For Stephen King, 2025 has been one of the most prolific years to date in TV and movie adaptations of his works. But one has to ask themselves, why? If you dig past the darkness and gore, the spirits and horror of it all, you can see stories that offer cultural commentary and political parallels to this angry age. King offers anger and darkness, yes, but also hope in every one of these stories. While most were written more than 30 years ago, their retelling feels downright fresh — and their morals and lessons, right on the money.

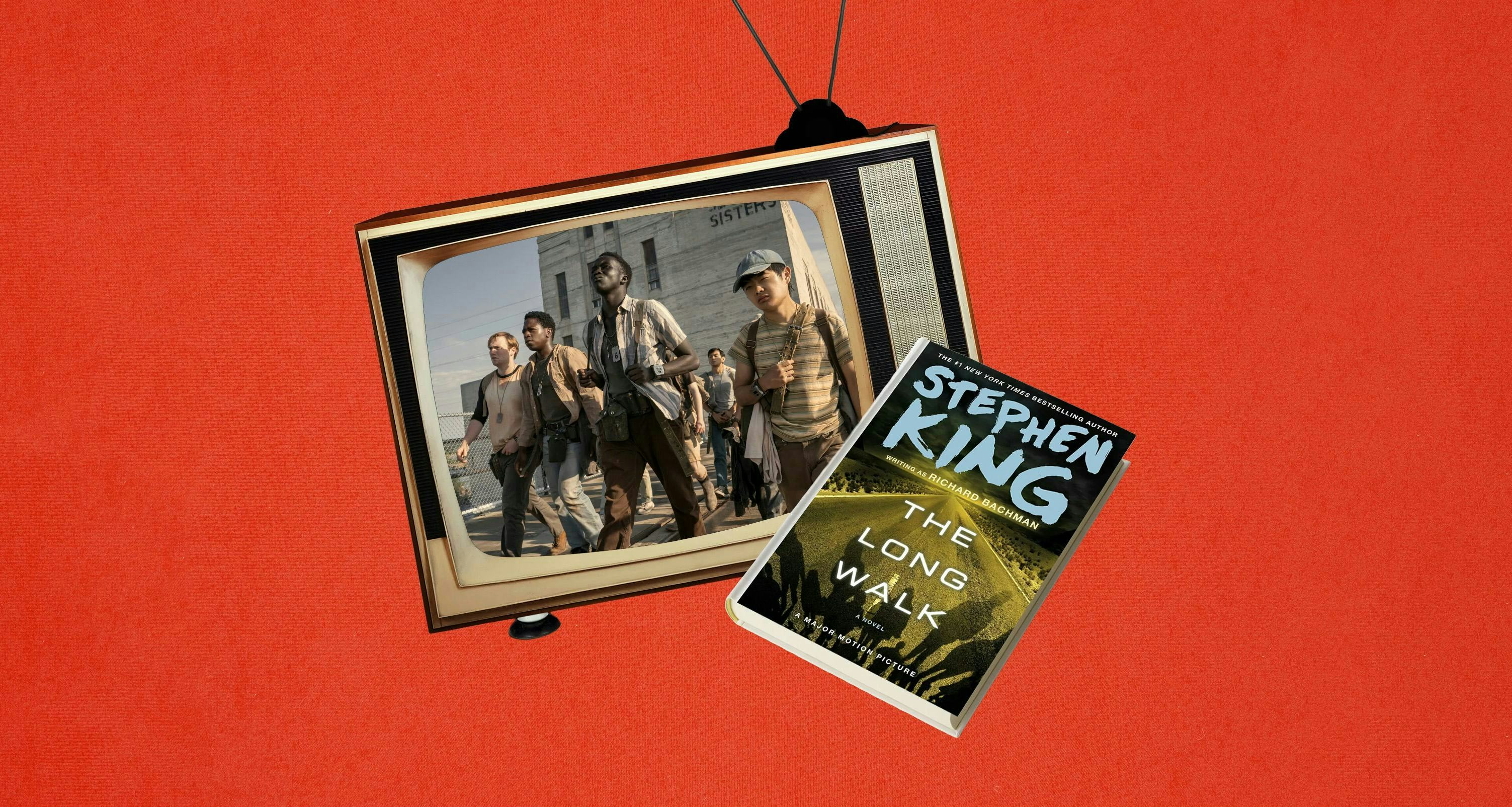

King is going to close out 2025 with four feature film adaptations of his work (The Monkey, The Life of Chuck, The Long Walk, and The Running Man), two TV shows (The Institute, It: Welcome to Derry), and one new novel (Never Flinch).

