This article is also available in French. La version française est disponible ici.

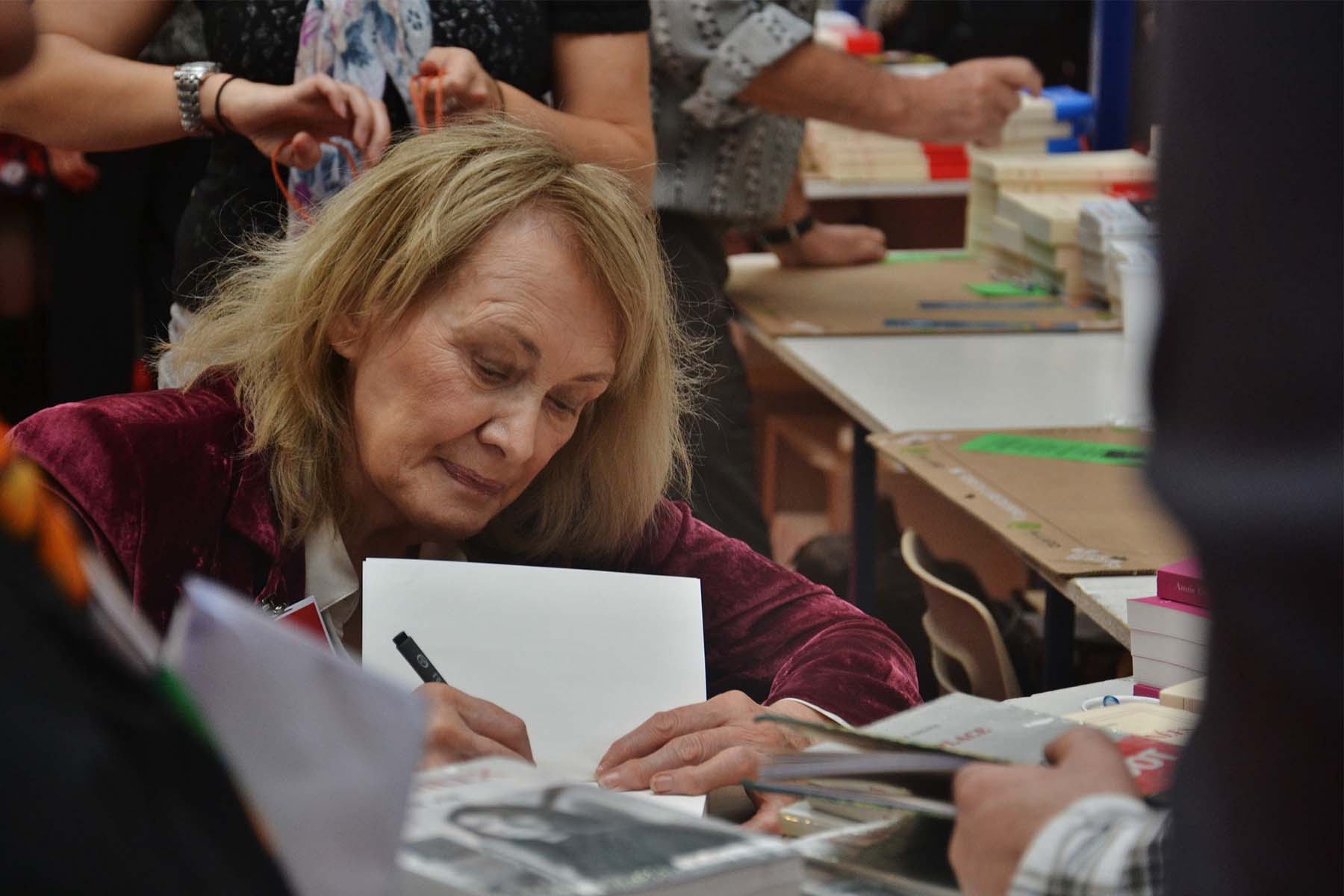

Annie Ernaux welcomed me into her home in Cergy, France, last November, a little over three weeks after she was awarded the 2022 Nobel Prize in Literature, to speak about the letters she exchanges with her readers. What follows is the latest in a series of conversations I have had with the author of, most notably, Passion simple (1991; Simple Passion, 1993), L’événement (2000; Happening, 2001), Les Années (2008; The Years, 2017), and Mémoire de fille (2016; A Girl’s Story, 2020).

