Sister, released in 1987, is widely acclaimed as Sonic Youth’s best album. At the time of its release, it was acknowledged as a step up for the New York City alt-rockers in terms of writing and sonic quality.

Evol, released the previous year, had already served notice that the band was moving toward a more mainstream sound. Sister was the record that made good on that promise, delivering commerciality without compromise.

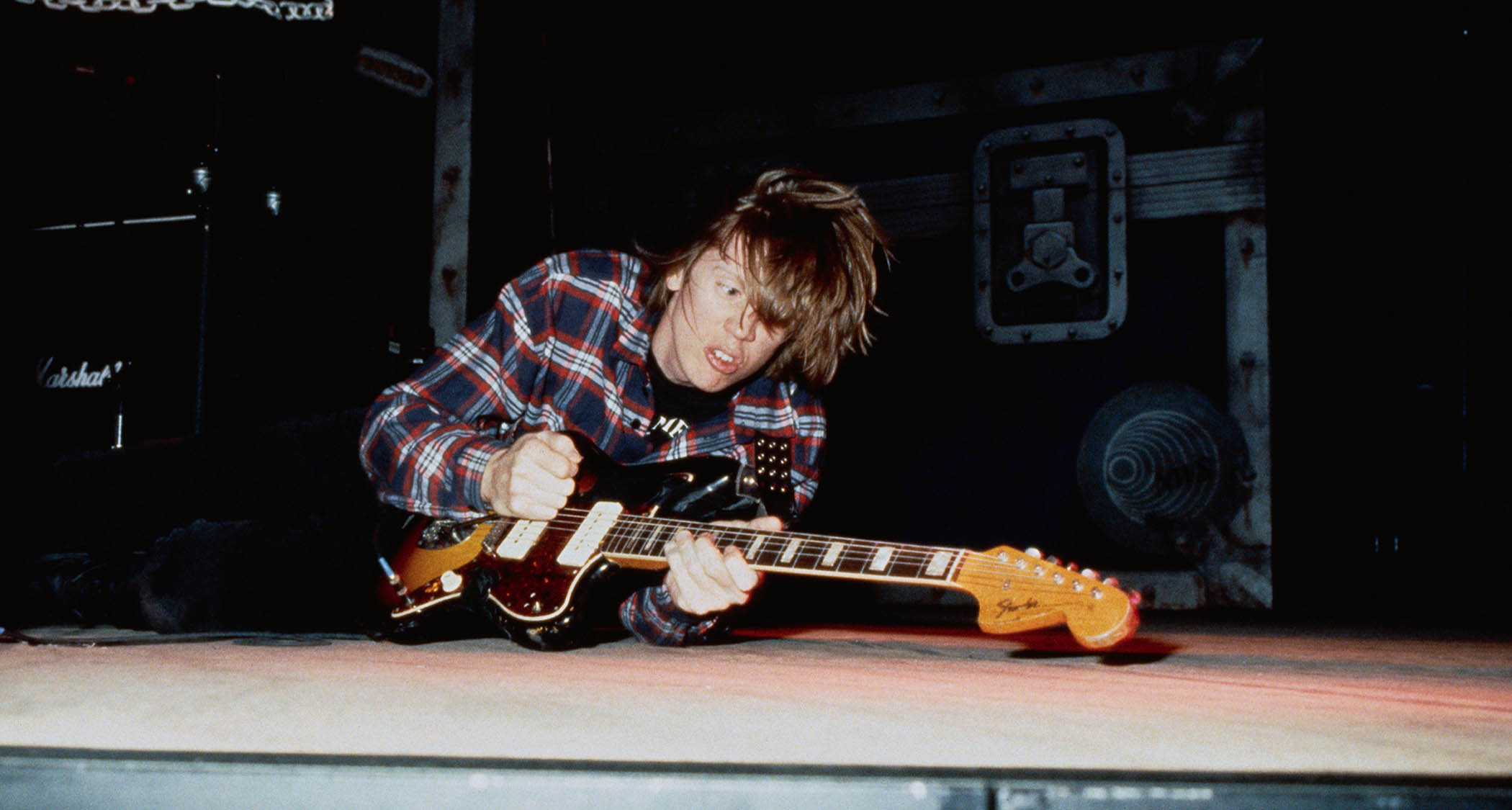

Guitarists Thurston Moore and Lee Ranaldo had already adopted a wildly experimental approach to their playing, inventing unique alternate tunings, using prepared guitars – with drumsticks wedged under the strings (among a number of radical approaches) – and playing behind the bridge.

The fact that they could weld such radical unconventionality to songs that delivered memorable melodies and solid hooks was a testament to their creative prowess.

Sister is often cited as one of the key albums of the Eighties. How do you feel about it these days?

“I knew we were moving into a territory that was possibly less reckless than the previous albums we’d recorded. We were more focused on concision as far as songwriting was concerned. At that point, when I was in my late twenties, I remember thinking we were becoming more refined and sophisticated as a band, in the context of what kind of band we had been.

“By that, I mean one that isn’t defined in the traditional high technique bands dealt in. I think Sister was when we were able to combine what we were doing with alternate-tuned guitars and alternate song structure into more accessibility for a broader listenership. I think it marked us entering a new era of sophisticated sonic songwriting. I think we were allowing ourselves to grow up in public.”

In terms of the writing, would all the songs have been fully formed before going into the studio, or did things change a lot once it came to putting the songs down?

“I think everything was definitely fully formed. We had it together. We knew we had to be as ready as possible because we were recording at Sear Sound [in New York City], which was something of a bespoke studio. It cost a bit of coin, so we had to make sure we were acting responsibly toward our budget. [Laughs] We went in there knowing there was no time to fool around – and we were ready.

