With the NFL concussion lawsuit on track to its first legal victory since the cases were first brought forward in 2011, former players and their families are condemning the deal for providing insufficient compensation for their injuries – especially those who have suffered from the degenerative brain disease chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE).

Of the 20,000 people estimated to qualify for the suit, at least eight have opted-out of the settlement, which could cruise through a fairness hearing in November because of the low rate of objections. Those who did opt-out can now pursue individual lawsuits against the league, which has the highest revenue of any US sports league at about $10bn annually.

One of the people who opted out is Joe DeLamielleure, who was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 2003 after playing as an offensive lineman for the Buffalo Bills and Cleveland Browns from 1973 to 1992.

In September 2013, a team at UCLA diagnosed him with CTE as part of a pilot study. He says that he was never diagnosed with a concussion in his football career, despite estimates that he took more than 225,000 hits to the head. “I walked around for 13 years with a headache, I thought it was normal,” DeLamielleure told The Guardian. “From July until December – whenever the season ended – so it was just part of the game.”

He loved being a part of the NFL and said he was addicted to playing. His son played for Duke, and both have talked about how the issues of head injuries are quiet while things like back and shoulder injuries were openly discussed.

In the past few years, however, head trauma has become a hot topic for football fans and players as research on the effects of the game come to light. Researchers at the Boston University CTE Center said in September that of the 128 brains from football players they had examined, just under 80 percent had tested positive for CTE.

“I’ve got five grandsons, it’s up to their mom and dad if they want to play, but their grandma won’t let them,” said DeLamielleure.

He said his wife, a pediatric nurse, is currently providing for the couple’s healthcare. He is rejecting the settlement because he believes he will not receive any money from the settlement since the suit does not recognize CTE diagnosis in living players.

“We were injured playing an American game on American soil and they won’t take care of you,” DeLamielleure said. “It’s a work-related injury – why are they changing all the rules if it wasn’t?”

He realized that he could have suffered serious injuries from head trauma that he suffered while playing after the death of his friend, Mike Webster, who played in the NFL from 1974 to 1990.

At the time of his death in 2002, Webster was reportedly homeless and displaying signs of serious mental illness: memory loss, dementia and depression. Webster was the first American football player to be diagnosed with CTE. Bennet Omalu, the forensic pathologist who performed the autopsy on Webster, came up with the diagnosis and has since said dozens of other deceased players had the disease.

At least 75 other former football players have been diagnosed with CTE since that first diagnosis. Families of some of those players, like Junior Seau, who killed himself in 2012, opted out of the deal.

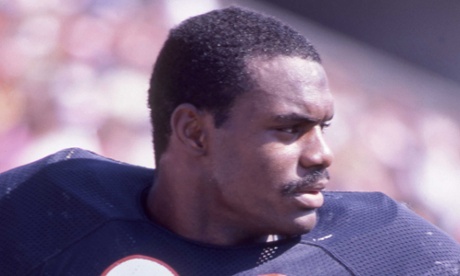

The family of former Chicago Bears defensive back Dave Duerson filed an objection, which allows them to still qualify for compensation from the suit. Duerson killed himself by shooting himself in the chest in February 2011 and sent a text message just before he died to his ex-wife, Alicia, that said: “Please, see that my brain is given to the NFL’s brain bank.”

Attorneys for Duerson and nine other former players said in an objection that the settlement “disenfranchises the families who will inevitably suffer the horrific ramifications of CTE,” because players diagnosed with CTE after 7 July 2014 are not covered by the suit.

At least 10 other objections were filed on behalf of dozens of players ahead of Tuesday’s deadline.