Seven-year-old Shahida had no idea her world was about to change that Tuesday in February. One moment she was with her parents in Cherai, a beach town in Kerala’s Ernakulam; the next, she was separated from them and put in a police jeep with her two brothers- all without any explanation.

On February 4, 2025, the children’s parents Dashrath Banerjee and Mari Bibi were arrested by the Ernakulam Rural police under multiple sections of the Foreigners Act, on suspicions of being undocumented Bangladeshi citizens illegally residing in Kerala. While Dashrath was taken to the Mattancherry sub-jail, Mari was sent a hundred kilometres away to the Viyyur Central Jail in Thrissur district.

The couple, who said they are originally from West Bengal, had been living in Cherai, collecting and selling scrap items, for the past 15 years. All three of their children were born in Kerala, and speak fluent Malayalam both at home and outside.

According to Dashrath, the children were home when the police picked up him and his wife. Hours later, all three children were taken to the police station.

While the parents were put in jails, the cops dropped Shahida off at a girls' home. Her brothers 13-year-old Azid and nine-year-old Azim were taken to a boys’ facility. The siblings met only once in the next 10 days, briefly at a children’s cultural event.

For weeks, the children had no clue where their parents were. It was only about 20 days later that they received a phone call from their mother Mari. Now, she is allowed to speak to the children over the phone every Saturday. However, it has been more than two months since Dashrath last spoke to his children.

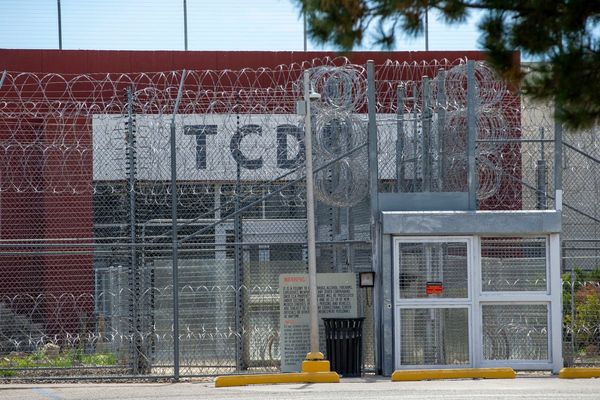

The Ernakulam police's crackdown on undocumented immigrants, under 'Operation Clean', has led to the arrest of around 50 suspected Bangladeshi migrants. It has also had human consequences, including the traumatic separation of families like that of Dashrath.

The operation has sparked criticism over the treatment of children and migrants, drawing uncomfortable parallels with controversial immigration policies abroad, particularly the US' family separations of immigrants. The state’s CPI(M) government has not issued a public statement on its official position on the crackdowns by the police.

While police cite legal mandates, activists argue the enforcement violates children's rights and lacks due consideration for the deep roots many migrants have established in Kerala over decades.

‘Where is home?’

Dashrath and Mari have been charged with violation of visa norms (Sections 14A, 14B, 14C) under the Foreigners’ Act, along with document forgery (Section 336(2)) and fraudulent use of electronic records (Section 340(2)) under the Bharatiya Nyay Sanhita (BNS).

But according to Dashrath, he is Indian, hailing from West Bengal. TNM had earlier spoken to Dashrath and family while reporting for our series on migrant workers in Kerala.

"I came to Kochi when I was 10 years old. Before that, I remember collecting scrap at a railway station in Kolkata.” He said he doesn’t remember where he was before that; his earliest memories are of being in and around Kolkata. "I didn’t have parents, I used to live with a few relatives, but I don’t remember much about them either,” he said.

“One day, [when I was 10] I boarded a train to Kerala. Upon reaching here, I wandered around hungry, picking up scrap items. Then I met a man named Swami, and started working for him," Dashrath recalled. Swami acted as an adoptive guardian to Dashrath, who eventually built his scrap-dealing business.

When Dashrath turned 22, he traveled to Kolkata, married Mari, and returned to Kerala with her. "Our children were born here, and they all attend the government school in Cherai," he told TNM, adding, “My life is here in Cherai, in Kerala. This is home for my children, they speak Malayalam at home and outside.”

When the police turned up at their doorstep in February, the children were abruptly taken from the only home they had known. Within a day, they were moved to a different environment, forced to attend a new school near their care home.

Azid and Azim have some understanding of what happened. "They told me their parents were taken away by the police. But their uncertainty and insecurity are beyond words. They are scared, haunted by fear," said George Mathew, an activist and social worker who works with migrant workers.

Shahida, the youngest of the three, still struggles to comprehend the situation. She remained silent for days after being placed in the care home. "It took 15 days before she started speaking," George said.

It was only after George visited Dashrath in jail and informed him about the children that the father learned they had been placed in care homes. “When I met him in jail, Dashrath had no idea where his family was. He hadn’t spoken to his children in weeks," says George.