“We had rehearsed that material quite a bit in a very tiny room on the Lower East Side. The room was so small that we couldn’t turn the amps up loud. It meant we had to play fairly quietly, and in a way, I think that defined how that record sounded. There were no blasters on there except maybe White Cross and Hot Wire My Heart. The songs had a contained, linear quality, which continued as an aspect of the band for our subsequent albums.”

What was the process in terms of you and Lee dividing the guitar parts?

“It was totally organic. A lot of songs were predicated on me bringing up riff ideas that I would have come up with in my apartment with Kim [Gordon, bass]. Once I brought them into the rehearsal room, Lee, Kim, and Steve [Shelley, drums] were free to create their own ideas around the structure.

“Lee brought in Pipeline/Kill Time, which was fully composed by him, but again, we were all free to play what we wanted. Nobody ever brought in a song and said, ‘Look, this is how you have to play that part’ or whatever. You could never be precious with a song you brought to the band. You’d show it to your wolf brothers, and they’d tear into it. [Laughs]

“That was why none of our records had ‘lyrics by’ or ‘music by’ or whatever. They were all credited to Sonic Youth. Everything that everybody contributed was of equal value.”

Did you make the album quickly? Were you a first-take kind of band?

“We did work very quickly on that record because, as I mentioned, the studio time was expensive at Sear Sound. I think, in general, we’d usually go for about six takes of a song before it started to become stiff.

“I was very into expediency, but very rarely do I recall us getting a song that was perfect on the first take. I was always keen on getting in and out of the studio; I always felt it was a bit like being in a boat on a lake where you can never escape. [Laughs]”

What were the main guitars you and Lee were using at the time?

“I was still playing a Fender Duo-Sonic that I’d got for a couple of hundred dollars. I always thought it looked a little dinky though on my six-foot-six-inch body. [Laughs] But around the time we started the album, we had gotten into Jazzmasters and Jaguars. We were moving away from the junk-store guitars we’d been using, like old Hagstroms and Harmonies.

“They were falling apart on us. We stuck with Fender. Lee was also using a Telecaster on the album. I felt very in tune with the Jazzmaster. I think the longer neck it has – compared to the Duo-Sonic – was the key. We’d been looking at new guitars as we’d made some money from touring.

“I remember Lee pointing at a Jazzmaster on the wall in a store and saying that that’s the guitar Tom Verlaine uses, and I thought that was good enough for me. I still play a Jazzmaster all the time – even now.”

You and Lee were renowned for using alternate tunings that you had created. How did that come about?

“The first album [1983’s Confusion Is Sex] was in traditional standard tuning, funnily enough. We were aware of musicians using different tunings in downtown New York in the scene we were in – the art-rock composers like Glenn Branca. I was amazed by that, but I didn’t think it could be employed in a traditional rock band lineup.

“I remember saying to Glenn that [our] guitars were so bad that we couldn’t really make them work for us. He came over to my apartment with six guitars, three under each arm – no cases or anything – and threw them onto the futon. [Laughs] It was amazing. He had one that had six .10-gauge strings all tuned to E, for example. We started to really delve into alternatives to standard tuning.

“I’d just strum the open strings and adjust them until I liked what it sounded like, and then I’d make a note of what the strings were tuned to in that tuning. This was before you could buy tuners very easily – I think all you could get were those big [Conn] Strobotuners. I used to tune Kim’s bass to a Black Uhuru record, then tune our guitars based on that.”

Given how many unconventional tunings you were using, did you ever find yourself getting lost, trying to remember where you were on the neck?

“I never saw myself as much of a guitarist in standard tuning anyway; I never really engaged with traditional tuning. I didn’t feel like I needed to express myself in that tuning and never felt comfortable in standard. In fact, in some ways I felt more under pressure because the world was so full of great players who were in standard, and I had no interest in trying to compete with them.

“I never really thought of myself as a guitar player until well into the game. My brother, who is five years older than me, is a great guitar player. He’d be shredding in his bedroom, and I’d sneak in sometimes to steal a guitar. I wanted to be a drummer, but I didn’t have the coordination.”

When you listen to Sister now, do you hear anything you wished you’d done differently?

“It has a really nice resonant quality. Sear Sound was a wonderful studio, and I think that had a lot to do with the sound of the record. I wouldn’t change a thing. When I hear about bands remastering a record, it makes my eyes go funny. [Laughs] Even when the Sonic Youth records were remastered, all I thought it did was make them louder, which I don’t think is necessarily a good thing. It’s kinda like the record is waving its arms in the air or something.

“Even worse is if a band tries to re-record an album years later because they think they can play it better. Big mistake. The clumsiness of youth is what makes a record what it is. There are parts on Sister that are sore-thumb moments, but that’s the beauty – the bruises of your youth.”

You’ve just released Flow Critical Lucidity, your first solo album in three years. I appreciate the way it combines peaceful, mellow ambience with a vaguely unsettling undercurrent.

I’m interested in investigating a more meditational aspect of rock music, and this record enabled me to do that

“Yeah, I guess that’s right. I had recorded quite a lot of material for it. The sequence of the album is pretty much the songs that worked together with this gentle quality. I left a couple of wilder songs off the record as they were a little too jarring.

“I’m interested in investigating a more meditational aspect of rock music, and this record enabled me to do that. It allowed me to examine the meditational exchange between the creative impulse and the natural world – the woke world and the world of dreams.

“It was written during a residency I was doing in Switzerland. I knew I was going to be doing the album, so I wrote the songs over two weeks. I brought the rest of the musicians over from London; we set up in a small rehearsal unit and I’d show them my ideas.

“I recorded the songs on a Zoom recorder and was initially tempted to put them out [in that format], but I thought better of it. They were almost good enough, but once we got in the studio they became far more majestic.”

- This article first appeared in Guitar World. Subscribe and save.