An expert panel of the world's climate scientists finds climate change impacts are being felt earlier than previously expected

ANALYSIS: The world still has a chance to limit global warming at relatively safe levels of 1.5 or 2 degrees above preindustrial levels but other impacts of climate change, like sea level rise, can no longer be reversed in less than a matter of centuries, if not millennia.

The latest report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reviewed 14,000 scientific papers, handled more than 80,000 comments and questions from other experts around the world and had to be approved during a lengthy summit involving representatives of 195 national governments.

While it didn't produce new research, the study assessed the existing scientific consensus. Its conclusions are therefore by necessity conservative - but they still paint a dire picture of the threat the world faces from fossil fuel-caused climate change.

The report found human influence has been responsible for warming of about 1.07 degrees above the 1850-1900 average and that there's still a chance warming can be limited to 1.5 or 2 degrees. However, this will require "deep reductions in CO2 and other greenhouse gas emissions ... in the coming decades". The 2 degree target was enshrined in the 2015 Paris Agreement, alongside a pledge to "to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5C".

In addition, the IPCC said it was "unequivocal" that human actions are the main driver of climate change. "Each of the last four decades has been successively warmer than any decade that preceded it since 1850," the IPCC concluded.

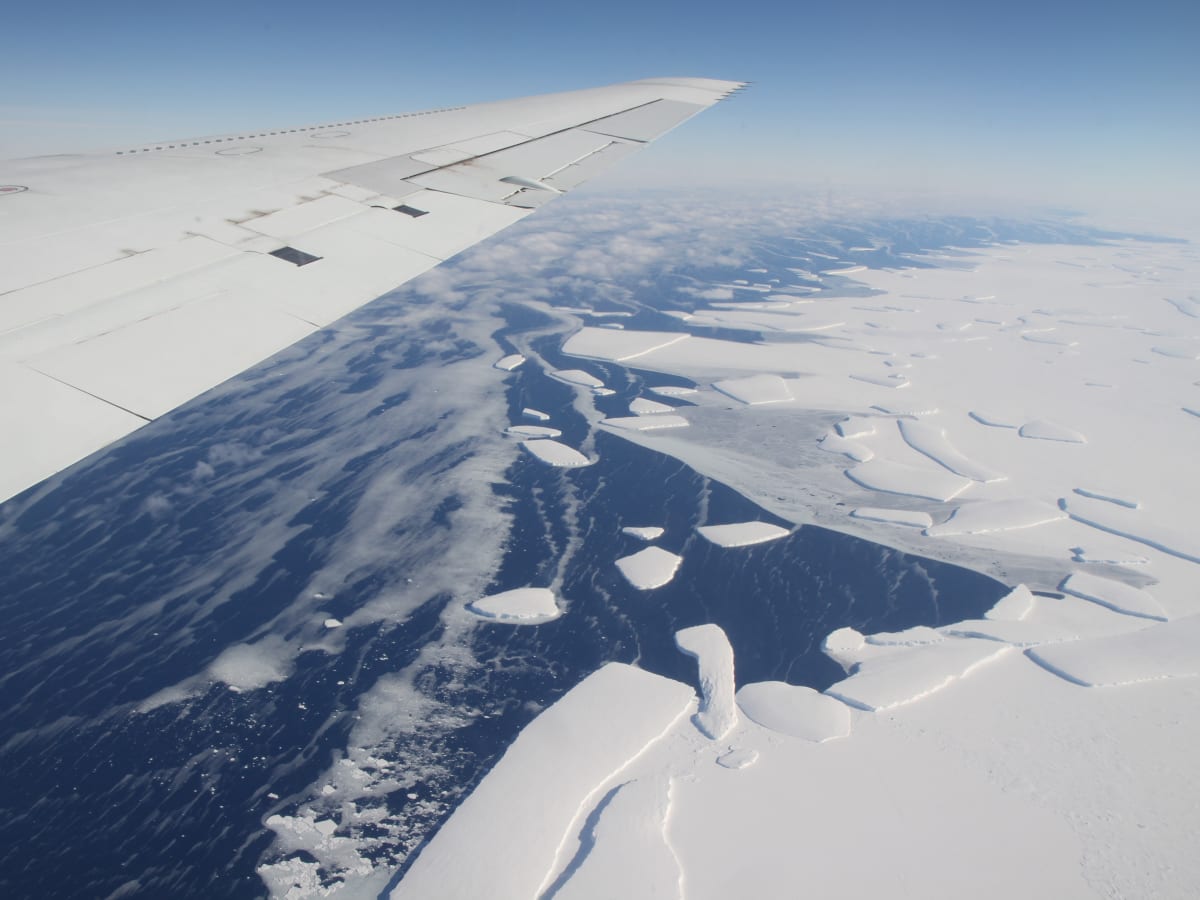

Other impacts of climate change include a likely increase of rainfall, increases in ocean acidification and ocean salinity, global retreat of glaciers and ice sheets, reduced snow cover in the Northern Hemisphere, more frequent extreme heat events, higher sea levels and a likely increase of major tropical cyclones.

Some of these impacts will continue to intensify even if warming is halted. Sea levels, for example, will rise by two to three metres even if warming is limited to 1.5 degrees. If warming is stopped at 2 degrees, sea levels could rise as high as six metres, while 19 to 22 metres of sea level rise would be locked in at 5 degrees of warming.

Glaciers and ice sheets - including those in New Zealand - are "committed to continue melting for decades or centuries".

Climate Change Minister James Shaw told Newsroom the grim predictions from the report "really should give us a kick in the pants to ensure that we have the strongest possible emissions reduction plan by the end of this year".

Methane a focus

One of the key findings of the report for New Zealand was that "strong, rapid and sustained reductions in [methane] emissions" could be crucial to meeting a 1.5 or 2 degree target. That's because methane has strong warming effect on the climate in a relatively short amount of time. Cutting methane could slow warming while emissions of all-important carbon dioxide (which are still rising) are turned around.

