Some of the strangest mammals on the planet just got even stranger. It turns out that echidnas — spine-covered, egg-laying mammals with beaks that shuffle through the undergrowth of Australian forests — probably evolved from a water-dwelling ancestor, a new study finds.

The discovery upends scientists' assumptions about the unusual mammals' origins and is a rare evolutionary event, researchers say.

"A fair few mammals have evolved from living on land to living in the water, but for an animal to go the other way is very rare," Sue Hand, a vertebrate paleontologist at the University of New South Wales in Australia, told Live Science.

There are four living species of echidnas, sometimes known as spiny anteaters, all sitting in the Tachyglossidae family. Three species are found only in New Guinea and the fourth is found there and widely in Australia

Previously, researchers thought echidnas and their semiaquatic relative, platypuses (Ornithorhynchus anatinus), descended from a land-roaming animal, with the ancestors of platypuses then venturing into the water. Both animals are monotremes, the only living mammals that lay eggs rather than giving birth to live young.

To shed more light on echidna evolution, Hand and her colleagues reexamined a humerus (upper forelimb bone) from the extinct monotreme Kryoryctes cadburyi, which lived in what is now southern Victoria, Australia, 108 million years ago, during the Cretaceous period. This species may have been an ancestor or relative of both modern platypuses and echidnas, according to the researchers.

Whether K. cadburyi lived exclusively on land has been debated. Previous analysis of the bone, which was — discovered at a site called Dinosaur Cove, in the early 2000s revealed that it looked similar to bones found in echidnas.

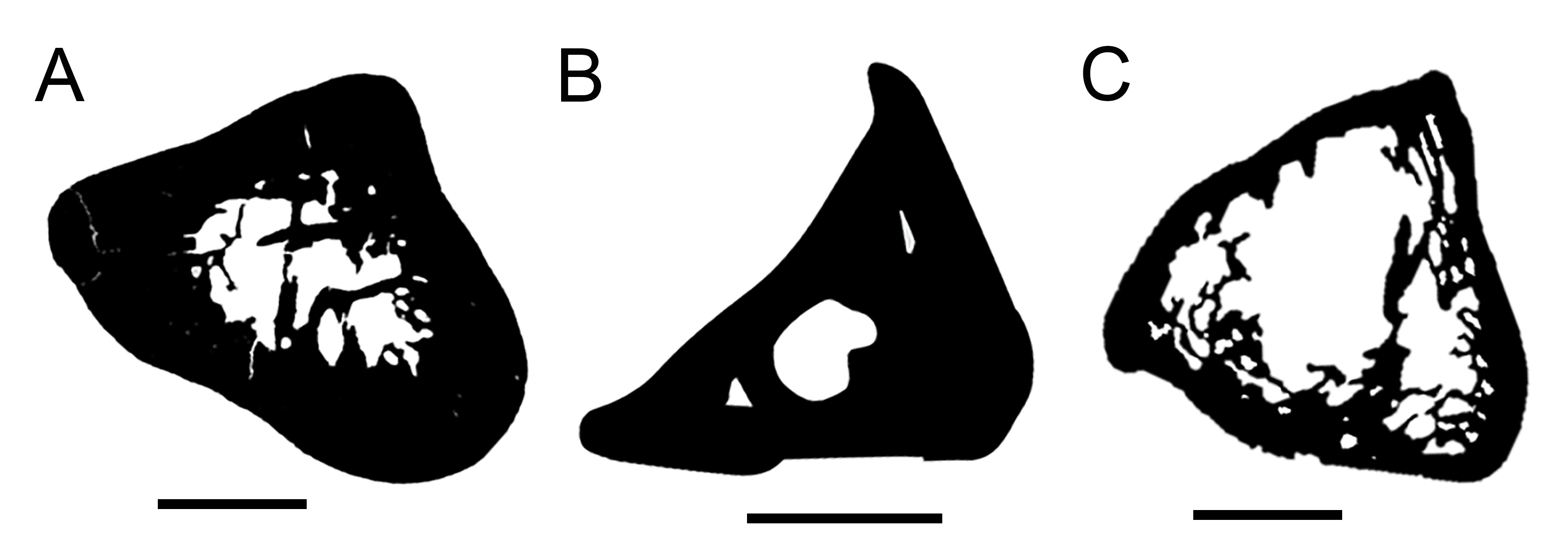

By examining the surfaces of bones, scientists can discern clues about how related animals may be, Hand said, but what's inside the bone can reveal hints about the animals' lifestyles. So the team did micro-CT scans to view the internal microstructure of the bone.

"Modern platypuses today have distinctive bones," Hand said. "They have very thick bone walls, and echidnas are almost the opposite, having quite thin bone walls. So, we were really interested to see what their common ancestor might have looked like."

Despite resembling an echidna bone on the surface, the ancient humerus had thicker walls and a reduced cavity for bone marrow. "We were surprised to find that the internal structure looked more like a platypus than an echidna," Hand said.

Such heavy bones would act like ballast, making it easier for the animal to dive below the water's surface. This means that K. cadburyi was likely a semiaquatic burrower and that the monotreme family used to be semiaquatic, the researchers concluded.

The ancestors of echidnas then moved permanently onto land, and their bones became lighter as they adapted to a new way of life, the researchers said in the study, which was published April 28 in the journal PNAS.

Because of the dearth of fossils from platypus and echidna ancestors, it's not clear when this transition to the land happened. Most of their extinct relatives have been identified solely from their teeth and jaws, and the K. cadburyi humerus is the only monotreme limb bone from that period discovered so far.

Ready to switch

There are many instances in which mammals have evolved from living on land to living wholly or partly in water. These animals include whales, dolphins, seals and beavers, Hand said. But it's virtually unheard of to see mammals evolve in the opposite direction.

"It has happened before in the fossil record, but the more aquatic a mammal becomes, the harder it would be to go back to land," she said.

However, mammals that are semiaquatic burrowers, like modern-day platypuses, would be the ideal group for being able to go either way, she said. This is because they are adapted to both land and water.

This isn't the only clue that echidnas have a watery past. When echidnas are developing, their beaks have receptors for detecting small electrical currents — which in other animals are typically used for finding prey in the water. Platypuses have even more of these receptors.

In addition, echidnas' hind feet, which are used for burrowing, point backward, much like platypuses' hind feet, which the animals use like a rudder when swimming.

"Platypus-like fossils date back 100 million years, but the oldest echidna fossils are less than 2 million years old," said Tim Flannery, a paleontologist at the Australian Museum in Sydney, who wasn’t involved in the research. "The paper adds to the evidence that echidnas had platypus-like ancestors, and is another brick in the wall in what is becoming an irrefutable case," Flannery told Live Science.