After George submitted a request, jail authorities forwarded a letter to the Child Welfare Committee (CWC), stating that Dashrath wished to speak to his children over the phone.

‘I was framed’

The incident in February wasn’t his first run-in with the law. In 2022, during a similar wave of arrests of alleged illegal immigrants by the Kerala police, Dashrath was taken into custody by the Munambam police for allegedly harbouring Bangladeshi immigrants. However, after verifying his documents, the police released him.

According to Dashrath, he possesses original identification documents, including Aadhaar card and ration card, to show that he is Indian. He even purchased five cents of land in Cherai, where he had been living with his family. "I have all my documents, except a passport," he said.

He alleged that he was framed by a local resident against whom Mari had earlier filed a sexual harassment complaint. "Two years ago, when Dashrath was arrested for allegedly providing protection to Bangladeshi immigrants, Mari used to rely on an auto driver for commuting to the police station, jail, and other places. Later, he allegedly attempted to sexually assault her. The family then filed a police complaint," George said.

Dashrath alleged that this person framed him in an act of revenge. “Since several arrests were taking place at the time, [the driver] knew that police would arrest me if such information was given,” he said.

Why separate a family?

Despite several crackdowns on illegal Bangladeshi immigrants in Kerala, children are rarely detained, as it is mostly men who migrate alone, with their families usually remaining in their native villages or towns.

Between January and February this year, around 50 migrant workers were arrested in Ernakulam district under the Foreigners Act, in what the police dubbed ‘Operation Clean’. In almost all cases, only men were arrested; Dashrath’s was an exception, where his family was also involved.

There is no legal protection for minors who get entangled in the messy business of immigration policies; Shahida, Azim, and Azid, who were picked up during the crackdown in Cherai are proof. Jail authorities told TNM that if an inmate submits a petition, all necessary measures will be taken to facilitate communication between the children and their parents.

The police say the separation of families as part of law enforcement is justified. Ernakulam Rural SP Vaibhav Saxena told TNM, “If both husband and wife are undocumented migrants, they are sent to jail. Since the children are minors, they are placed under the care of child protection services. As a law enforcement agency, we are bound to act in accordance with the law.¨

Martin Puthussery, a Jesuit priest and an activist who works among migrants, said that as a signatory to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, India, and by extension the Kerala police, is obligated to ensure that families are not separated.

A 2022 report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights said that annually, more than 3 lakh children are detained across the world for migration-related reasons. The report noted that 77 countries are known to still detain children for the same reasons. “Urgent steps must be taken to amend restrictive national migration laws, policies, and practices that arbitrarily separate children from their families, given that the best interests of the child must be the primary consideration.”

When illegal migrants are arrested in India, adults are held in judicial detention. While children under the age of six are allowed to stay with a parent, those older than six are relocated to shelter homes, by the Child Welfare Committee.

A 2015 study by the Mahanirban Calcutta Research Group highlighted numerous cases of Bangladeshi families being detained, and children separated from their parents in India.

It is no different from the United States' Zero Tolerance policy of 2018, a highly controversial decision made by the first Donald Trump administration. Between April and June 2018, approximately 2,000 children were separated from their families as they attempted to migrate to the US without proper documentation.

On June 26, 2018, a federal judge in California issued a nationwide injunction, temporarily halting the separation of children from their parents at the border and ordering the reunification of all separated families within 30 days.

What the police say

A special branch officer told TNM, "We could not keep the children in jail with their mother as all of them are older than six years. We ensured they are in safe places and that their education and other necessities are not denied.”

The special branch officer added that migrants working in Kerala, who lack proper documents, generally tend to keep a low profile. “They come here to earn a living. People say they don’t commit crimes, and in fact, they are very cautious about that. But when we receive tip-offs, we have to arrest them because that is what the law requires. If we arrest one person, a hundred others start making calls,” he said.

Speaking to TNM, Ernakulam Rural SP Vaibhav Saxena said that the crackdown was carried out under his initiative. “The arrests were made on a large scale after the Ernakulam Rural Police, under my leadership, formulated a strategy. Since Aluva has a significant migrant population, we felt the need to act proactively. We had received multiple reports about Bangladeshi nationals residing here. Based on strategic changes aimed at identifying their hideouts, we also gathered inputs from mobile SIM service providers.”

The SP said that many of the arrested people held Bangladeshi identity cards. “Most of those arrested are from economically weaker sections. A few possessed Bangladeshi passports, while some had Bangladeshi ID cards. However, 90% of them did not have valid Bangladeshi passports,” he said.

Between January and February, around 50 migrant workers were arrested in Ernakulam district, under the Foreigners Act. By mid-April, Vaibhav Saxena was deputed to the National Investigation Agency.

According to data accessed by TNM from various jails in Kerala, around 200 foreign nationals have been incarcerated for various periods in the 15 years between 2010-2025 for violating the Foreigners Act, 1946, the Passport (Entry into India) Act, 1920, or the Immigration (Carriers' Liability) Act, 2000.

