Naive, self-sabotaging and riddled with Moscow’s agents, Ukraine gave up its nuclear weapons and an arms industry that produced a third of the Soviet Union’s supply, trusted the West and the Kremlin to protect it, and was left fighting for its life.

Now, 30 years on, the start-up nation redefining how war is fought has been forced into a bodge-and-make-do world of arms production, fusing old technology with IT know-how to break the bonds its allies tied to make Kyiv fight one-handed.

The latest innovation is a cruise missile with a range of 3,000km, a maximum speed of 900kmph and a payload of over a tonne, which has been used in strikes deep into Russian territory.

The FP-5 “Flamingo” missile is powered by a rocket and a Soviet-era turbofan jet engine bolted on top. Some of those engines have been dug out of landfill dumps.

It’s got twice the range of the US Tomahawk, carries twice as much explosive and costs about the same.

But its main advantage is that it is entirely under the control of Ukraine’s forces. The UK and France restricted the use of the Anglo-French Storm Shadow cruise missiles to Russian targets inside Ukraine for many months.

The US reduced the ability of Ukraine to use American ATACM missiles against Russian targets in Russia and has not yet decided on whether to allow access to Tomahawks, that would be paid for by European allies.

In contrast, Kyiv can fire the Flamingo at any target it wants. It is not restricted by what Ukraine’s “allies” say it can and cannot do when fighting Russia’s invading forces.

Prototypes were painted pink to make them easier to retrieve from test flights. They strike deep inside Russia and are designed to destroy Moscow’s capacity to wage war in Ukraine.

Targeting oil refineries has had a measurable effect. Russia has at times lost about 20 per cent of its fuel capacity and pump prices have soared by 10 per cent.

Ukraine’s focus has been on the Fluid Catalytic Cracking plants inside refineries – they’re mostly imported from the West and Russia is banned from buying any more.

With arms supplies from the West so uncertain, Volodymyr Zelensky has said Ukraine now makes about 60 per cent of its own weapons.

“When you have a gun being pointed towards your head, you don’t think about standards, you think that ‘this should be working’,” says Iyna Terech, the chief technology officer of Fire Point, which makes Flamingos among other munitions.

“And the huge achievement of the Ukrainian government is to downgrade the bureaucracy pressure as much as possible so that technology can thrive.

“And that is what happened to our company. We didn’t care that we meet Nato standards.

“We only cared that our weapons would be effective on the front line, not on some paperwork. We could, as a result, make a very effective weapon.”

As well as Flamingos, Fire Point also produces the shorter-range Shahed-style drones FP1 and FP2. The former have been used frequently to attack Russia as far as Moscow.

The latter, which carry a payload of 150kg, have been mistaken for long-range American missiles because of their explosive power.