Osgood Perkins’s adaptation of The Monkey is a silly gorefest about brotherly hatred and revenge that brings a whole community to ruin, and introduces a literal figure of the Reaper on horseback. Mike Flanagan’s take on The Life of Chuck opens with an entire universe blinking out of existence, and both The Long Walk and The Running Man give us a picture of alternate Americas where the power is no longer with the people and instead wielded by giant corporations or authoritarian bureaucracies.

Perhaps that’s why King feels so prophetic this year. Americans are all angry.

Out of all of these projects, The Life of Chuck is the only one written in recent times, published as a novella in his recent If It Bleeds collection. Everything else was written while King was a young man.

The Long Walk in particular is the work of an angry college student so fed up with the authorities forcing the nation’s youth to go fight in Vietnam that he wrote up a story about a militaristic ruler literally murdering young boys in the name of some kind of patriotic competition.

King published both The Long Walk and The Running Man under his pen name, Richard Bachman. He had a few reasons for using a fake name, not the least of which was that his publisher was worried that he’d be overexposed if he released too many books in a year. But when you read his Bachman output, you recognize right off the bat that this is King letting his dark half take over.

Two Richard Bachman Adaptations Showed Different Perspectives On 2025

Without fail, the Bachman books are pulpy, bleak, and leave the reader feeling like they’ve been punched in the gut. Most of the protagonists are morally gray, all of them are angry. The Running Man’s Ben Richards, as written, is a misogynistic, sometimes racist, man of targeted fury. Ray Garraty of The Long Walk comes out the cleanest of the two Bachman protagonists seen in theaters this year, but even he is motivated by revenge.

Perhaps that’s why King feels so prophetic this year. Americans are all angry. Left, right, center, justified or not, this country feels angrier than it has perhaps since the civil rights fight.

The thing is, though, at his core King is a humanist. He grew up poor, first with his single mother holding the family together throughout his childhood, and then later as a hopeful writer trying to keep his young family in food and board by working multiple blue collar jobs and selling short stories (like The Monkey) to gentlemen’s magazines. He relates to the Average Joe and always has compassion for them.

Even when writing under the Bachman persona, a little bit of that Stephen King optimism leaks through. For all the bleakness of The Long Walk, it’s ultimately still a story about a group of young men who band together and support each other through hell even if it means putting their own survival at risk. An apt allegory for our armed forces throughout the years, but also a glimpse at where King’s heart is for his characters. The 19-year-old “damn the man” version of King who first wrote the story couldn’t help but default to these young men banding together instead of tearing each other apart.

Ray Garraty and Peter McVries and their crew watch each other's backs instead of what we’ve been conditioned to expect from decades of reality competition shows, which always turn into a survival of the fittest free-for-all. Every time they help out a fellow walker, that’s one more body between them and victory, but their humanity takes precedence.

King believes in the inherent goodness of people, which is funny when you consider his reputation. He’s the master of horror and the father of Pennywise, after all. I’d argue he’s so good at telling horror stories because he makes you care for his characters and one of the easiest ways to flip that empathy switch is to show the reader that these characters care about other people, too.

Both The Running Man and The Long Walk correctly predicted a lot of things — the former actually being set in the year 2025 despite being written in the early ‘70s and not published until the early ‘80s — and he’s not as far off the mark as he probably thought he was going to be. He thought up reality TV before it was a thing. His view of the future is a dumpster fire in both those stories, but thankfully real life isn’t quite bad enough where I expect desperate fathers will be signing up to be hunted for sport on live TV. Not yet, anyway.

We all contain multitudes.

If I were to guess what King and the many talented filmmakers who adapted him this year would want us to take away from these stories, it's that no matter how bad things get, people are basically good and when given the choice between helping or hurting, they’ll choose to help.

We all contain multitudes, which happens to be the defining mantra of The Life of Chuck. We have good days and bad days, but within each of us is an infinite universe of life and love that is influenced by every other person we’ve ever met, be it a chance encounter or a life-changing interaction.

Be the helper, be the light. It’s the only tried-and-true way of beating back the darkness. That could be you and your friends banding together to fight a shapeshifting monster in the city sewers or simply helping the guy next to you keep his 3-mile-per-hour pace in a dystopian hellscape.

.jpg?w=600)