There is an injury that impacts every football season. This injury has been mislabeled since the day it was named. It remains mischaracterized, too, despite the bevy of stories assigned to explain it every time it afflicts a star player. Because of the mislabeling and the mischaracterization, this injury, despite no shortage of scientific studies attempting to explain it, remains one of the most misunderstood in sports, especially when a superstar such as Joe Burrow or Brock Purdy is felled by this specific malady, to this particular body part, the one upon which seasons and legacies can hinge.

Yes, the humble toe.

To gain a better, more accurate understanding, start with an issue of one specific medical journal from 1976: Medicine and Science in Sports, Vol. 8, No. 2, pp. 81–83. The two authors of this study worked for the medical center at West Virginia University and for the school’s athletic department. They examined the Mountaineers’ football seasons from 1970 to ’74, the first five years the team played its home games on AstroTurf.

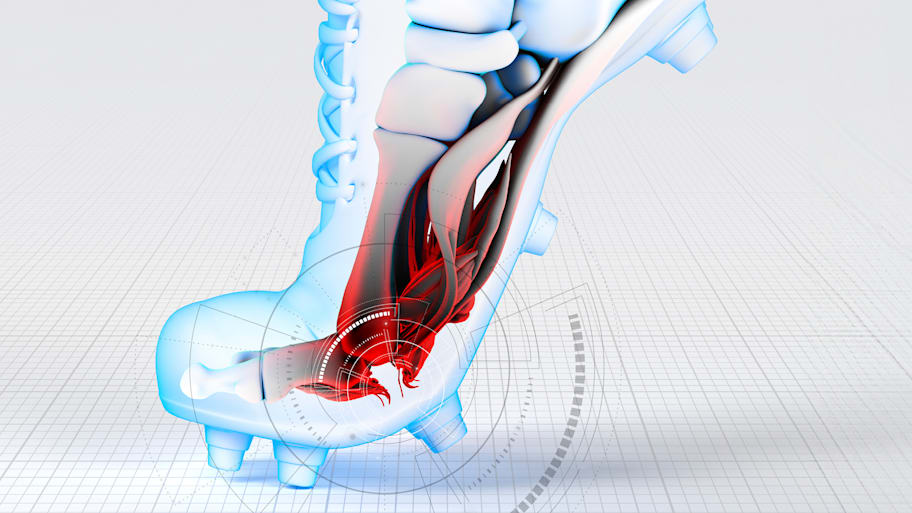

The authors noticed an uptick in one specific injury during those seasons: an increase in sprains of “the plantar capsule-ligament complex of the great toe metatarsophalangeal joint.” They meant the ligaments in and around the big toe. They found 27 such injuries in those five seasons. They also gave the injury a name, one that endures, even now, alongside debates over the primary factors the authors identified nearly 50 years ago: surface hardness and shoe stiffness.

“We have referred to this condition as ‘turf toe,’” they wrote back then.

When Burrow’s turf toe injury upended a promising Bengals season in Week 2, or when Purdy suffered the same injury in San Francisco’s opener, missed two games and then reaggravated his toe in Week 4, the misguided chorus began anew. A toe injury? Really?

Well, yes. That’s the story of all turf toe diagnoses, from that initial paper to now. Sports Illustrated spent several weeks trying to separate fact from fiction and to define an injury that is 1) severe; and 2) painful as hell, regardless of its name.

Just ask Jordan Palmer, former NFL backup quarterback and current private quarterback coach. He was on the phone the week after the Bengals announced that Burrow was likely to miss at least three months of this season. Palmer was explaining why turf toe shouldn’t indicate any lack of toughness. Rather, he was arguing that this injury should be assessed, examined and treated through a far more serious—and far more realistic—lens.

Palmer starts with an analogy. Remember how the mafia was said to handle many of its problems? They broke thumbs, not pinkies. Broken pinkies could be endured. Broken thumbs made every minute of every day more difficult. The same concept applies to toes.

“You use your big toe in terms of creating movement more than any other part of your foot,” Palmer says, while speaking about the injury in general and not Burrow’s specific medical condition. “[Everything] connects to that big toe. You use it to decelerate. You use it to change direction. You use it in creating a movement, applying force to the ground to create leverage, to push your hips in the direction you want to go.”

“In all of the things I teach,” Palmer continues, “that big toe is kind of everything.”

The authors who coined “turf toe” broke this down in that long-ago research paper. They described the medial-lateral motion—movements associated with the ligaments and bones in the foot—as being naturally limited. Those players who suffered sprains of the “plantar capsule-ligament complex”—meaning the big toe and all the ligaments around it—were forced beyond that limited available motion. And that overexertion meant further injuries.