Currently, around 80 foreign nationals remain in different jails across Kerala, excluding those held in transit homes. A majority of them are accused of being undocumented Bangladeshis.

‘Wanted’ lives

Several migrant families had taken shelter in Cherai after fleeing from a settlement some 30 kilometres away in Kalamassery in Ernakulam last year. Under pressure from local residents who accused them of being “criminals and sex workers”, municipal officials in Kalamassery had bulldozed their huts. But they were not safe in Cherai either.

In May 2024, a family in Cherai shared a similar experience with TNM. Ali (28) lived near Cherai with his wife, their one-year-old child, his sister, brother-in-law, and their elderly parents. That day, his 75-year-old father, Muhammad had recounted how they had fled to Wayanad from Cherai in 2022 when a major police crackdown took place.

"They arrested some people in Cherai, claiming they were from Bangladesh. Fearing arrest, we fled to north Kerala and only returned after a few months. It was a struggle, especially with children and pregnant women. Finding proper work was difficult," he said.

Ali’s family is now missing again from Cherai. Neighbours told TNM that they may have fled once more following the recent arrests. When TNM attempted to reach Ali, his phone was switched off.

Sahir*, who fled the Perumbavoor region following recent arrests, had earlier told TNM that he has no documents to prove his citizenship. "My great-grandfather migrated from Bangladesh to West Bengal. Back then, it was easy, they just had to cross the Teesta River. I’ve heard my grandfather talk about how they would wait for the water level to drop before crossing. They would camp in villages near the river on the Indian side. I don’t know where I was born as I don’t have a birth certificate, but I do have an original Aadhaar card," Sahir said.

He described how many of his relatives still live in Bangladesh, and they often travel there to attend weddings. "It’s not just Bangladeshi immigrants, even Indians go there and get married sometimes. Parts of West Bengal and Bangladesh share the same culture," he explained. Sahir also claimed that cross-border migration continues even today, often facilitated by bribes to Border Security Force officials.

TNM was unable to locate him when we visited the area in February this year. According to a neighbour, Sahir has left Kerala.

An atmosphere of fear

About 10 km from Cherai, near Munambam, lies Mannam, where a two-storey house once sheltered nearly 54 migrant workers. As soon as TNM entered the building, Rafiqul and Salam, who were preparing their dinner, hurriedly pulled out their passports and other documents from their bags and showed them to me. Despite our assurances that we weren't there to verify their nationality, they continued holding the documents, their hands trembling.

The fear from the midnight crackdown on January 30 still lingers. Around midnight, a large contingent of police officers, including members of the Anti-Terrorism Squad, stormed the house. The building, owned by Harshad Hussain, a local Congress leader and construction contractor who provides manpower for construction projects, became the centre of a sudden raid.

"They came in, took all of us into custody, searched every room, and confiscated our documents. The next day, 27 persons were arrested, and the rest were released,” Rafiqul recounted.

He added, “We all lived together; we had no idea some of them had fake identity cards. They were just like us, migrant workers from West Bengal. We never asked them exactly where they came from. The police said their documents were fake." The police later arrested Harshad, and he remained in Aluva sub-jail for three days on charges of providing protection to undocumented workers.

Following the arrests, the CPI(M)’s youth wing, Democratic Youth Federation of India (DYFI) staged protests against Harshad, accusing him of sheltering ‘illegal migrants’. However, the DYFI leadership said they were not aware of this, dismissing it as a local protest.

While many of the state’s Left politicians refused to react on record against the arrest, they have expressed displeasure at the police action against the labourers.

Notably, the CPI(M) politburo had criticised the way in which the US shackled and deported undocumented Indians, calling it “deplorable and unacceptable”. Kerala Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan had said at the Thrissur district CPI(M) conference on February 11 that US action should be seen as a grave insult to India.

"I am a contractor. I keep copies of the identity cards of all the migrant labourers I employ. I provide them housing and other facilities, apart from their daily wages, which is Rs 1,000 per day for construction work. They have been working with me for four years, and until now, there has never been an issue. They were never involved in any crimes. How was I supposed to know they were illegal migrants? If I had known, why would I have sheltered them?" Harshad asked. He also alleged that the police seized copies of all the Aadhaar cards in his possession.

Harshad said that he realised many of the Aadhaar cards were fake only after the police told him so. "They confiscated two Bangladeshi passports from two of the arrested workers. The others had no proof to establish whether they were Bangladeshis or Indians," he said.

Many migrant families in and around Cherai and Munambam – mostly scrap collectors and dealers – fled to West Bengal or other districts in Kerala, fearing arrest ever since the police crackdown in January.

This report was republished from The News Minute as part of The News Minute-Newslaundry alliance. Read about our partnership here and become a subscriber here.

Newslaundry is a reader-supported, ad-free, independent news outlet based out of New Delhi. Support their journalism, here.