We don’t hate you,” Zoe Alexander told the men on trial for the 2015 Paris terror attacks. Her brother Nick, 35, was the only British national killed when gunmen stormed the Bataclan Theatre in Paris during a rock concert, as part of a series of coordinated attacks in the capital . He was the merchandise manager for the California-formed band Eagles of Death Metal, who were playing to a sold-out crowd when the ambush took place.

Zoe’s words made headlines at the time, a remarkable display of grace and forgiveness amid the horror of such an atrocity. Marking the 10-year anniversary of the attacks, she tells The Independent why letting hate win would have felt like a “disservice” to her brother, whom she remembers as being in “a great place in his life, doing what he loved”.

“When something like that happens, you can’t ever envisage what it’s going to be like in 10 years,” she says. “But we’ll be [in Paris] again this year, with the community of survivors and victim’s families. We’ve all stood together and been on this journey side-by-side.”

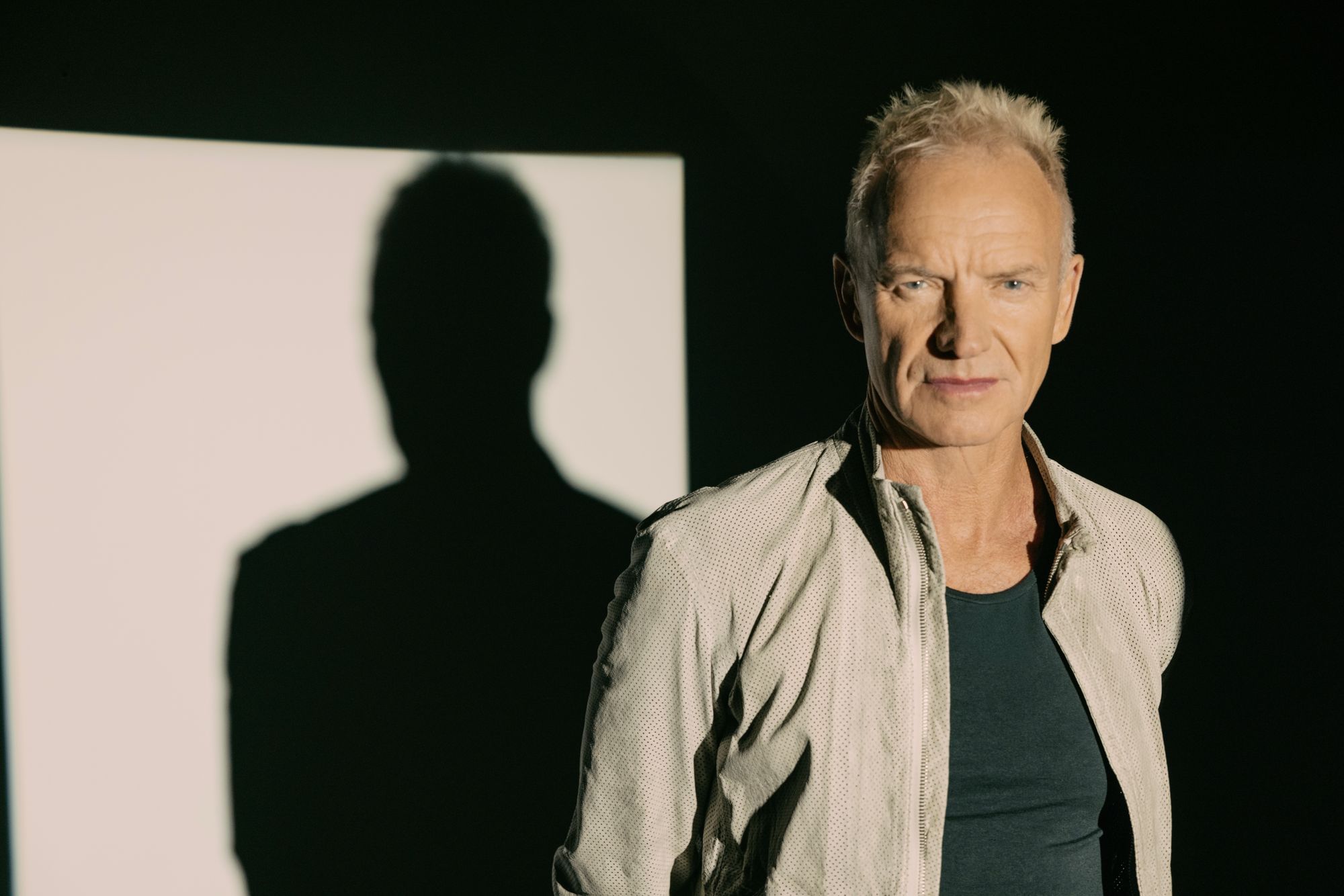

The Bataclan reopened exactly a year after the attacks, in which 90 people died, with an emotional gig by former Police frontman and solo artist Sting. He performed in front of hundreds of concert-goers, including survivors and family members of the victims, a moment he calls a “great honour”.

“I had played there in the Seventies,” Sting tells The Independent. “Nonetheless it was a difficult balance to get right, celebrating the reopening of an historic venue and at the same time honouring the victims and their relatives, as well as some of the surviving staff who were still working there.”

Zoe was one of the family members in attendance. “I wanted to go in and be there,” she says. “I didn’t want to be afraid.” She recalls the tension in the air – roads were closed around the venue and armed police stood guard as guests filed through the doors – “We were all wondering, ‘Is this going to be OK?’”

“There was a palpable tension in the club,” Sting recalls, too. “So I spoke calmly to the crowd in French, explaining the dilemma here and asked if they would join me in a minute of silence. I then performed my song ‘Fragile’, which seemed respectful and appropriate, and after this everything became a little more relaxed, the set curated specially for the occasion.”

During the show, he brought out guests including French-Lebanese trumpeter Ibrahim Maalouf – known for fusing Arabic-influenced sounds with jazz, funk and rock – who joined him for several solos. “At one point I brought some Arab musicians to play with me – I know there was some controversy about this later, but the attack had been an assault on the whole of the city. Parisiennes, Arab and French had all suffered,” Sting says.

