India’s Supreme Court has backtracked on a controversial order that all stray dogs in Delhi must be rounded up and placed in shelters, after an outcry from animal welfare groups, politicians and citizens who warned it was neither humane nor feasible.

Earlier this month, the court ruled that every stray in the capital region – close to 1 million dogs, according to estimates – should be removed from the streets within eight weeks. The directive followed rising reports of dog bites and rabies cases nationwide, and a media storm over the death of a child allegedly from rabies.

Yet Delhi has barely 20 shelters and sterilisation centres, and many of these have capacity for only a few dozen animals. A larger facility visited by The Independent this week was crowded with ill and traumatised animals, many of which had visible open wounds. Even if more such shelters are built, activists say, housing dogs permanently in cages would cause immense suffering, spread disease, and ultimately fail to control the street population.

Under intense pressure and following a heated, weeks-long national debate on the issue, the court abruptly revised its order on Friday, saying that dogs should be captured and released back to the streets they live on after being sterilised and vaccinated – which is largely in keeping with current best practice.

But a line in the new order – that dogs considered “aggressive” or potentially rabid should not be released – is poorly defined, leaving a legal loophole that campaigners worry could be used as a licence for animal abuse.

Former federal minister Maneka Gandhi, one of India’s most prominent animal rights advocates, cautiously welcomed the modified order, calling it a “scientific decision”. But many experts say the episode has exposed a deeper malaise in how India manages its street dogs – a mixture of municipal neglect, poor enforcement of existing laws, and public misunderstanding.

‘Disbelief’ at the court’s order

For Ambika Shukla, a veteran animal rights campaigner in Delhi, the Supreme Court’s initial directive was “unbelievable”.

