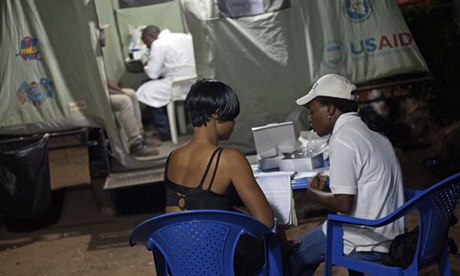

It was almost midnight in Lubumbashi, and as we walked up the street, the sound of Congolese dance music mixed with the clink of beer bottles. I was visiting PATH's innovative night-time outreach program, which offers HIV counseling, testing, and referrals to some of the people most at risk of infection—including truckers, sex workers, and men who have sex with men—at an urban hot spot known as Kamolondo.

These nighttime HIV services provide a more convenient and anonymous way for at-risk people to be tested and, if HIV-positive, to be referred to services. I saw firsthand the powerful social dynamic between people who come to the testing site and trained educators, who encourage their peers to be tested, wait for the results with them, and then support each other, whatever the outcome.

The courage to be tested for HIV

I met Judith, a 19-year-old sex worker who was very afraid of getting an HIV test because she had slept with an HIV-positive partner. She was terrified that her test result would be positive.

I watched as Judith's friends convinced her to join the more than 200 people who came to be tested that evening. She closed her eyes tightly during the blood draw, but when she heard that her test was negative, Judith beamed, hugged her friends and me, and waved the test result in the air.

"I was very afraid," Judith told me. "I had four sexual encounters with a client who died from AIDS. Fortunately for me, I was lucky and I am not infected."

Having a site like this in the middle of a party scene calls attention to the HIV epidemic, educates those most at risk of infection, and reduces the stigma that getting tested for the virus often carries.

Support where it's needed

Later that night I met a group of peer educators from PATH's champion communities program who told me about their critical HIV prevention and treatment work. They were doing peer outreach with sex workers and men who have sex with men—navigating bars, brothels, and other social hot spots to support the well-being of others, engage peers in fighting Aids, and encourage testing.

The champion community approach uses peers to organise, assess, plan, implement, and monitor community response to the epidemic. To date, these efforts have reached more than a million people.

Joel Welo, the president of the champion community I visited that night, told me, "The champion community approach is helping us protect our community."

Big challenges require innovative solutions

No one argues about the scale of the health burden in DRC. The United Nations' least developed countries report 2013, released in November, again lists the country as one of the most underdeveloped in the world, and I saw myself its needs, challenges, and vast size.

I spent time discussing the depth and complexity of the problems with a range of Congolese: truck drivers, clinicians, sex workers, peer educators, leaders of nongovernmental organisations, and the country's minister of health.

I also saw that programs can be successful as the country stabilises and rebuilds after years of war. I witnessed results-driven, innovative programs that tackle a variety of health issues, from HIV to tuberculosis to family planning. An example is our remarkable public-private partnership with Tenke Fungurume Mining to strengthen health in the region surrounding the largest copper mine in DRC.

Again and again, I saw programs like this that bring together the best thinking, leadership, and capacities from industry, nongovernmental organisations, and government to reach underserved people in novel and effective ways.

More information

• Our work in the Democratic Republic of Congo

• Life with dignity, and HIV/AIDS

• Data that can help fight HIV

• Integrated HIV/AIDS Delivery in the Democratic Republic of Congo (ProVIC) on the US Agency for International Development's website

• Least Developed Countries Report 2013 on the United Nations website

Follow Steve Davis on Twitter @SteveDavisPATH.

This piece originally appeared on the PATH blog

All content on this page is produced and controlled by PATH