This has been a year of failure in the sharing economy. WeWork’s initial public offering flopped. Uber and Lyft’s stocks have sunk way below their IPO prices. Airbnb faces a safety crisis. Ofo is on the verge of bankruptcy. Didi Chuxing is struggling with resuming its carpooling service after drivers murdered passengers.

The bursting bubble has forced Wall Street and investors to question their judgment, startups to revamp their growth strategies and governments to consider how to regulate the emerging sector.

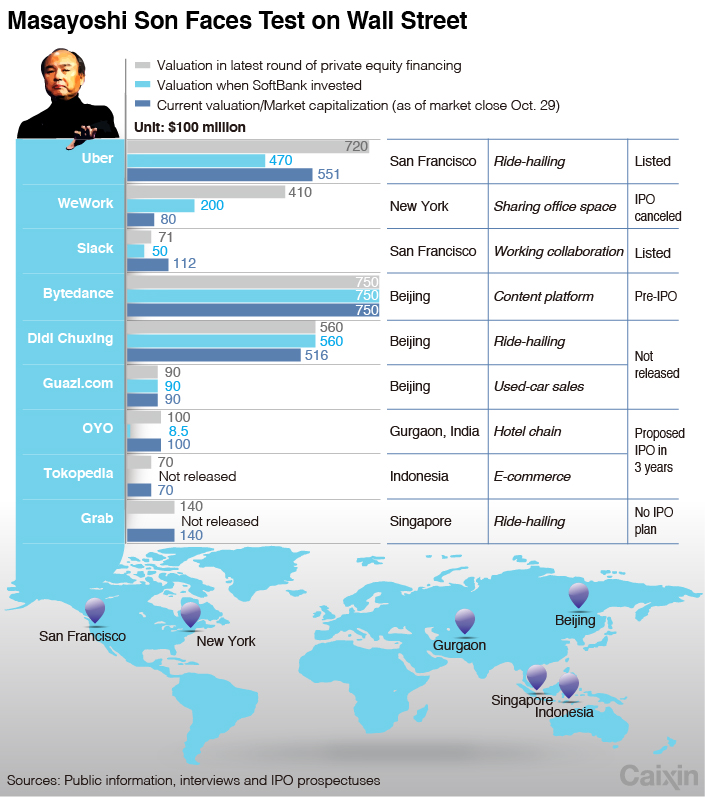

WeWork created the most dramatic scene after the shared-workspace provider canceled its initial public offering (IPO) and stuck private equity investors led by Japan’s SoftBank Group with catastrophic losses. In the July-September quarter, SoftBank’s Vision Fund wrote down investments in more than 20 other companies, including Uber, as the sharing economy startups failed to deliver profits.

While SoftBank is one of the most-exposed tech investors, the sector’s rough 2019 is sending ripple effects broadly through the nascent sharing economy industry. The failure of WeWork’s IPO and the disappointing stock performance of already-listed companies show that investors in public markets have been more realistic than private equity investors like SoftBank. It’s expected that there will be more reverse valuations of tech companies between the private and public markets.

Private market investors value space for imagination, while public market investors look at profit and cash flow to evaluate businesses, said Gui Zhaoyu, founding partner of JG Investment and a former managing director of the leading private equity company Carlyle Group.

Investors are now nervous about the “high-growth, high-cost, difficult-to-turn-profitable” model, and the prospect of a recession makes it even harder to expect public markets to pick up the check, an executive at a Silicon Valley private equity firm told Caixin.

With negative sentiment in the public markets, private equity investors’ enthusiasm for startups has also dimmed.

Global venture capital funding fell 7% in the third quarter to $50 billion, while U.S. venture-backed startups raised $26 billion last quarter, a 15% decline from the second quarter, according to a report from market intelligence platform CBInsights and consultancy firm PwC. The number of deals fell 16% to 1,304. Financing in the San Francisco Bay area, the hub of tech startups, declined 19%, the report showed.

Investment in China is also cooling. Private equity and venture capital investment in the telecommunications, media and technology industries fell 12% in the first half of 2019 from the second half of 2018, PwC said in a separate report. The 878 deals that disclosed financial terms raised a total of $14.9 billion, a record low in for the past three years. The number of large deals decreased significantly in the first half of 2019, with only 29 transactions valued at more than $100 million, down by half from the second half of 2018, the report showed.

In Beijing’s Wangjing district, an area housing many Chinese startups, the vacancy rate of grade A office buildings reached an unprecedented 15%, the most recent data showed.

The number of investor exits via IPOs also slumped. In the third quarter of 2019, 22 U.S. venture capital-backed tech companies exited, down from 33 in the second quarter, PwC’s report showed.

The SoftBank experience may serve as a cautionary tale for private equity investors. On Oct. 22, the Japanese tech investment giant behind WeWork announced a deal to buy out about 80% of the beleaguered company, which is in danger of running out of cash in coming weeks. The deal valued WeWork at about $8 billion, down more than 80% from the $47 billion valuation when SoftBank participated in a previous round of financing in January.

