Whatever else it is, Twitter is a place where the average person can subject others to their displeasure. They have been mistreated by Southwest Airlines. They have been angered by the comments of a man who sells beans. They have learned, to their horror, that the father of their favorite indie-pop star previously worked for the U.S. State Department. In posting about these things in a venue where the target of scorn might actually see the complaint—along with perhaps millions of other people—the aggrieved may experience some instant relief. If you want accountability on social media, you tweet.

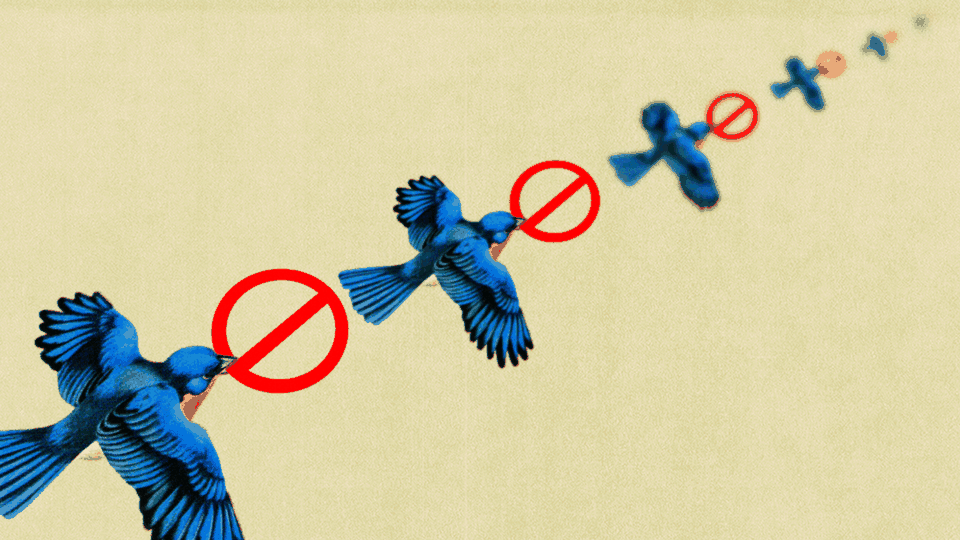

Which raises a weird question: If Twitter withers under Elon Musk, where will we go with our beefs? Even before Musk’s takeover, the platform was supposedly shedding its most valuable users; now many others are expected to leave as the platform becomes glitchier and more toxic.

Twitter has never been perfect, but it has been functional. The options for those seeking justice there exist on a spectrum from the silly to the profound; most are somewhere in the middle. A hideous crime has been committed against Taylor Swift fans by Ticketmaster, and they would like the Federal Trade Commision chair, the Millennial icon Lina Khan, to see their righteous anger and intervene. That’s mostly ridiculous, with a dollop of substance behind it; Ticketmaster isn’t undeserving of scorn. But the balance tips when ostensible do-gooder brands are called out for their antithetical labor practices, or when celebrities and politicians abuse their power to harm the people below them: The dynamic is sort of goofy, given that it still involves an avalanche of tweets supplemented with memes and in-jokes, but the impact is undeniable. The most famous example of this is #MeToo, which has been criticized for its perceived excesses and misfires but which was also awe-inducing in its weight and consequence.

We call most of these events, sometimes in jest, “cancellations”: They appeal to a crowd to second their outrage, and the crowd responds with condemnation of one sort or another. It’s a broad concept, which is one reason cancellation has become a source of anxiety for many people with little else in common, including the centrist establishment of The New York Times’ Opinion section, right-wing beauty influencers, and the writer and legendary Twitter personality Joyce Carol Oates. And Twitter is cancellation’s natural home because of its structure and design. “These are what we call ‘platform affordances’—the characteristics of the platform that make particular kinds of practices easier or harder,” Eve Ng, an associate professor at Ohio University and the author of Cancel Culture: A Critical Analysis, told me.

Nowhere else is such a range of personalities encouraged to interact with strangers via posts that take a second to consume and less than that to share. Hashtags are common on Twitter, allowing users to easily quantify and follow along with a cancellation in progress. Twitter also amplifies attention-grabbing conversations through its algorithmic recommendations and in its controversial trending-topics sidebar. Virality on Twitter is a matter of a large account retweeting something for a new audience, which can then spread to other clusters of accounts, dragging one conversation across many different audiences. “There’s no offline equivalent to the speed with which that happens,” Ng said.