This original study concluded that the best course for avoiding turf toe was a “relatively flexible” shoe and a “relatively hard” surface. The authors wrote that “turf toe results in significant functional disability.” Alas.

Many studies followed the original. Some drew vague conclusions. None have yet proved definitive in terms of how turf toe injuries occur or the best ways to avoid them. SI found and digested a dozen of these studies, then spoke to NFL players, their trainers and medical experts.

What emerged was the story of an injury that should be taken seriously, one that already is by teams and players and their confidants. It’s also a story where the central elements of an article published in a scientific journal 49 years ago are still being debated: shoes and surfaces and turf toe injuries. Even with advancements in science, equipment and recovery techniques, those are still the baseline factors.

Only now, there are more surfaces to play football on, more shoes for athletes to choose from, and, still, more superstars coming down with football’s most mischaracterized injury.

Period.

Over a span of four weeks this fall, SI reached out to 20 players who had been diagnosed with turf toe injuries. Only two, both retired, responded. This subject remains too painful. At least for most. Not Bart Scott, though. He played 11 NFL seasons for the Ravens and Jets as a linebacker and special teams ace, making one Pro Bowl and filling pivotal roles on playoff teams. Nobody ever questioned his toughness.

Scott embodies much of the turf toe misunderstanding. His final diagnosis was labeled that, but also more extreme—proof of the degrees of such injuries, which range in severity but start with the same baseline. There are no “good” iterations, just versions where a bad injury is worse. Scott’s happened in 2012, in the same Week 3 game that Jets cornerback Darrelle Revis tore his right ACL against the Dolphins. Scott’s injury that day ate up far fewer column inches in the New York papers. But it was actually worse than what happened to Revis—Scott tore one ligament off the big toe on his right foot, damaging a nearby bone as well.

When asked how it felt for one toe to completely deconstruct on one play, Scott says he cannot recall exactly. “I’m a dummy,” he says. “I played 13 weeks with it.”

He missed only one game that season, in Week 8, ending a streak of 119 consecutive games played. Otherwise, he says, “My toe was literally in the air the entire season.” He wore shoes that were one and a half sizes larger than usual, so that he could tape that big toe and cut off the front of those oversized cleats. This left that toe—and his injury—exposed, so Scott jerry-rigged foam to cover it, spray-painted the foam black, making his cleats look closer to normal. Sort of. This approach kept his big toe off the ground, making it impossible for Scott to push off with his right foot. He started adding padding underneath those toes, enlarging his Frankenstein creation. Which only further damaged the ligaments he hadn’t torn. He had to turn as if skiing on a football field. He couldn’t stop his momentum, either.

In a December game against the Cardinals, wideout Larry Fitzgerald noticed Scott’s MacGyver-cleats-toe approach. “What the f--- is wrong with that toe?” Fitzgerald asked Scott, whom Fitzgerald then referred to as Ronald McDonald for the rest of that afternoon.

In the offseason Scott underwent total foot reconstruction surgery. That toe, he says, still doesn’t touch the ground. There aren’t enough ligaments remaining. He can no longer curl it.

Scott never played in the NFL again. Most said he had “lost a step” at the end of a long and decorated career. He had actually lost an appendage. “People didn’t realize I was playing with nine toes,” he says.

Turf toe ended his career, as it did for two of his former teammates—Jonathan Ogden, who has said chronic turf toe took the joy out of football for him, and Ray Lewis, who played part of one season after his diagnosis but not at the same level. “I can’t f---ing move,” Scott says Ogden once told him. Steelers linebacker Jack Lambert, as “tough” an NFL player as ever lived, retired due to turf toe and later said that if he had understood the pain this injury would cause him, he might not have played football, period. Same for Deion Sanders. His turf toe led to an amputation.

“I tell everybody,” Scott says. “I want you to wake up tomorrow and go through your day without a thumb. Tape it onto the rest of your hand. Try to do everything without [it]. Write. Drive. Hold onto something. That’s what it’s like not to have [a healthy] big toe.”

The original turf toe researchers were onto something with their examination of AstroTurf. Invented in 1965 by the company Monsanto and known initially as “Chem-grass” when first installed at the Astrodome in Houston a year later, AstroTurf had a significant impact on the condition of big toes. Warren Moon played 17 NFL seasons in his Hall of Fame career, including 10 with the Oilers. In 1996, he was with the Vikings—another team that played indoors—when he injured the big toe on his right foot during a home game.

