In the novels of John le Carré, the term “tradecraft” is a shorthand for the techniques of covert intelligence gathering: the “dead drops” used to pass messages from spy to spy, the surveillance devices that might bug an apparently unassuming hotel room, and complex networks of fake identities and misleading counter-narratives designed to destabilise the enemy. These insights into the shadowy world of espionage, with their push-pull of concealing and revealing are part of the enduring appeal of le Carré’s work, rendered all the more alluring and authentic thanks to his own half-decade stint in the secret service.

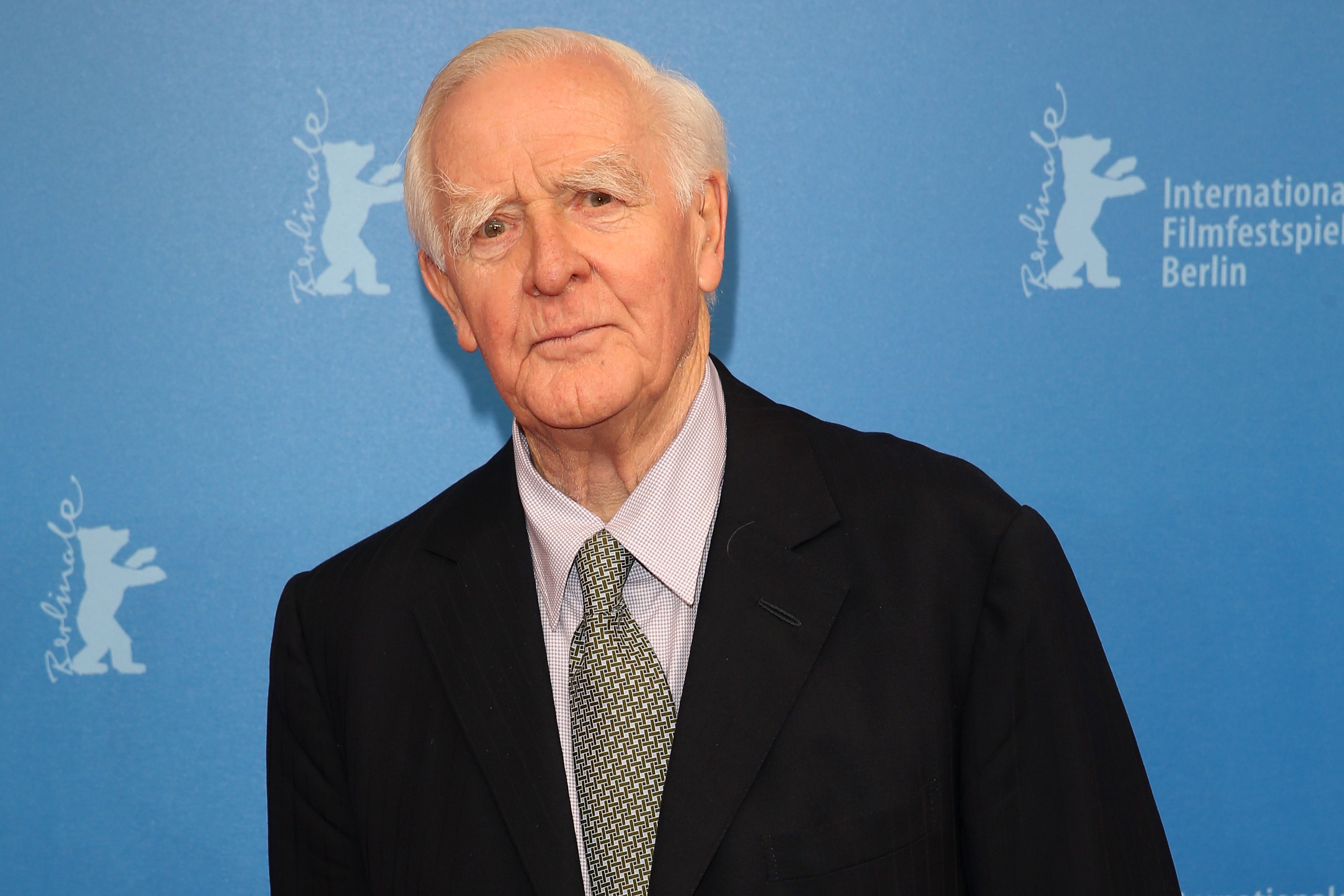

But his own “tradecraft” as a writer was just as intriguing. Five years after the author’s death at the age of 89, and 15 years since he started the process of handing over his vast archive to the University of Oxford’s Bodleian Library, a new exhibition is shedding light on the fascinating, often idiosyncratic creative process behind novels such as Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, The Night Manager and The Constant Gardener. “John le Carré: Tradecraft” draws from the 1,200 boxes of material in that archive, which have never previously been displayed publicly, to explore the meticulous working methods of the author (real name David Cornwell).