Since the 1974 publication of her first book, a largely autobiographical novel titled Les armoires vides (Cleaned Out, 1990), the French writer has explored her own life and the experiences of other women, people of her generation, her parents, and those who are often forgotten by society. As she told me over the following conversation, readers’ letters mean a great deal to her—and some have helped shape her life and work.

This conversation has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

—Karin Schwerdtner

In your article from 1994 in which you consider the reception to Simple Passion, you say that critics and journalists are typically “unable to grasp the true reading experience or perceive how readers inhabit a book and draw from it.” You believe that in order to somewhat assess this true reading or rendering of their work, writers must “converse with their readers and, most particularly, read the letters they send.” For you, these letters are extremely important since they reveal how your books are being received.

If readers take the time to write, I owe them something in return. For me, answering letters is my duty but also a task I truly enjoy. I have such an emotional response to the letters, especially those that are more personal and sensitive. Readers don’t simply recount their own stories but rather react to my work based on their life experiences.

When you say that some letters are personal and sensitive, do you mean that your readers point out what resonates with them in your books?

“Resonate” is an apt term to describe how a book touches something in a reader’s life. The letters that mention this resonance give me an unexpected window into how my work reflects a reader’s own experiences and journey. I might then notice certain things I didn’t originally consider important in a book. I cherish these letters. I store them in cardboard boxes or shoeboxes, and already before the Nobel Prize, I could fill two or three boxes a year.

Do you also keep emails?

Yes, but I don’t print them out. Because I’ve had the same email address for years, I can dig up old messages I exchanged with people who are now gone. I’ll never want to delete these messages.

Whether it’s a letter or an email, correspondence from readers is proof that my books are, that they exist for people other than me. When I finish a book, that is to say, when I emerge from writing, I don’t know what the book is. It’s readers who let me know, in a way. The letters themselves are tangible evidence that my books are reaching an audience. Hanging on to this proof is important to me. If I were to donate these letters, as some writers do, to libraries or universities, they would become something else—something to be studied and analyzed, for example. They would lose their emotional connection to me.

Are readers sometimes willing to confide in you in their letters?

I sometimes feel that readers write to me about things they’re unable to say aloud—in other words, the unspeakable. I’ve confronted the unspeakable myself, as my first book, Cleaned Out, certainly reveals in its look at social stigma and illegal abortions. The same can be said of A Girl’s Story.

We don’t always know how to approach writing about the unspeakable. For me, it becomes a true writing challenge. I’m thinking, for example, of a man who wrote letters to me for over ten years and eventually disclosed a terrible secret in a letter. He revealed everything in this letter. In his case, he had been censoring himself. He then asked me to write his story for him, but I could not, of course, do that.

This isn’t an isolated incident. To paraphrase André Breton, the stories of women and men “have followed me everywhere.” I remember that, back in the summer of 1976, I was writing my second book [Do What They Say or Else] alone in a studio in the mountains. An anaesthesiologist, who’d performed abortions using the Karman method when it was still illegal, came to see me one Sunday with her partner and her daughter. She told me a great deal about her life and asked me to write about her liberation as a feminist. I never did so directly, but I thought of her with sadness and pain when, upon finishing A Frozen Woman, I learned the news that she’d taken her life [in 1980].

In an interview with Pierre-Louis Fort for Ernaux [2022], an issue of Cahiers de L’Herne devoted to your work, you say you were surprised that you were able to see through to the end a long-term book project—The Years—in which you were convinced there would be little interest but that, in the end, has been read by thousands. You say, “I was pleased with this collective living appropriation.” Can you expand on this notion of “living appropriation”?