After the injury, Moon recalls pain shooting through his nerve endings, which led to a recovery Catch-22. The agony abated whenever he was stationary but returned every time he went to stand up, increasing with each step taken. Shoes also exacerbated the torture. When he played, Moon wore cleats with a metal plate inserted into the bottom; it, when combined with reams of athletic tape, ensured the injured toe wouldn’t bend. Which led to another Catch-22: Moon’s toe was protected that way, but it robbed him of necessary flexibility and mobility, adding a psychological imprint. He worried about pushing off too hard with that foot, which impacted his ability to move freely.

“It’s just a very uncomfortable injury,” he says. “And I’m not just talking about playing [with it]. It’s one of the more painful and more difficult soft-tissue injuries you can have.”

Moon is not exactly anti-AstroTurf. He experienced positives and negatives playing on that surface. It was level, which meant no divots or sprained ankles from poor upkeep. Any weather elements—rain, snow, cold that frosted fields—mattered far less than with grass. That combination allowed athletes like Moon to “play faster” and boosted the pace of games. But AstroTurf was also gross, soaking up blood and sweat and leading to turf burns and infections. “It was definitely a dangerous surface when you fell on it,” Moon says. “AstroTurf was deadly. It was hard. And that’s why, for so many years, the Players Association wanted to do away with it.

“Which is when we [got] to FieldTurf, the next best thing compared to grass.”

In the late 1980s, AstroTurf got an upgrade. Shock-absorbing pads were added, along with fibers filled with sand. Football teams, wary of installing a (slightly) better version of the same surface, did not widely embrace the second generation of nongrass football fields.

They would widely adopt the third, the change Moon referenced. FieldTurf was introduced as a better, safer, less injury-dispensing surface in the late ’90s. This surface utilized longer fibers than AstroTurf, each fashioned from combinations of mostly sand and rubber. Those fibers enhanced shock absorption, making it feel more natural to run, cut and plant on. This meant the surfaces played more like grass, requiring far less maintenance and related costs. In 2002, the Seahawks installed FieldTurf at their new home, what’s now known as Lumen Field.

By 2025, there were dozens of versions of this surface—so many with funky names: Revolution 360, Vertex Prime, Prestige XM, Genius, EasyField, PureField Ultra—made by several companies and used all over the world. Some feature three layers of “infill,” meaning the combination of pads and fibers layered underneath. Others have two. Others have what’s known as “low infill,” or less than two full layers. Some use monofilament (individual, straight fibers); others use slit-film fibers (which create nets or honeycomb structures to hold infill); and some use a hybrid of the two. More recently, a new entrant, “sod on plastic,” emerged. That’s the process of layering grass atop plastic, which pushes the roots up so they intertwine, forming a mat of grass similar to synthetic turf. Those mats are at once pliable and unbendable.

As turf surfaces evolved over three decades, introducing fiber and installation options, many in the pro football world hoped or even expected that more data would yield a better understanding of turf toe injuries. There were more of those than ever before.

Thirty years later, the medical professionals agree, primarily, on one thing. It has not.

In the dozen studies SI reviewed and cross-checked with experts, researchers and doctors, they agreed, primarily, on one conclusive element: There remains little in the way of any definitive turf toe conclusions. There is, however, a large, inconclusive body of work to consider.

The American Journal of Sports Medicine (2016) found 963 ACL injuries in pro football from 2012 to ’16 that met the criteria for one study. In those five seasons, researchers uncovered 4,801 lower-body injuries that impacted 2,032 professional players. Those were relatively evenly distributed (2,533 on natural turf compared to 2,268 on artificial) but taking into account the number of games played on each, synthetic turf led to 16% more lower-extremity injuries.

Most importantly, these researchers examined the biomechanics of those artificial surfaces. They confirmed that synthetic surfaces did not release cleats as easily as natural grass did. The increased load of forces on the feet was found to contribute to higher rates of lower-body injuries, including turf toe.

An NFLPA study unearthed higher injury rates on artificial turf compared to grass each year from 2015 to ’22. It also found that 92% of nearly 1,800 players who responded to the organization’s annual team report survey preferred grass fields to any turf versions.

The Operative Techniques in Sports Medicine journal published a paper in 2017 titled “Turf Toe: 40 Years Later and Still a Problem.” It found that up to 45% of NFL players would be diagnosed with this injury in their careers.

In 2023, NBC Sports revealed that, from 2017 to ’22, seven of the 10 NFL stadiums with the highest injury rates played games on some version of synthetic turf. In contrast, seven of the 10 stadiums with the lowest such rates had installed grass fields.