Slashing methane could also offset one of the side effects of reducing carbon pollution. The burning of fossil fuels can also produce a range of chemicals called aerosols, which have a net cooling effect on the climate because they reflect sunlight back into space. If we're reducing fossil fuel use, that might initially have no impact or a slight warming impact because aerosols have operate similarly to methane in strongly affecting the climate for a short period of time.

New Zealand's large agricultural sector means methane plays a significant role in our emissions profile. A greater focus on tackling methane emissions could mean greater requirements on farmers to reduce their farm emissions.

Shaw said the report showed that responding to climate change would require a whole-of-economy approach.

"[Reducing methane] only works if you're also reducing your carbon dioxide. It doesn't work if you're not," he said.

"You need to do everything. You can't just pull one lever and go, 'Oh well, we can go easy on one side because we're handling it over on the other side'."

Any effect that the report's conclusions might have on New Zealand's methane reduction targets - to cut emissions of the gas by 10 percent from 2017 levels by 2030 and by 24 to 47 percent by 2050 - wouldn't be something for Shaw to decide, he said.

"What I'm trying to do is to build up the habit of acting on the advice of the [Climate Change] Commission."

He was hopeful that the commission would take the new IPCC report - and two more documents forthcoming in 2022 - into its future advice on New Zealand's emissions budgets. Ahead of the commission's first batch of advice, Shaw had asked it to determine whether the existing methane targets were consistent with 1.5 degrees. In its final advice, it declined to comment on the existing targets and gave only an indicative range for what might be required in 2100.

"That advice that we got around methane was less specific than it could have been," Shaw said.

"But given that the reference case that they were using for pretty much everything [in their final advice] was the previous 2018 [IPCC] report on 1.5 degrees, it makes absolute sense for them to use this report as the reference point for their next round of advice. In that sense, I think it's really helpful that this report has got much stronger information about the role that methane can play in holding the temperature increase to 1.5C."

Risks greater than ever

Shaw said he was optimistic that this report would have a similar impact as the landmark 2018 report on what would be required to limit warming to 1.5 degrees, in terms of spurring on action.

"If you think about the 2018 report on 1.5, that was critically important. We probably wouldn't have that temperature threshold written into our legislation if that report hadn't come out at exactly the time that we were writing that legislation."

Another key section of the new report deals with the risk assessment that each country and region will have to carry out. This includes extreme weather events becoming much more common. An extreme heat event that might have occurred once every 50 years prior to 1850 would occur once every six years if warming was limited to 1.5 degrees or twice every seven years at 2 degrees. At 4 degrees over warming, it would be an almost yearly occurrence.

