At a Sept. 4, 2025, hearing before the Senate Finance Committee, Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. faced heated questions from numerous senators about his vaccine policies, including his stance on COVID-19 vaccines and mRNA vaccine technology generally.

Although Kennedy agreed that Operation Warp Speed, President Donald Trump’s signature initiative to produce COVID-19 vaccines in nine months, was a tremendous achievement, he also maintained that COVID-19 vaccines cause widespread and serious harm, including death, particularly in young people – a claim for which there is no evidence.

Some especially pointed questions came from Republican Sen. Bill Cassidy of Louisiana, a physician who provided the final vote needed for Kennedy’s confirmation in February 2025 after Kennedy promised him that he would not change the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s process for recommending vaccines. Cassidy pointed out that with the limitations and confusion caused by the CDC’s new rules around COVID-19 vaccines, “I would say effectively we are denying people vaccines.” To which Kennedy replied, “Well, you’re wrong.”

At the hearing, Kennedy stood by his decision to cut US$500 million in HHS funding for 22 research contracts on mRNA vaccine technology. HHS has said it will instead pour these funds into research on a traditional approach to designing vaccines that was first used more than 200 years ago. With such vaccines, called whole-virus vaccines, a person’s immune system is presented with the whole virus, often in weakened or inactivated form. This switcheroo has puzzled many scientists.

A few days before the hearing, on Sept. 1, Trump demanded that pharmaceutical companies prove that COVID-19 mRNA vaccines work, saying that the CDC was “being ripped apart over this question.” It was his first public acknowledgment of the chaos roiling the CDC amid the firing of its director, Susan Monarez, and subsequent resignations of four high-level agency officials.

Meanwhile, public health experts and HHS staffers are calling for Kennedy to be fired, and several senators at the hearing echoed that call.

As a vaccinologist who has studied and developed vaccines for over 35 years, I see that the science behind mRNA vaccine technology is being widely misstated. This incorrect information is shaping long-term health policy in the U.S. – which makes it urgent to correct the record.

Are mRNA vaccines less safe than whole-virus vaccines?

HHS defended its cancellation of mRNA vaccine research based, in part, on a nonpeer-reviewed compilation of selected publications called the COVID-19 mRNA “vaccine” harms research collection. This document lists about 750 articles claimed to describe harms caused by mRNA vaccines against COVID-19. However, the vast majority of these articles aren’t about vaccines but about the harms of getting infected with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. And notably absent from it is the huge body of data showing mRNA vaccines actually prevent these harms.

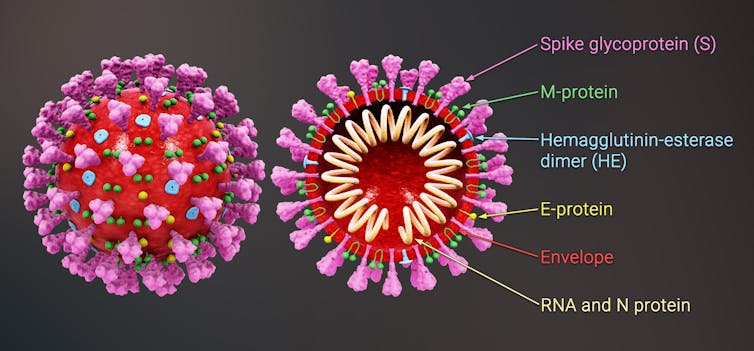

For example, the document being used to justify RFK Jr.’s claims about mRNA vaccines highlights 375 studies reporting that the virus’s spike protein alone, which is produced when the virus replicates, can cause excessive inflammation and tissue damage. This is true. But the document marshals this evidence to support the claim that mRNA vaccines, which are designed to produce spike proteins, cause the same harm – which is not accurate.

While viral replication results in uncontrolled production of a large amounts of the protein, the way it’s produced by the mRNA vaccine is very different. The vaccine produces a small, controlled amount of spike protein inside a few cells – just enough to induce an immune response without causing damage. And by blocking the virus’s replication, it reduces the amount of spike protein in circulation, actually having the opposite effect.

What about side effects like myocarditis?

Early reports flagged a type of heart swelling called myocarditis as a rare side effect of the mRNA vaccine, particularly for young men ages 18 to 25 after a booster dose. A 2024 review identified about 20 cases out of 1 million people who received the vaccine. However, that same study found that unvaccinated people had an elevenfold higher risk of getting myocarditis after a COVID-19 infection than vaccinated people.

What’s more, another 2024 study showed that people who developed myocarditis after vaccination had fewer complications than those who developed the condition after getting infected with COVID-19.

Do mRNA vaccines make the SARS-CoV-2 virus resistant?

