At the beginning of every British autumn we mark the turning season with three immutable certainties: bright chilly mornings, the start of a new academic year and the launch of Strictly Come Dancing. This year sees the 20th series, with a line-up that has sparked nationwide conversations about gender, sexuality and disability.

Last year’s ground-breaking final was praised for its inclusive representation with deaf actress Rose Ayling-Ellis and John Whaite, the first male contestant to dance in a same-sex pairing.

This year’s series demonstrates the BBC’s commitment to continuing its work in challenging norms about who can or should dance – and who they should dance with. As a researcher in the field, my work looks at inclusive dance practice, leading me to working with colleagues on a project with the BBC looking at how Strictly embraces diversity.

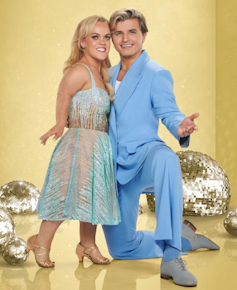

This year’s line-up includes paralympian Ellie Simmonds and comedian Jayde Adams, who are still in the competition, as well as presenter Richie Anderson, who was eliminated in week three.

Simmonds, who was born with Achondroplasia dwarfism, is part of a growing group of disabled celebrities showcasing their abilities in Strictly Come Dancing, (including last year’s champion, Ayling-Ellis, who won people’s hearts with her “silent dance”).

Anderson and Adams are the two contestants in same-sex pairings this year. These partnerships were first introduced in 2020 when boxer Nicola Adams was partnered with Katya Jones, and continued last year with finalists and fan favourites John Whaite and professional dancer Johannes Radebe.

With this year being hailed as the most diverse series ever, Strictly is attempting to better reflect the diversity that exists across the British population by challenging the dominant norms in dance traditions and styles that feature on the show.

The drive towards more inclusivity and representation has been praised by many, not least by communities that have long been underrepresented on television generally, and more specifically, on primetime shows.

As a co-investigator on the Strictly Inclusive project to celebrate the BBC’s centenary, I have been talking to the public about the show. The project collaborated with Coventry Pride, the Deaf Cultural Centre and Deaf Explorer in Birmingham. We also spoke to local artists, analysed archival clips of the series, hosted discussions and reflected on inclusion and representation as whole on the show – past, present and future.

Gender pairings and disability

This push for greater inclusivity on Strictly does not always find support. Developing the format away from the original show Come Dancing (which launched in 1950) has been met with some negative criticism.

Recently labelled as a “woke box-ticking exercise”, Strictly seems to be disrupting ideas of what dance should be and what dancers should look like, as well as expanding what we have come to expect from Saturday night entertainment shows.

Interestingly, Strictly’s first disabled contestant was not on the main show, but a 2015 Comic Relief version. The People’s Strictly welcomed specially chosen members of the public to participate in a one-off series. War veteran Cassidy Little took part and won.

Since then, many paralympians and veterans have embarked on their “Strictly journeys”, working with dance partners and choreographers to adapt movement to best suit their bodies, while attempting to adhere to the rules and expectations of ballroom and Latin dance styles.

Queer culture has long been a part of Strictly’s identity, from its popular judges to its celebration of queer celebrities through costuming and song choice – see Russell Grant’s 2011 American smooth to LGBTQ+ anthem I am what I am.

It seems same-sex pairings were requested and denied for many years. The BBC introduced the idea with the first celebrity same-sex partnership in 2020, ten years after it happened on Israel’s Dancing with the Stars. In spite of accusations of superficial tokenism, Strictly now appears to be committed to genuine sexual representation, ensuring there is a choice in dance partners.

How things change

Diversifying those who participate in reality TV shows can bring pressing issues to a larger audience. On last year’s series, deaf actress Ayling-Ellis spotlighted British Sign Language (BSL) so prominently that there was a surge in searches for BSL courses.

Since being crowned 2021 Strictly champion, she has led a campaign to make BSL a recognised language in public life, championing a bill that was passed by MPs in early 2022.

The actress has spoken of how the fight to get BSL recognised as an official language has been long and hard-won, suggesting that the publicity and reach of Strictly contributed to the success of the campaign. This highlights how the show can effect change and engage new audiences, champion difference and help inform public policy. Televised dance has the potential to change views on sexuality, gender and disability, as well as who can dance.

What’s next for Strictly?

For all the developments and changes, Strictly’s work on inclusion is not done. To avoid claims of “box-ticking”, the show should continue exploring what dance is, who can dance and how it is shared with diverse audiences.

Although Ayling-Ellis’ stint on the programme made a considerable impression, there is still no permanent BSL interpretation provided for the live show, for example. Also, the styles or genres presented on Strictly showcase particular dance traditions while other styles practised across the UK are rendered somewhat invisible to big public audiences due to their exclusion.

By engaging with audiences and the public more through research projects such as Strictly Inclusive, we can understand the impact televised dance can have on communities and wider society. There is more to be done, but this is certainly a step, a twirl and a shimmy towards a more progressive show and audience.

Kathryn Stamp has received funding from the Arts and Humanities Research Council and the BBC.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.