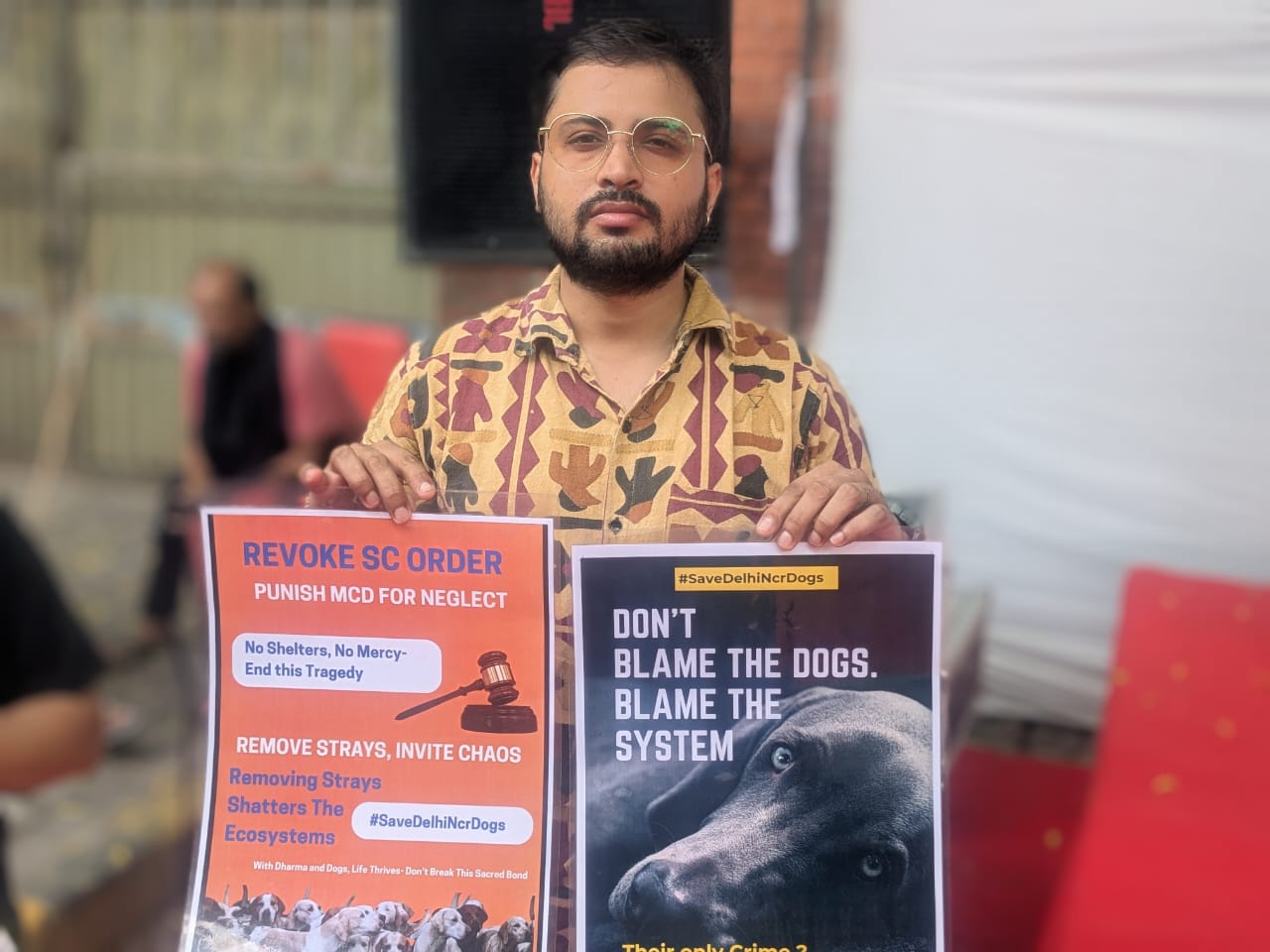

“It is not conceivable that the Supreme Court would pass an order without due deliberation, without consideration of the scientific facts, evidence on the ground, and the availability of resources,” she told The Independent while taking part in a protest at Jantar Mantar in central Delhi earlier this week. “For a Supreme Court to react with emotion and anger rather than evidence and science is truly unbelievable. I didn’t believe it at first.”

The proposal that all street dogs be confined to shelters struck animal welfare groups as not only logistically impossible but also ethically wrong.

“When you house dogs in shelters, what are shelters? They are jails for animals,” Shukla says. “These are neglected places where animals are taken simply for treatment and recovery, and they are released as quickly as possible because everybody realises that no animal is happy in captivity. To keep an entire species in jail because of some bites – it makes no sense.”

Activists’ concerns over the state of these shelters are not unfounded. The Independent arrived to a pungent smell of decay on a visit to a dog shelter run by a charitable trust in west Delhi that houses around 300 to 400 injured, abused or abandoned dogs along with those recently sterilised and neutered.

Despite Delhi’s sweltering August heat and humidity, only some parts of the shelter are shaded from the 3pm sun, with a group of injured dogs and puppies crowded together near an air cooler that isn’t working. Hundreds of animals in various states of ill health lie baking in the open area. The stench from this part of the shelter is overwhelming.

Some of the dogs have gaping wounds. Those with the worst injuries, and those who have just had sterilisation surgery, are kept in a separate area for recovery. Here a grey pit bull – not a typical Delhi street-dog breed – is kept on its own in a 6ft pen, lying on one side and not moving.

A deep cut on his foot is infested with maggots. “He was left outside the shelter gates about two days ago with the injury,” Pradeep, a compound caretaker, tells The Independent. “He has not moved or eaten since we took him in. We do not know why the owner abandoned him, but I suppose it was because of the foot injury.”

Most of the dogs here have either been abused over time or severely injured in accidents or dog fights, explains Pradeep. While they are sometimes left by owners who then pick them up a few days later, many are simply abandoned outside the gate.

“We then take care of them for ever,” says Pradeep. “But when a dog’s owner drops them at the shelter, they sometimes just stop eating. They do not want anything but their master. They won’t eat the tastiest food, the biggest pieces of chicken. Who will tell them no one is coming for them?”

Shelters also pose public health risks. Confined dogs, especially when crowded, are prone to infections, stress, poor nutrition and premature death. “Dogs enjoy human company just as much as humans enjoy theirs,” Shukla says. “To deprive both communities of this interaction is senseless. Dogs have lived alongside us for centuries.”

India has 52.5 million stray dogs nationwide, according to a 2021 survey by Mars Petcare. Around 8 million live in shelters, which are often overcrowded and underfunded. In Delhi alone, according to media reports, there are thought to be nearly a million dogs. The city’s existing sterilisation centres together hold barely a thousand at a time.

The humane alternative – sterilisation and vaccination

At the core of India’s legal framework on stray dogs is the Animal Birth Control (ABC) programme, first introduced in 2001 and updated in 2023 under the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act 1960. It requires stray dogs to be caught humanely, sterilised, vaccinated (especially against rabies), and then released back to the exact location they were picked up from. This avoids territorial conflict and keeps the numbers stable.

The World Health Organisation endorses sterilisation and vaccination as the only sustainable way to reduce rabies and dog bites. Bhutan, India’s much smaller neighbour, has achieved near-total sterilisation and vaccination of its strays after a 14-year-long campaign that began in 2009 and concluded in 2023.