For le Carré, research was everything; his fictional scenarios, he believed, needed to take place against entirely believable backdrops, if he was going to convincingly grapple with real-life conflicts and issues. “One thing that comes through in the archives of his research is his obsession with authenticity and credibility,” says the exhibition’s co-curator, the historian Dr Jessica Douthwaite. “He was always [engaged in] creative writing. It was always fiction. But all of this research was going towards his real desire for there not to be one factual error in his creative writing. He wanted it to be so authentic that it would capture the imaginations of people.”

To achieve this, he resorted to spy-like methodology, recruiting a network of informers (well, experts) who could provide him with the sort of on-the-ground knowledge that would be hard to glean from books and reports. Those collaborators might be authors, foreign correspondents, lawyers or charity workers; among their number was Professor Federico Varese, co-curator of the exhibition and editor of the accompanying book, and a longtime friend of le Carré. Back in the early Nineties, when Varese was carrying out fieldwork for his dissertation on the Russian mafia, he received a letter from the author, which had been forwarded from his Oxford college. Le Carré (who signed off with his famous pseudonym but added his real name in brackets below) asked whether the young academic would be willing to discuss his next novel, later published as Our Game, “which touches upon the Ossetian-Ingush conflict” that had escalated in Russia just a few years earlier.

Varese agreed, starting off a collaboration and friendship that would last for decades. No detail was too small to corroborate. “I remember working on a novel with him, and there was a scene about a funeral in Moscow at a certain time of the year,” Varese says. “And he wanted to make sure that the trees that he would be describing were actually in that very cemetery. Or it might be the brand of cigarettes that the character was smoking. He was really obsessed with details.”

All of this would be documented in spidery handwriting in tiny notebooks. “David [le Carré] had hundreds, no, thousands of notebooks, and he started [his novels] in a notebook as big as his hand,” the academic adds. Often, these jottings would be sprawling, lacking in any discernible order, although the exhibition does feature one rare example of more disciplined note taking, for The Mission Song, where the writer has chronicled the novel’s premise on one side of the paper, and written details of the “research needed” on the other. “I actually haven’t found another example of his being as organised as that,” Varese says. “So it’s nice to see it so succinct.”

Le Carré didn’t just rely on the accounts of others, though. From the Seventies onwards, he would make sure to visit the places that he wrote about, a part of his process spurred on by one factual error that was particularly galling (to him, at least). In 1974, the writer was visiting Hong Kong, when his trip was interrupted by an unwelcome discovery. An underground tunnel now existed between the island and mainland China – meaning that a scene in the about-to-be-published Tinker, Tailor, in which his characters made this journey by ferry, had been rendered outdated. “To my everlasting shame I had dared to write the passage here in Cornwall with the help of an outdated guidebook,” le Carré recalled in his 2016 memoir The Pigeon Tunnel. “Now I was paying the price.”

It’s the sort of irritating but far from catastrophic mistake that another author might have sighed over then moved on. Le Carré, though, was not that kind of writer: he called up his agent to find out whether he’d missed the deadline to amend the passage, drove through the tunnel a few times, faxed a revised version back to the UK and “swore I would never again set a scene in a place I hadn’t visited”. In the end, Varese says, it was “too late”, and the first editions were released with the erroneous scene. “That was seen as a turning point by his family,” he adds, and “from that moment on, he travelled to every single location”, from Lebanon (for The Little Drummer Girl) to Rwanda and eastern Congo (for The Mission Song).

All of this research was going towards his real desire for there not to be one factual error in his creative writing