The continuing sea level rise will also make extreme flooding and associated events more frequent. "Due to relative sea level rise, extreme sea level events that occurred once per century in the recent past are projected to occur at least annually at more than half of all tide gauge locations by 2100," the report found.

Even more drastic events, like the collapse of Antarctic ice sheets contributing up to 2 metres to sea levels by 2100, or the abrupt collapse of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation which redistributes heat around the world, or the self-reinforcing dieback of the Amazon rainforest which stores 76 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide, "cannot be ruled out". While they are not likely to occur under current projections, if the climate turns out to be more sensitive than anticipated and global warming exceeds the anticipated range for a given emissions scenario, these low-likelihood but high-risk events become more likely.

This host of risks reinforces the importance of preparing to adapt to the impacts of climate change, Shaw said. He said the Government's climate change adaptation plan was expected next year, informed by a National Climate Change Risk Assessment released last year. There is also work ongoing around a Climate Change Adaptation Act which seeks to deal with the complex issue of who pays when climate change-fuelled extreme events damage coastal or other properties.

"I think it just shows how important it is that we do that work. Because our communities are exposed to floods, fires, droughts, storms at an increasing rate, and we will leave them exposed if we don't take those actions," Shaw said.

'Time is running out'

Despite the grim news in the report, Shaw said he was still optimistic that the world would rise to the challenge and avert the most catastrophic impacts of climate change.

Covid-19 showed how rapidly we could respond to a clear and present danger. Combined with extreme weather across Europe, Asia and North America, this report will help climate change transition from a far off threat to something that endangers us right now, Shaw hoped.

"I think, actually, our natural ability to respond is now starting to be triggered. The big question is, has it been triggered too late? It is one of those things with climate change: By the time you feel the water boiling, it's too late."

New Zealand-based climate experts greeted the report with a range of reactions, spanning from optimistic to pessimistic. All were clear that the report reiterated that climate change is cause for immense concern.

"While human influence on climate had been assessed as 'clear' in the previous report in this series, released in 2013, this new assessment in unprecedented detail describes the pervasive reach of human influence into many aspects of climate," NIWA principal scientist Olaf Morgenstern said. Morgenstern is also the lead author of the chapter in this report on human influence on the climate.

"Many of these changes are unprecedented in thousands of years; human civilisation has never existed in a climate this hot."

Bronwyn Hayward, a member of the IPCC's core writing team who is working on a report due next year, was hopeful that the new findings would spur greater action.

"In 2018, I hoped that the Special Report would be the end of magical thinking, that we’d stop thinking somehow climate change wasn’t happening. Opinion polling now shows that New Zealanders do accept climate change is real and all ages are increasingly anxious about its impacts," she said.

"We must now avoid a new kind of magical thinking that relying on technology will save us. Instead, we must take real actions to reduce emissions and protect people, biodiversity and businesses."

Nathanael Melia, a senior research fellow at Victoria University of Wellington's Climate Change Institute, said the report fascinated him as a climate scientist and terrified him as a father.

"As a climate scientist, the updated knowledge presented here is as fascinating as it is impressive, and has enabled a doubling down on the IPCC’s confidence in our now 'unequivocal' influence on the climate," he said.

"However, as a human, with a young family, combined with this understanding, the contents of this report are nothing short of terrifying. In the space of eight years since the last report, the language seems to have changed from a position of a 'warning, this could happen', to a position of 'brace for impact'."

And University of Canterbury senior lecturer in environmental physics Laura Revell said "the science will not get much clearer than this".

"The key outcomes of this report are clear: sea levels are rising and extreme weather events are occurring more frequently. The scale of recent changes are unprecedented over many centuries to millennia."

NIWA principal scientist Sam Dean said the report made clear that "time is running out. The IPCC has confirmed that to have a 67 percent chance of staying below 1.5 degrees of warming, the world can only emit another 400 Giga tonnes of CO2 into the atmosphere. At current global emission rates, that’s about 11 years".

"It is understandable that we may be numbed by such a difficult task. However, the IPCC offer hope with their observation that emissions scenarios with low greenhouse gas emissions can achieve rapid and sustained effects in limiting human-caused climate change. We must keep this urgent message from some of the world’s top scientists at the forefront of our minds as we take our all-important first steps towards a net-zero future."