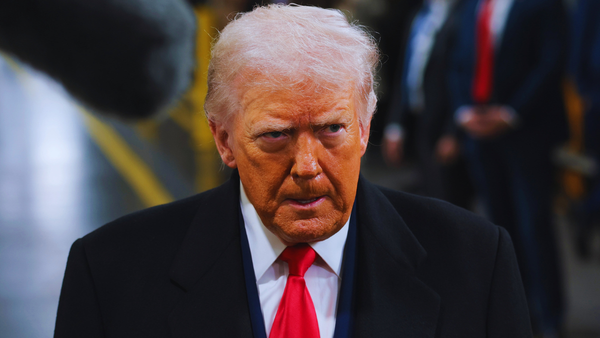

The tightening of restrictions is part of a broader effort by President Donald Trump’s administration to impose its political will on colleges and universities. These governmental interventions have caused deep concern about the future of higher education, democracy, scientific research and the rule of law in the U.S.

Read more: Three scientists speak about what it's like to have research funding cut by the Trump administration

Many of the revoked student visas were restored in late April as a result of nearly 100 federal lawsuits. But the Trump administration continues to target international students for deportation.

In Öztürk’s case, her visa was revoked for co-authoring an op-ed in a student newspaper a year earlier. The op-ed called on the university to acknowledge the plausible claim of a Palestinian genocide and divest from companies with links to Israel.

Other international students, scholars and permanent residents have also been detained for participating in pro-Palestinian protests on university campuses.

Just before the Gaza campus encampment movement arose in April 2024, we published an edited book, International Student Activism and the Politics of Higher Education. Our book brought together interdisciplinary scholars to examine how international students have engaged in political activism and advocacy through case studies.

This leads us to consider what lessons the history of international student politics might hold for addressing current challenges.

Host and home country relations

Although the backlash against international student activism has captured headlines recently, there’s a long history of international students participating in political life during their studies abroad.

These political activities have ranged from protests against tuition hikes to involvement in lobbying and demonstrations related to global geopolitical issues.

The first key lesson we have learned is that the very presence of international students on university campuses is a political matter that depends on a measure of good will between the host and home countries.

For instance, when diplomatic relations between Canada and Saudi Arabia broke down in 2018 due to a dispute over alleged Saudi human rights violations, the Saudi government ordered its students to leave Canada and study elsewhere. Despite this order, thousands of Saudi students chose to stay in Canada even after Saudi authorities withdrew government scholarships to support them.

Political courage in face of risks

A second lesson is that international student activists have often demonstrated extraordinary political courage when the risks of government retaliation are high.

After the First World War, Korean nationals studying in the U.S. took inspiration from the American Revolution to advocate for an independent Korea. At the time, participation in the independence movement was punishable by death in Japanese-occupied Korea.

Following the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989, Chinese students and scholars in the U.S. also protested against political repression in China at great risk of persecution if they returned to their home country.

Building political solidarity

A third important lesson is that the international student experience offers an opportunity for students to build political solidarity across national divisions.

The international solidarity movement for Palestine is a prime example.

During the 1960s, support for Palestine was widespread among international students of different nationalities in strongholds of student politics such as Paris. In recent years, international students have forged new alliances through the pro-Palestinian protest movement against the Gaza war on campuses around the world.

Read more: The renaming of universities and campus buildings reflects changing attitudes and values

Ebbs and flows of activism

International students have engaged in diverse forms of “front-stage” and “back-stage” political action in different contexts.

Front-stage political activism includes participation in protests, demonstrations, occupations and other political acts that are publicly visible.

Some protests are responses to specific policy changes at colleges and universities. At the University of Victoria, where we both work, international students protested tuition increases in 2019, blockading administrative buildings and occupying the Senate chambers.

Other front-stage political actions — such as the 2024 Gaza campus protests — are part of global movements.

But front-stage protests are only half the story. They often ebb and flow throughout the school year and come with significant risks due to the precarious status of international students as visa holders.

Given the heightened risks under the Trump administration, some international students are advocating for more strategic back-stage political activism to minimize public attention.

In a recent editorial, Janhavi Munde, an international student at Wesleyan University, noted that within the current political environment, “it might be smarter and safer to create change in the background” in order to “provide more scope for impactful activism — as opposed to getting arrested the day of your first on-campus protest.”

Strengthening democratic culture

The current debate over international student activism in the U.S. raises broader questions about the very purpose of higher education in democratic societies.

When asked at a news conference why Öztürk, the Turkish student at Tufts University, was detained, U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio explained that “we gave you a visa to come and study and get a degree, not to become a social activist that tears up our university campuses.”

This narrow understanding of higher education reduces the richness of the educational experience — where learning occurs both within and beyond the classroom — to a one-dimensional focus on schooling to receive a credential.

One of the main aims of higher education in democracies is to foster critical thinking and civic engagement. When international students actively participate in campus political life, this strengthens the democratic culture of higher education and society.

More than a century ago, American philosopher John Dewey observed in Democracy and Education that education is essential to striving for the democratic ideal. He argued that “democracy is more than a form of government; it is primarily a mode of associated living.” For Dewey, education could foster democracy through “the breaking down of those barriers of class, race and national territory.”

Equal dignity of all people

As geographers, we take inspiration from Russian geographer Peter Kropotkin’s classic 1885 essay where he observed that, in a:

“time of wars, of national self-conceit, of national jealousies and hatreds … geography must be — in so far as the school may do anything to counterbalance hostile influences — a means of dissipating these prejudices and of creating other feelings more worthy of humanity.”

When international students such as Öztürk urge us to “affirm the equal dignity and humanity of all people,” they are displaying political courage by embodying the ideals of freedom and democracy at a time when these founding principles of the U.S. are increasingly under threat.

Reuben Rose-Redwood has received funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Council of Canada.

CindyAnn Rose-Redwood has received funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Council of Canada.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.