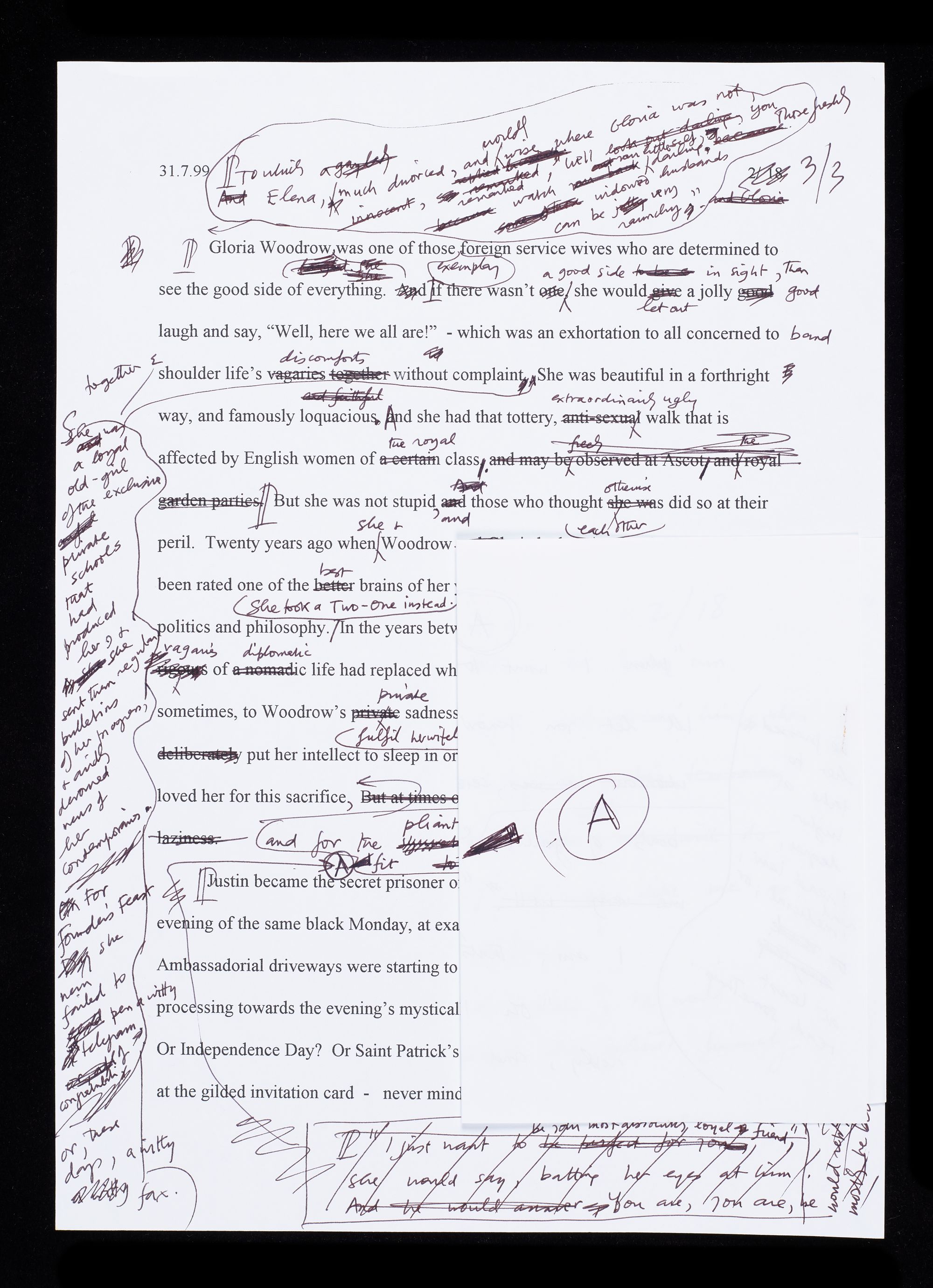

Once the research was complete, the painstaking process of drafting would begin. “Le Carré only ever hand-wrote things, and then his wife [Jane Cornwell] typed them up,” explains Douthwaite (for the earlier books, written before the advent of the word processor, she would’ve used a typewriter). He’d then cut up those typed drafts to move around sentences and paragraphs: “He would stick them, sellotape them, staple them, move them around, and then he would rewrite them by hand and Jane would type things up again.” This relationship is something that the curators wanted to do justice to (it’s certainly an interesting counterbalance to all the attention heaped upon le Carré’s infidelities in the wake of his death). The couple, Douthwaite adds, seemed to share a secret language, with Jane somehow managing to parse her husband’s dense arrows, symbols and annotations. “Honestly, I’m amazed that she did understand his process,” she says. “Sometimes it's really quite astonishing that she made anything more of his annotations.” One typewritten page from The Constant Gardener featured in the exhibition is all but obliterated by black ink scrawls, and includes an extra, stapled-on page full of additions.

On the page, le Carré’s prose feels meticulously crafted, so it is perhaps no surprise that his sentences emerged gradually, like a sculpture emerging from a block of granite. For devotees, there is something very special in laying eyes on the pink sheet of paper on which the author drafted out an early iteration of his famous introductory description of his best-loved character George Smiley, the “small, podgy and at best middle-aged” agent, in Tinker, Tailor, hurrying through the London rain, “his gait anything but agile”. Detailed research may have provided a bedrock for le Carré’s stories, but it’s his way of getting to the heart of a person with just a few illuminating phrases that make reading him such a joy.

Perhaps that is why the curators are keen for this exhibition to turn around the public perception of le Carré as a secret agent who ended up turning to fiction, to instead present him as a writer who just happened to spend a few years doing intelligence work. “He was not a spy who wrote novels, he was an artist, a novelist, a writer, who briefly worked in the secret service,” Varese says. “For him, the spy world was an inspiration to address what I would consider universal problems in human life: trust, betrayal and love.”

John le Carré: Tradecraft is at the Weston Library, part of the Bodleian Library, until 6 April 2026.