Campaigners argue that India, with its broader veterinary infrastructure, could do the same if the programme were properly implemented.

“The rules are more than adequate, but they have never been implemented strictly by the authorities,” Geeta Seshamani, co-founder of Wildlife SOS and vice-president of Friendicoes, one of Delhi’s largest animal welfare organisations, told Print.in.

‘Failures’ of the municipal authorities

Delhi’s municipal corporation (MCD) has been sharply criticised for failing to enforce the ABC programme. Justice Vikram Nath of the Supreme Court said during the hearings: “This is happening because of the inaction of the municipal corporation. The government does nothing. The local authorities do nothing.”

Shukla agrees. “MCD has failed on all fronts – in training its staff, in motivating them, in implementation, in accountability. Working in the dog squad is considered a punishment posting. These are people with no training, no inclination, no understanding of why their job matters. How can they succeed?”

All Creatures Great and Small (ACGS) volunteer and advocate Divyam Khera lashes out at the MCD for its poor efforts in respect of the sterilisation drive, saying that if it had actually done its job “there would be no dogs on the streets today”.

“The existing ABC [centres], most them are in a horrific condition, where the standard operating procedures (SOPs) are not followed. Dogs come back with stitches open,” he tells The Independent as he raises concerns about inadequate funding.

“The laws, rules and SOPs are there, but they are not being followed. Had they been followed, the situation would have never arisen,” says Khera. “Why should dogs suffer because of [our] systematic failure?”

The Independent has contacted the MCD for comment.

Even when NGOs step in, a lack of funding remains the major obstacle.

Shiv Kumar, 45, a caretaker at Sonadi Charitable Trust, Delhi’s largest ABC centre, says the government pays only 1,000 rupees (£9.40) per sterilisation – far less than the actual cost of 1,500 rupees, with payments also pending. The NGO relies primarily on public donations to do the work.

Kumar expresses concern that the municipal authorities only seem to act on the issue of stray dogs when Delhi is hosting high-visibility events, such as the G20 summit last year, and in the run-up to annual Independence Day parades. And even then, the way dogs are rounded up in vans is deeply controversial, with accusations that they are simply dumped outside the city’s confines.

“Since the court order, we have not sent our vans to pick up the dogs,” he says, expressing his own displeasure at the earlier decision by the Supreme Court.

Community feeding of strays is another flashpoint. The Supreme Court has now directed that designated feeding zones be established, but activists say this is already part of the ABC rules.

In New Rajendra Nagar, a Delhi neighbourhood, residents’ associations have worked with dog feeders to create dispersed feeding points.

“The feeders chose the locations responsibly – spread out, so dogs don’t gather in packs, and at night when children and older people aren’t around. The result? No increase in numbers, no puppies, no bites, no rabies in three years,” Shukla says.

Legal experts warn that the Supreme Court’s modified order still leaves dangerous gaps. The undefined category of “aggressive dogs” could legitimise arbitrary killings or indefinite confinement.

Corruption is another persistent issue. Shukla alleges that some MCD-funded centres are run by retiring officials who view them as a source of income.

“If you sterilise 10 dogs and show 100 in your records, you get paid for 100. There is no accountability. Mortality is not even recorded. Every life is important, but if a dog dies in surgery, it isn’t reported. That would never be acceptable in human hospitals.”

She argues that the solution is to entrust the programme to committed animal welfare groups rather than uninterested municipal departments. “No animal welfare person is interested in stealing funds. Many put in their own money. They understand the urgency. If six dogs need sterilisation before the next heat season, they know the difference between six dogs and 36 new puppies in a few months.”

For Shukla, the stray dog debate is about more than just animals. “Cruelty to animals reflects a society that picks on the weak. Animals cannot retaliate, complain or fight back, so they are the easiest targets. The same society will also mistreat women, children and the elderly. A society where animals are safe is a society where everyone is safe.”

She invokes Mahatma Gandhi’s famous words: “The greatness of a nation can be judged by the way it treats its animals.”

India’s Supreme Court orders stray dogs released to New Delhi streets in modified ruling

How a court’s ruling ripped open India’s decades-old debate over stray dogs

Rabies warning as grandmother dies after being scratched by stray puppy in Morocco

Hero dog saves 67 lives before landslide flattens village

World’s most populated country told to have more children

Canada and India name new ambassadors nearly year after expelling top envoys

Pakistan floods force mass evacuations as Sikh holy shrine inundated