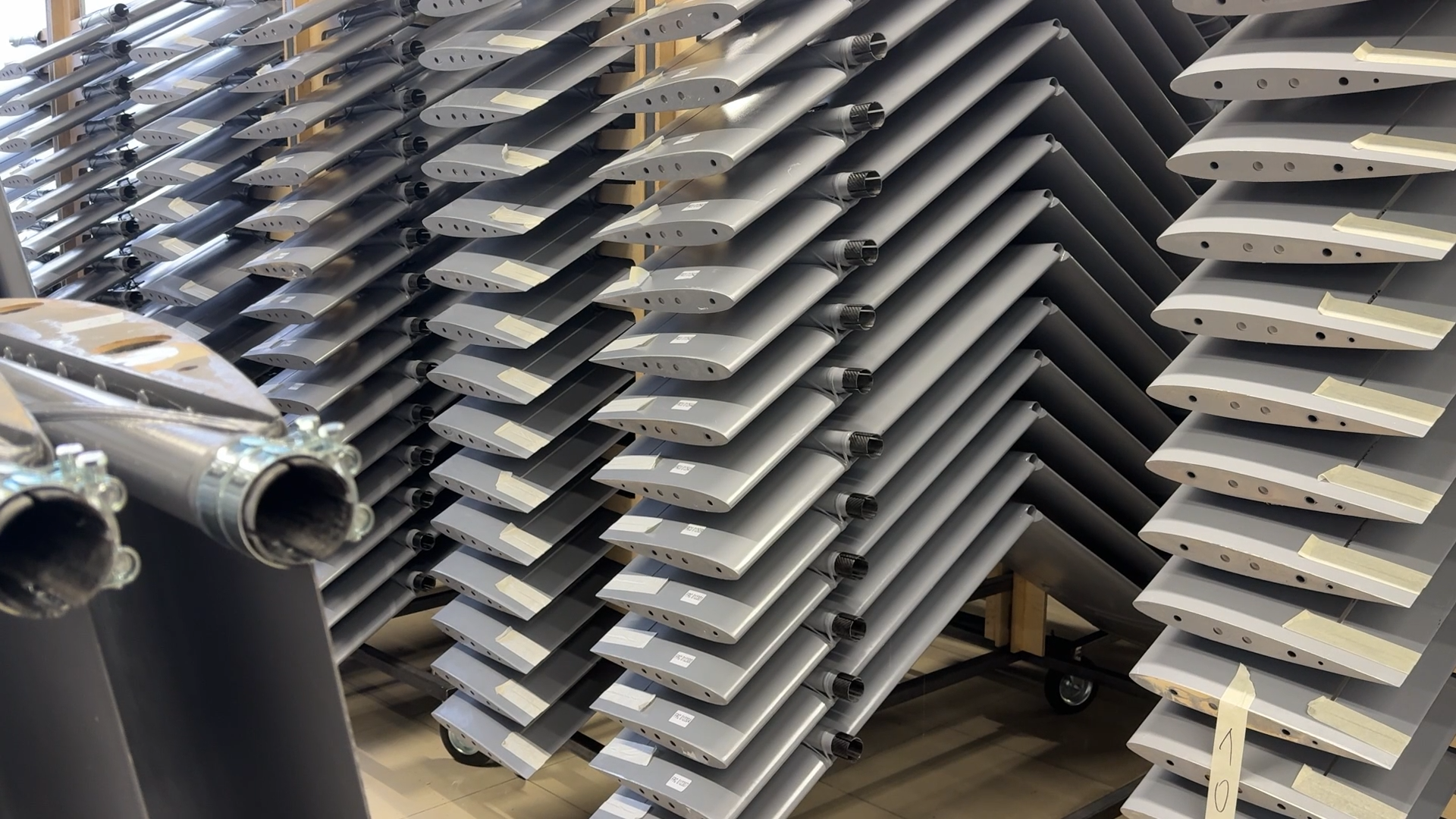

Their value lies in that they’re cheap and fast to make. It takes a couple of hours to make the wings and 30 minutes to fashion the fuselage from a mix of plastic and carbon.

The lightweight machines are glued together with carbon printers, use lawnmower engines and rely on open source navigation systems.

No money is spared, Terech insists, on the electronics of the weapons as they’re designed to evade Russian jamming systems.

Ukraine shoots down about 90 per cent of Russia’s incoming Shahed-type drones. So a similar “kill rate” of Ukrainian drones must be assumed. They have to be clever and cheap to make if they’re going to get through.

FP1s and 2s cost about $50,000 each. Ukrainian officials estimate that modern Shaheds may be as much as $250,000 each. Independent estimates put the Russian-made drones at closer to $80,000.

For Ukraine, price competition is important. The European Union, Kyiv biggest backer, is an economic bloc at least nine times the size of Russia’s economy with four times its spending power.

Ukraine’s allies can outspend Russia, if they choose to, but so far they have not.

The war is now mostly a grinding stalemate. It balances Russia’s superior manpower resources with Ukraine’s motivation and innovation, although that latter edge risks being eroded as Moscow has moved quickly to learn from earlier bloody mistakes on the battlefield.

Russia has had years to prepare for its invasion of Ukraine. With hindsight, it was aided by the collapse of Ukraine’s arms industry after its independence from the Soviet Union in 1991.

Back then, Ukraine had the third-largest nuclear weapons stockpile. It produced 30 per cent of the Soviet Union’s weapons.

Ukraine produced some of the Kremlin’s most terrifying weapons –intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) like the SS-18 “Satan”.

Kyiv still has a factory where the company Antonov made many of its aircraft, and the capital was also the centre of production for anti-tank and anti-aircraft missiles.

Kharkiv in eastern Ukraine produced tanks and boasted 40 universities and educational institutions, which churned out scientists who made rockets for sale worldwide.

But in 1994, Ukraine was persuaded to give up its nukes in return for an agreement from the US, UK, and Russia to guarantee its security.

Later, China and France signed up, but only Ukraine believed the memos were worth the ink spent on setting them down.

Ten years later, it had let its arms industry collapse from one that employed three million to less than a third of that.

A mouldy military faced Russia’s first invasion in 2014, and the country was saved mostly by private volunteer militia.