This expression reflects what I often hear in the letters I receive: “Everything you write, I share and feel.” Similarly, when I offer up material from my archives, I share it. For example, when a publisher decided to reprint Retour à Yvetot [in 2022], I added a foreword and excerpts from my diary and included additional photographs and letters I wrote to Marie-Claude, the childhood friend I speak about in A Girl’s Story. These letters are a glimpse into my life at the time. I reread what I’d written and decided not to change a word since the letters express what I felt then and what I still feel today.

When you entrusted some of your letters to Anne Strasser, a researcher interested in how The Years and A Girl’s Story were each received at the time of their publication, you had said: “Some are from loyal readers, but there are no friends, loved ones, writers, journalists or literary critics among them: I would call them ‘lambda’ readers.” Were you describing readers who have been reading your work for a long time?

My loyal readers are people who have written to me since my first books came out. Some of them are now in retirement homes. Some still write to me. Occasionally, the children of the people who used to write to me will take over, or at least reach out to me, after their parent has died. It’s very touching.

In your latest book, The Young Man [forthcoming in English in September 2023], you write, “Five years ago, I spent an awkward night with a student who had been writing to me for a year.” An earlier book, L’usage de la photo [2005], co-written with the photographer Marc Marie, also refers to a letter that leads to a love affair. What place do you feel readers’ letters have in your work?

My relationship with Marc Marie developed at a time when letters were no longer enough, at which point we met in person. But our relationship did start with letters, and even after it ended, we kept up our correspondence, no doubt because we lived neither together nor in the same city. (Marc Marie has since died; I was notified of his death by a letter sent to me by his cardiologist.)

Around the time when Happening was first published [in 2000], you wrote, “What is remarkable in the letters from women who have had either an illegal or an elective abortion is that, for these women also, this is clearly still a ‘happening’ in their life. But unlike the mail I received when Simple Passion [Passion Simple, 1991] was first published, these letters tend to convey little detail. Readers do not expand much on their experience.” Might things have changed since then? What do letters from women in the past few years say?

I said, then, that letters from women usually didn’t include detailed stories or descriptions of their own experiences. There has been a change in the past twenty years, probably because of #MeToo but also because the film adaptation of Happening [released in 2021] shows the reality [of abortion]. Women who would have felt unable to tell their story are perhaps more willing to do so now.

In an unpublished interview from 1992, you say, “By the time people read my work, I’m no longer the same person who wrote it . . . For me, the past is a dead letter.” What do you mean by “a dead letter” in this case?

My past seems to me like a bygone era captured on film. I feel I’m moving forward and seeing my life experiences as images left behind, becoming like palimpsests.

This same notion also comes up in The Young Man. About your relationship with this young man, you say you aren’t repeating or duplicating your past but rather rewriting it, as though your life were a “strange and never-ending palimpsest.”

Yes, like a rewriting of the past. Even though I’m not sure this is an ideal approach, I do feel that I am living my books and writing my life. I probably also express this same sentiment in my diary, which hasn’t yet been published. I won’t publish it during my lifetime, but I won’t place any restrictions on publishing it—or even on publishing my early drafts, papers, and notes, some of which can now be consulted at the Bibliothèque nationale de France. In my diary, I always try to stay true to my original goal: to write down what I feel with no attempt to create a perfect journal. Unlike some people, I don’t view a diary as a place for moral, philosophical, or intellectual thought. I aim for total spontaneity.

I imagine you can’t allow yourself total spontaneity in your email nowadays, particularly after receiving the Nobel Prize.

I don’t have the same freedom in writing letters or emails [to others, whoever they be] that I have in composing diary entries [for myself]. I follow certain rules, and the Nobel didn’t change that. But now that I receive many more emails, responding to them is much more time consuming, and my responses tend to be brief and delayed. That said, I don’t like leaving emails unanswered. Knowing, today, that a considerable number of emails remain unopened in my inbox leaves me feeling terribly guilty.

The authors thank Jessica Novial for her assistance with audio transcription.