Before the buyout, SoftBank had already poured more than $9 billion into the startup, a bet too big to fail. So SoftBank doubled down, bringing its total equity investment to more than $13 billion, even though other investors were increasingly concerned about WeWork’s chaotic corporate governance and mounting losses and the eccentric behavior of CEO Adam Neumann.

Investor’s Remorse

Two weeks later, SoftBank founder and Chief Executive Officer Masayoshi Son acknowledged the WeWork investment as a mistake after SoftBank reported its first quarterly loss in 14 years.

SoftBank posted an operating loss of 704 billion yen ($6.5 billion) in the July-September quarter, dragged down by a combined loss of $8.2 billion on the WeWork investment by SoftBank and its Vision Fund. During an earnings conference call Nov. 6, Son admitted poor judgment and turning a blind eye to problems at WeWork.

“My investment judgment was poor in many ways, and I am reflecting deeply on that,” Son said. It was a remarkable admission for the 62-year-old veteran investor, who is well known for his bold bets on technology startups.

SoftBank poured $7.6 billion into Uber in early 2018, buying shares from existing investors for $48.77 a share and new shares at $33. As of Nov. 8, shares of the ride-hailing company traded at $27, down about 40% from the $45 IPO price in May.

In addition to Uber, SoftBank invested in almost every major ride-sharing company, including Didi Chuxing in China, Grab in Southeast Asia, Ola in India and 99 in Brazil, with investments totaling more than $20 billion.

None of these sharing economy startups has turned a profit. Uber lost $7.4 billion for the first nine months in 2019. WeWork posted a net loss of $1.6 billion in 2018 and $690 million in the first six months of this year. Didi Chuxing reported a net loss of $1.6 billion in 2018.

IPO or Not

The bleak reality has forced SoftBank to be more cautious about the timing of IPOs. Son said the Vision Fund would now look to list its portfolio companies when they are closer to achieving profitability, which could mean longer waits for investors to exit.

SoftBank-backed ride-hailing startup Grab has been talking about an IPO since 2014. Chief Executive Anthony Tan once said the Singapore-based company might consider an IPO when the number of bookings reached 2 million a day. Now the average number of rides on Grab has reached 46 million a day as of March, but the CEO said the company is in no rush to go public because it has enough money from SoftBank and other investors for its expansion plan.

Another SoftBank portfolio company, Didi Chuxing, is also “not in a rush” for an IPO, according to people close to founder and Chief Executive Cheng Wei.

The WeWork fiasco and the potentially longer exit periods may complicate SoftBank’s fundraising plan for a second mega fund to invest in artificial intelligence. SoftBank announced the launch of its Vision Fund 2 in July and said it expected to raise about $108 billion, based on a series of memorandums of understanding. SoftBank is counting on exiting from its current investments to raise cash for its own $38 billion contribution to the new fund.

Expansion Slowdown

The startups themselves are under pressure to cut costs and slow their global expansions.

After the takeover by SoftBank, WeWork announced a “90-day game plan,” including divesting its noncore businesses and making workforce cuts. In its core business, the company is considering exiting some Hong Kong office buildings, according to a Bloomberg report citing people familiar with the matter. It also has put its expansion plan in mainland China on hold.

As part of efforts to cut costs, Uber in August stopped honoring staff work anniversaries with giant helium balloons, which cost the company more than $200,000 a year. The company has also had three rounds of job cuts this year, including the most recent layoff of 350 employees in October.

Regulatory Challenge

Another challenge facing sharing economy startups is a regulatory push on worker rights and safety issues.

The once-booming bike-sharing industry in China has left millions of abandoned bicycles and dozens of failed startups after local governments banned companies from introducing more bikes to reduce the public litter and congestion caused by illegally parked bikes. Ofo, one of the few remaining bike-sharing companies, is struggling to pay its massive debts to suppliers and users.

Didi Chuxing took its controversial carpooling service offline for more than a year after the killing of two female riders in four months last year led to regulatory scrutiny of the company’s operation.

In the U.S., Uber and Lyft face a regulatory push for better labor protections for drivers. California passed a law in September requiring them to treat drivers as employees rather than independent contractors. This could potentially increase the companies’ costs by 20%-30%, experts estimate.

Airbnb has met setbacks in multiple cities around the world that have passed laws restricting short-term rentals. The home-sharing platform is also in a safety crisis after a fatal shooting Oct. 31 at a California Airbnb rental home that left five people dead.

Backed by venture capitalists, these sharing-economy startups have made their services a part of daily life for millions of global consumers. Now, with rising doubts among investors, pressure to turn profits and increasing regulation, whether they can continue to be economically accessible has become the question.

Contact reporter Denise Jia (huijuanjia@caixin.com)