Five days after Sting’s performance, I was among the audience for Peter Doherty’s Bataclan concert where the crowd were still, understandably, jittery. One couple murmured to one another about whether they should stay. Another group jumped as a crew member did soundcheck on the drums. Making his debut as Doherty’s guitarist was Jack Jones, poet and frontman for the Swansea-formed rock band Trampolene. He read a set of poetry first – Nick Alexander’s name written on his chest – with one line, “silence is the darkest sound”, ringing loud around the venue.

“That will remain forever one of the most impactful, meaningful moments of my life,” Jones says. It was Doherty who gave a short speech to his band before the show and then wrote Nick’s name across Jones’s chest: “I was so nervous, I was shaking sideways,” Jones says. “It was completely silent when I came out – the whole thing was just super emotional.”

He feels that the whole music community – not just those who played at the Bataclan, but the wider response at the time of the attacks and ever since – felt a responsibility to “carry on, to carry that flame”. Doherty clearly shared this sentiment, as the ensuing gig was a raucous affair at which the frontman stumbled around the stage, knocking into his bandmates and egging the crowd on into some good-natured moshing.

Zoe wasn’t there for Doherty’s gig at the Bataclan, but she spoke to the band beforehand and was touched by their decision not to have a merch stand that night, in honour of Nick. “The Libertines were such a part of his and my musical journey – growing up in London we had brilliant times running around to see them play, and the last gig we saw together was actually The Libertines at Alexandra Palace.” She returns to Paris every year, as do many, to remember their loved ones or to face down the memories of what they experienced that night. “The fact that survivors are still going to gigs, I think that’s incredible testament to [their courage],” she says.

A few years ago, she and her co-organisers changed the name of the trust founded in Nick’s name, from the Nick Alexander Memorial Trust to the Nick Alexander Music Trust. “That was quite an important thing for us, because it shifted it to having more of a focus on the future, and on his legacy. It awards grants for musical equipment to small charities and community groups across the UK, with the first ever grant going towards a ukulele orchestra. “Having all of that music created in his memory, it keeps him alive, in a way,” she says. “He’s still making music to this day.”

Blonde ambition: How Dolly Parton became the Star of the Show

Faith No More’s Roddy Bottum: ‘Today, Kurt Cobain would be on meds a lot sooner’

Jon Bon Jovi: ‘There have been days where I thought I was done’

After his Grammys triumph, a look at Bad Bunny’s unstoppable rise

The Smiths’ Mike Joyce: ‘I’m not on Morrissey’s Christmas card list’