Another claim from the compilation of supposed mRNA vaccine harms that was cited as a reason for cutting funding for mRNA technology is that mRNA vaccines cause mutations in the SARS-CoV-2 virus that make them resistant or less susceptible to the vaccine.

When a virus replicates in its host, it produces millions of copies of its genetic material. Mutations are copying errors that occur naturally during the replication process. These acquired mutations produce new variants, which is why both the COVID-19 mRNA and the whole-virus flu vaccine get updated annually – to keep up with natural changes in the virus.

Slowing down viral replication decreases the rate at which a virus can acquire new mutations. Since both mRNA and whole-virus vaccines stop or slow the virus from replicating, both types of vaccines help reduce the emergence of resistant viruses.

Viruses can mutate to escape from antibodies, but the mRNA vaccines are not causing the emergence of more virulent strains, likely for at least two reasons. First, mRNA vaccines induce immune responses that can attack the virus at multiple spots, so it would have to come up with many mutations at once to escape the vaccine’s defenses. Second, even if the virus could acquire all these mutations, they would likely weaken it, making it unable to cause or even transmit disease.

mRNA vaccines versus new SARS-CoV-2 variants

Kennedy, in announcing cuts to mRNA vaccine research on Aug. 5, 2025, claimed that mRNA vaccines don’t work against respiratory viruses and that HHS was moving toward “safer, broader vaccine platforms that remain effective even as viruses mutate.”

Both whole-virus vaccines and mRNA vaccines protected against COVID-19 and prevented hospitalization and death for millions of people worldwide between 2020 and 2024, but there’s clear evidence that the mRNA-based vaccines provided significantly better protection than whole-virus vaccines. And for COVID-19, mRNA vaccines are more effective against new variants, which emerge as viruses mutate, than whole-virus vaccines.

The COVID-19 mRNA vaccines started with exceptionally high efficacy, exceeding 94%. When the SARS-CoV-2 delta and omicron variants emerged in the spring and fall of 2021, mRNA vaccines became less effective in preventing infections. However, they remained highly effective in preventing severe illness, whereas in unvaccinated people the rates of severe illness and hospitalization remained high.

This is because mRNA vaccines induce the immune system to make both antibodies and specialized immune cells called T cells. These elements can recognize multiple parts of the virus, including ones that don’t change, enabling significant protection against new variants.

What’s more, the mRNA vaccines have a superpower that no other type of vaccine can currently match: They can be quickly updated and manufactured within two to three months. To develop a whole-virus vaccine, researchers must first spend months isolating and propagating the virus. Conversely, making an mRNA vaccine requires just sequencing the virus’s genetic code – a process that today takes just hours.

If a new pandemic began today, mRNA vaccines are currently the only type of vaccine that could be developed quickly enough to disrupt its spread.

The future of mRNA vaccine technologies

Thirty years ago, when scientists first started developing mRNA vaccine technology, they recognized its potential to overcome major limitations of whole-virus vaccines – namely, slow production time and more limited ability to protect from new viral variants. Today, mRNA vaccines are also being developed to prevent or treat diseases including HIV and cancer, as well as autoimmune and genetic diseases.

Of course, this technology can be further improved. New mRNA vaccine technologies are aimed, among other things, at making mRNA vaccines easier to store to allow for faster distribution and reduce their short-term side effects, eliminate the rare risk of myocarditis and more quickly block a respiratory infection.

The National Institutes of Health is funneling money away from new mRNA technologies toward a single project developing universal vaccines based on traditional whole-virus vaccine technology. Universal vaccines are urgently needed to provide broader protection against ever-changing respiratory viruses, such as influenza, that are major pandemic threats.

A 2022 study in mice and ferrets showed that a universal flu vaccine NIH plans to support has promise. However, multiple studies of potential universal flu vaccines based on mRNA technology show even more potential. Such vaccines could induce broader immunity than whole-virus vaccines by eliciting antibody and T-cell responses that target an even wider range of flu viruses.

It’s hard to square those benefits with the fact that HHS and NIH have named the planned new universal vaccine platform “Generation Gold Standard,” insisting that it represents a new standard in science and transparency. The effort seems more akin to eliminating all e-bike technology and telling everyone who seeks one to get by with a single brand of a 10-speed bike: Getting to the intended destination may still be possible, but it will be slower and harder.

And in the case of abandoning mRNA vaccine research, it may lead to lives needlessly lost, whether due to potential medicines untapped or to pandemic unpreparedness.

This article was updated to include details from Kennedy’s Sept. 4, 2025, hearing.

Deborah Fuller receives funding from the National Institutes of Health. She is co-founder and a scientific advisor for two biotech companies developing nucleic acid vaccine technologies that are not based on mRNA and that do not benefit from mRNA-based vaccines.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.