Becca Lewis, a Ph.D. candidate at Stanford who has written about cancellation, told me that Twitter is a place where all users appear to be part of a big, ongoing conversation—not divided up into forums, as on Reddit, or into specific creative niches, as on Instagram or YouTube. There’s a feeling that anyone can talk to anyone, about anything, at any time. “It was a new and revelatory thing when people realized, ‘If there’s a celebrity on Twitter, and I’m also on Twitter, I can tweet directly at them, and there’s actually a nonzero chance that they will see what I have to say,’” she said. “And that became a really deeply ingrained part of Twitter culture.”

Twitter—it’s where you cancel. In a 2020 history, The New York Times referred to the site as “cancel culture’s main arena,” citing early incidents including the 2014 “#CancelColbert” campaign, which sprung up after the official account for The Colbert Report tweeted an offensive joke about Asians, and Gamergate, a prolonged harassment campaign directed first at a few prominent women in the gaming world. The latter is a somewhat unexpected example, but it demonstrates how the mechanisms of cancellation are versatile, and not the sole invention of any one group.

There’s no real parallel elsewhere on the internet. Things like cancellations happen on other platforms: On TikTok, vicious dogpiling campaigns—deployed against non-famous people such as “Couch Guy” and “West Elm Caleb”—are sometimes referred to as cancellations but don’t actually qualify, because they don’t involve a known entity accused of abusing some kind of power, privilege, or platform. On Tumblr, celebrities and pieces of media have long been criticized for being “problematic”—sometimes in the midst of earnest conversations, other times in disputes between warring fandoms. But these conflicts have generally been localized, with complex affiliated lore, limiting their reach. The same could be said for cancellation as practiced on YouTube, where influencers with huge followings are often scrutinized by the proprietors of “drama channels.” There, cancellation means something specific, Lewis told me: losing subscribers and, therefore, revenue.

Cancellation also emerged from a distinct culture on Twitter. The practice evolved from “callout” practices that were common on Black Twitter in the early 2010s, Meredith D. Clark, an associate professor at Northeastern University, wrote in a 2020 paper. She describes it as a “last-ditch appeal for justice” with origins in “queer communities of color”—and Twitter’s unique ability to network different communities turned “the language of being ‘canceled’ into an internet meme.”

The idea of cancellation spread from Black Twitter to Twitter more broadly (maybe first during the era of #IsOverParty hashtags), partly through the fluid state of memes, partly through a tendency in various fandoms to appropriate habits from Black Twitter, and then most obviously through the cultural earthquake of #MeToo. By 2020, cancellation had been co-opted by right-wing politicians and pundits who said that the left was trying to “cancel” history—as embodied by monuments to the Confederacy—along with its political opponents. During the Black Lives Matter protests that summer, then–White House Press Secretary Kayleigh McEnany voiced her fear of the cancellation of the children’s cartoon PAW Patrol (because one of the main characters is a German Shepherd puppy who is a cop). Later, Ohio Representative Jim Jordan called for a congressional hearing on cancel culture, which he described as “a serious threat to fundamental free speech rights” in America. By the end of that year, “cancellation” had become a concept that could apply to anything—including displeasure about Baby Yoda eating amphibian eggs.

When Twitter is gone—or when too many people stop using it, and then the other people stop using it too—“cancel culture” could persist as a silly talking point and bloated meme, but not as the practice we’ve come to know. And this will probably feel bad. For anyone who has sought to correct some kind of perceived wrongdoing on the platform, it will be the end of an era. “Cancellations don’t always—in fact, they very frequently don’t—lead to any real changes or impact on the person who’s being, supposedly, canceled,” Lewis told me. “What they often function more as are community-catharsis events.”

We’ve grown accustomed to having some place to put our stray thoughts about things we’ve seen—big and small—that feel wrong and deserving of attention. In her 2020 paper, Clark described how the platform “allows hundreds of thousands—if not millions—of everyday people to leverage networked collectivity and a sense of immediacy to demand accountability from a range of powerful figures.” She gave examples of celebrities and universities; the list could also include brands, bosses, politicians, awards shows, schools of thought, public-transit systems. (New Yorkers used to love to tweet, “@andrewcuomo fix the subway.”)

Without this ability, we will walk around for a while in a daze, as if with a phantom limb. Something will really be missing.