A lawmaker in India is demanding an end to climbing on the world's third-tallest mountain.

The Chief Minister of India's Sikkim region wants climbers to steer clear of the 28,169ft (8,586m) Kangchenjunga mountain out of respect for local deities.

The towering mountain lies partly in Sikkim and partly in Nepal, and is climbed by around 30 to 50 expert mountaineers each year. It hasn't been scaled from Sikkim since the only Indian route permanently closed in 2000. Now, Minister Prem Singh Tamang wants to ban climbing from all routes, including those in Nepal.

In a letter addressed to India's Home Minister, Tamang said: "Scaling this sacred peak is not only a matter of serious concern but also a violation of both the prevailing legal provisions and the deeply held religious beliefs of the people of Sikkim."

His demand is based on India's 1991 Places of Worship Act, which forbids climbing on sacred sites.

Kangchenjunga is of great religious significance to people in both Sikkim and Nepal. In legend, the mountain is home to the Dzo-nga, a yeti-like deity who lives atop the peak. Other beliefs point to the existence of a valley of immortality hidden among its slopes.

Tamang's calls for a ban follow an ascent by Indian climbers from the National Institute of Mountaineering and Adventure Sports of Arunachal Pradesh in May. The five climbers scaled the mountain via the legal Nepalese route and were assisted by several Nepali guides.

Multiple other Indian climbers also summited the mountain last month, including members of a joint Indian-Nepali army expedition.

Conditions on the mountain have been unforgiving this year, prompting multiple rescues and the death of a French climber in mid-May. Margareta Morin, 63, fell ill as she pushed for the summit and died at 25,591ft (7,800m).

One of the icons of the Himalayas

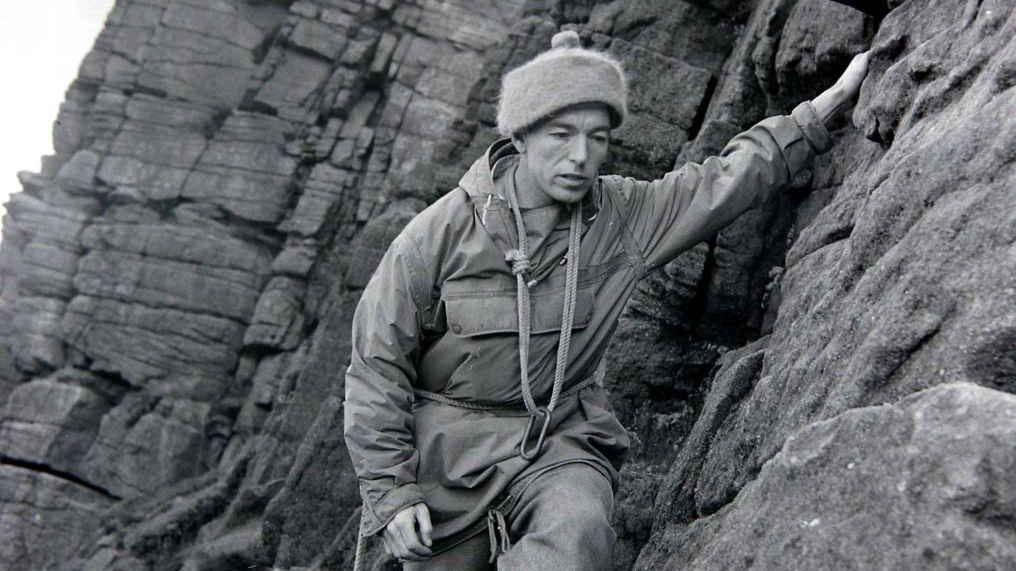

Despite not receiving the sort of public interest that Everest gets, nor even the world's second highest mountain, K2 – Kanchenjunga has long been an icon of the Himalayas. Thought to be the highest of them all until the mid 19th century, it has long been a draw for mountaineering's elite. The prize of the first ascent was claimed in 1955 by Joe Brown and George Band, two of Britain's greatest ever climbers and mountaineers.

This remarkable ascent is considered by some to be an even greater achievement than the first ascent of Everest two years earlier by Tenzing Norgay and Edmund Hillary. Notably, Brown and Band purposefully stopped around five feet short of the true summit in a show of respect to the Sikkim authorities and the wishes of the local people.

It would be 18 years before the next attempt on the summit and 22 years before the second ascent of the main peak. The first ascent without supplementary oxygen was made by British trio Doug Scott, Peter Boardman and Joe Tasker in 1979. The latter two died on Everest's North East Ridge in 1982, while Doug Scott would go on to be awarded the Walter Bonatti lifetime achievement award at the Piolets d'Or ceremony in 2011, putting his name alongside the likes of Reinhold Messner and Chris Bonington, as well as American greats John Roskelley, Jeff Lowe and George Lowe.

Sacred summits

Many peaks in the Himalayas are held sacred and many of the world's greatest unclimbed mountains are also untrodden for this very reason. This includes the iconic fishtail summit of Machapuchare in Nepal, which holds special spiritual significance to the local believe who believe it is the abode of the god Shiva.

Even Everest, whose much-sought-after summit sees many mountaineering boots every year, is sacred. Its Tibetan name is Chomolungma, which means Goddess Mother of the World. It's Nepalese name is Sagarmatha, which has various meanings.

The name Everest was given to it in the 19th century, inspired by Sir George Everest (properly pronounced Eev-rest), a former Surveyor General of India, who was actually opposed to the naming himself.

- The best ice axes: for tackling frozen terrain

- The best snowshoes: for cold-play adventures all winter long