On the transcontinental car journey that he re-imagines in Lolita, Vladimir Nabokov, a serious lepidopterist, records that he 'caught some very good moths at the neon lights of a gas station' in Texas. When he discovered a new species of butterfly in the Grand Canyon, he named it Neonympha dorothea. Photograph: Raul Touzon / Getty Images / National Geographic

Ever since it began to soak our streets in the 1930s, sodium light has been taken as a sign of not always happy urban sophistication. Tom Wolfe, JM Coetzee and Rose Tremain are among those who have exploited it. But John Betjeman was first, ranting against the ‘yellow vomit’ thrown out by the new ‘gallows overhead’.

Photograph: Fox Photos/Getty Images

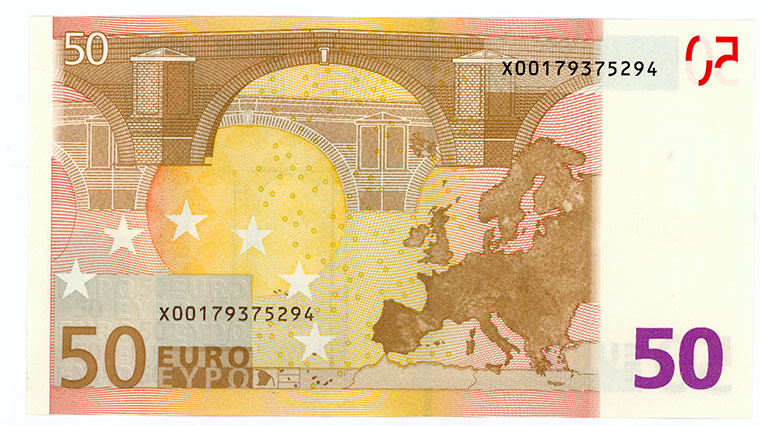

Like most banknotes, the euro incorporates various security features to deter counterfeiters. These include fluorescent dyes. Such dyes can be based on many chemicals, but somebody, somewhere, went to the trouble of choosing europium (Eu), first discovered in 1890 and named after the continent. Thus the currency named for an ideal of European harmony is impregnated with an element named in celebration of the very same idea. Photograph: Guardian

Long before it was known, the element cobalt traced blue trade routes around the globe from its principal source in Persia. It colours the ceramic facade of the grand mosque in Isfahan, Ming porcelain, Venetian glass, Delft tiles, police station lanterns and bottles of Bristol Blue. Photograph: Getty

Calcium is the element we most associate with the absence of colour. Apart from snow, our similes for whiteness are calcareous – white as marble, alabaster, chalk; white as ivory, bone or teeth; white as pearl. Out whitest icons – the White House and the White Cliffs of Dover – are calcium too. Photograph: Holger Scheibe/zefa/Corbis

Various elements are named after the places in Europe where they were found, from copper in Cyprus to strontium in Strontian, Argyllshire. In the US, where places were named after most of the elements discovered, it’s the other way round. Here’s, surprisingly, there’s an Antimony, Utah, Sulphur, Oklahoma, and Boron, California, home to the world’s largest borax mine. Photograph: Harry Taylor / Dorling Kindersley

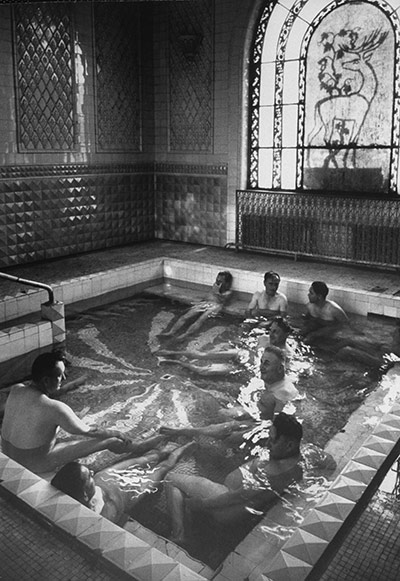

The Radium Palace Hotel in Jachymov, Czech Republic, promises treatments based on ‘the healing effect of radon-rich waters that flow deep below the surface of the Earth’. You can even book into the Madame Curie suite. Not far away, another spa town still rejoices in the name Radiumbad. Photograph: Stan Wayman / Time & Life Pictures / Getty

From Richard Strauss’s opera Der Rosenkavalier to F Scott Fitzgerald’s Great Gatsby, silver indicates virginal purity as it did in classical times. These days, the evangelical movement, The Silver Ring Thing, encourages young Christians to remain chaste, or if it’s too late, to ‘embrace a second virginity’.

Photograph: Siphiwe Sibeko/Reuters

Arsenic-based greens were popular in Victorian wallpaper. William Morris argued strenuously in favour of traditional vegetable dyes. Odd, then, that X-ray analysis of Morris’s own designs shows his green came from copper arsenite, while a red rose pattern was the vermilion of mercuric sulphide – ‘a very dangerous piece of art!’ as the investigator put it. Photograph: Stapleton Collection/CORBIS

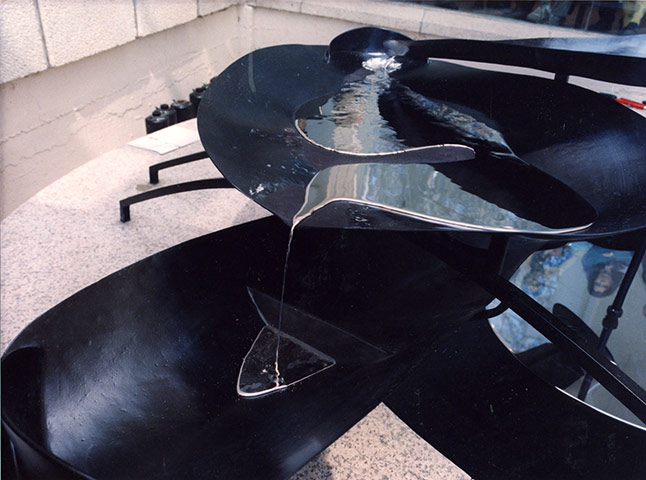

Alexander Calder’s Mercury Fountain was displayed in the Spanish Pavilion at the 1937 Paris Exposition alongside Picasso’s Guernica. One of the most imaginative war memorials ever devised, it commemorates the mercury miners of Almaden as drops of mercury aggregate, separate and shape events before their ultimate absorption into stillness. The Mercury Fountain is on show now at the Joan Miró Foundation in Barcelona Photograph: Marti Catala Pedersen