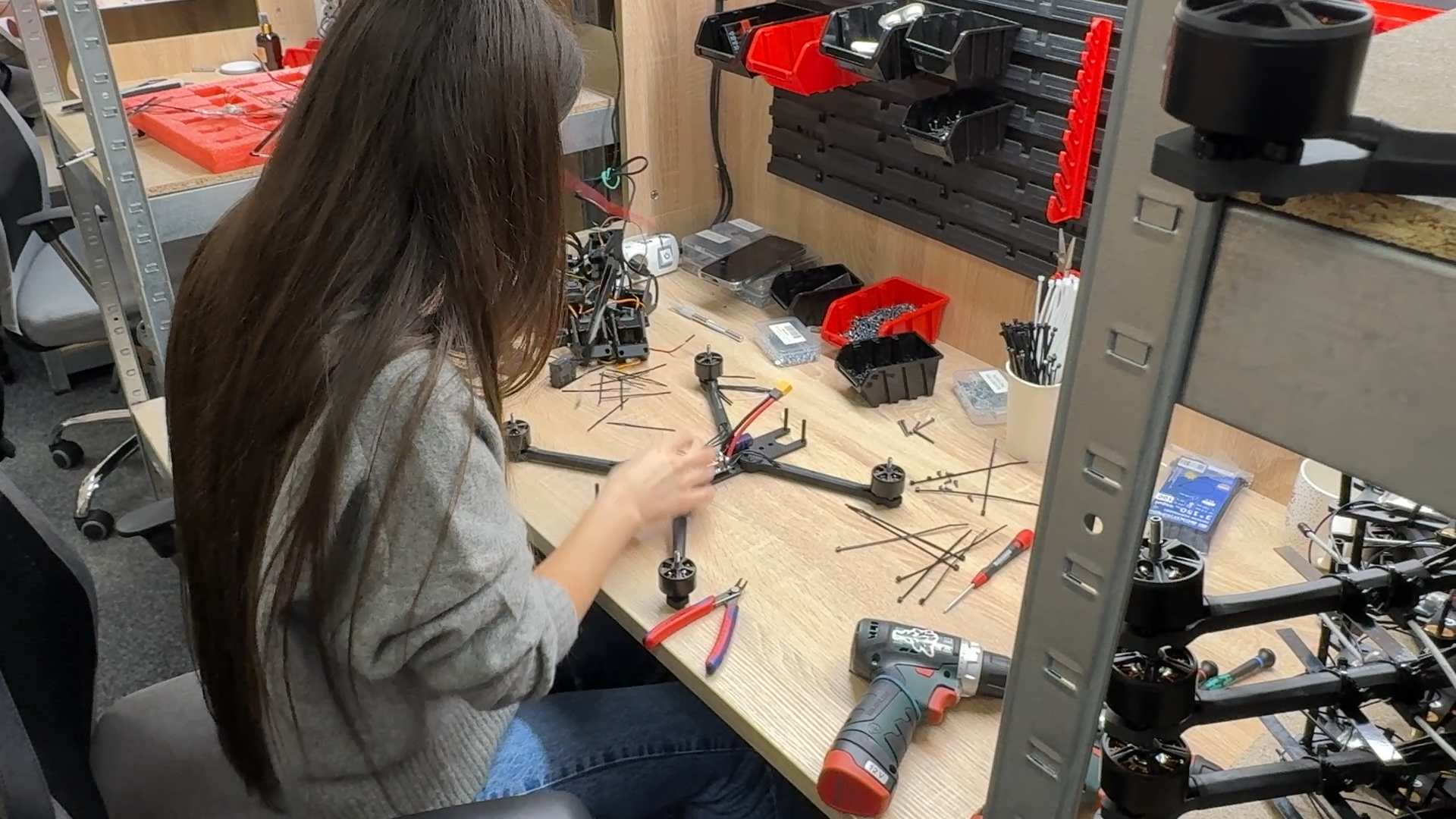

Now it is reliant on start-ups like companies such as Fire Point and General Cherry – the latter producing thousands of interceptor drones a week to take on Russia’s Shaheds and protect troops on the front lines, where combat has turned from trench warfare to a churning horror for infantry individually hunted by tiny deadly drones.

In production, 3-D printers whir day and night in secret locations across Ukraine. In cubicles across the nation, drills scream and solder burns and circuits are laid for semi-autonomous quadcopters to be flown into incoming missiles every night.

Ukraine’s weapons industry is now worth only $1bn, but it is growing very fast. Taking off like one of the Ukrainian GC’s “bullet” drones, which erupt from the ground and can hit over 200kmph in a vertical climb to take on Russian Shaheds.

Midway through what is a long war, there’s an air of growing confidence in Ukraine’s arms industry.

It’s bred off fast growth and battlefield success.

But also the realisation that, already, Ukraine has the most powerful army in western Europe and that the lessons learned from battleground to workshop here will mean Kyiv may be a dominant force in Europe’s future.

“We all have to grow up and build our own security with our own hands,” says Terech.

This means ending reliance on America.

”What we learn from working in Ukraine is that you have to diversify and you have to rely on yourself. You have to count on your own resources, and that’s what Europe has to do.”