In public comments in recent years, the NFL has debated these and similar findings. Regardless, its players consistently echo the same theme: They fear more injuries, more risk and shorter, less impactful careers simply by playing more often on artificial surfaces, of which there are more all the time—and for the usual reason, money. Artificial surfaces make stadiums more versatile for other events.

Retired college football coach Chris Petersen can add a pinch of anecdotal evidence culled over decades spent on the sidelines. “What I know for sure is that grass is better than turf to play on for all body parts,” he says. “As a coach, standing on the turf, I know how it [made] my back feel compared to grass.” Asked to elaborate, Petersen—who spent 13 seasons at Boise State coaching on the school’s famed blue field—says he regularly needed to stretch while coaching or hang from a pull-up bar afterward to alleviate the pounding his spine took just from standing on synthetic turf.

So, grass fields will fix turf toe injuries, then? Or cut down on the number and severity? No again. Studies, like those above and many others, tend to examine injury rates and surfaces in the most basic sense. That’s how they get larger sample sizes. That data strongly and consistently points to the same conclusion. But it doesn’t account for injury histories, doesn’t delineate between types of artificial turf, and doesn’t include the impact of shoes and their respective flexibility or how both interact with any surface. These conclusions are, in other words and at best, incomplete. And that notion extends to the informed opinions of football’s participants. Even Petersen admits, coaching backaches notwithstanding, “There’s no real, hard conclusive evidence that turf is worse than grass.”

Seven weeks into the 2025 NFL season, Tom Gormely calls from Florida. He is a biomechanics expert with a doctorate in physical therapy. He works with baseball and football players, including many NFL quarterbacks such as Purdy. Like Palmer, Gormely could not discuss his client’s private medical information. But he did add some nuance to how one subset views the broad injury labeled 49 years ago has been changing.

Gormely gives a quick, related physics lesson. Baseball pitchers plant more often than football quarterbacks. Yet he cannot recall an ace rendered out with turf toe. That injury all but requires force to overextend any big toe in any foot. For 99.99% of cases, he says, football turf toe injuries resulted from another player landing on that part of any foot and forcing the hyperextension or planting said foot into turf without give.

He has heard the usual chorus, stuff like, Oh, it’s a toe, who cares?

“What’s injured in a turf toe injury?” he asks. Then he answers his own question, tossing out terms like “flexor hallucis” and “sesamoid” and other ligaments, muscles and tiny bones. “There are a lot of ligamentous, capsular, tendinous pieces of anatomy directly tied to that great toe. Those are directly affected when your toe [extends]. And [that] makes it virtually impossible to sprint, run, plant, cut or do anything—even walk—without significant pain. You can’t just push through!”

Turf toe injuries are confusing, then, because there’s not one injury. There are several lumped under the same misleading umbrella.

The range increases the complexity of treatment and timetables, none of which yet present a definitive, best practice. Asked for the ideal and most feared versions of a turf toe, Gormely launches into an explanation of pluses and minuses but arrives at a broader conclusion: “They all suck.”

The best approach, from the OG paper to now, remains the same: Rest. Allow the injury to heal. Avoid chronic issues. This tracks with the most definitive conclusion in all of the scientific studies.

The Orthopedic Journal at Harvard Medical School published a research paper in 2021 that examined the effect of turf toe injuries on player performance in returns to play. It found that, from 2010 to ’15, only 80% of Grade 3 turf toe sufferers who required surgery returned at all—and none did so in the same season. The Iowa Orthopedic Journal (2019) found that turf toe injuries resulted in “significant” losses of playing time, but players who ultimately returned performed at similar levels compared to before their injuries and compared to a control group. In 2023, The Journal of Foot and Ankle Surgery published its findings, confirming that NFL players who sustained turf toe injuries between 2011 and 2014 did not decline in performance upon returning compared to a non-turf toe control group.

Biomechanical debates continue here, Gormely says, citing studies on cleats and their firmness commissioned by players’ agents and team general managers. SI could not find one publicly available. “It’s still not definitive,” he says.

Changes in understanding, approaching and minimizing the impact of turf toe injuries now occur behind the scenes. They involve physical therapists and orthopedists. Asked if an ideal combination of surface and shoe type will ever be identified to cut down on lower-extremity injuries, including turf toe, Gormely says he’s always optimistic. More tech. More artificial intelligence. More science.

And, ideally, more understanding of big toes and bigger pain. Just don’t bet on that last part. Almost 50 years of history suggest the opposite.

More NFL From Sports Illustrated

This article was originally published on www.si.com as How Turf Toe Became the Most Misunderstood Injury in Sports.