The contingent of neo-Nazis arrived at Flinders Street station about an hour before Sunday’s anti-immigration rally was due to start.

A hundred or so men, dressed in black, strode across Princes Bridge in a bloc, weaving through the large crowd that had already gathered under a sea of Australian flags.

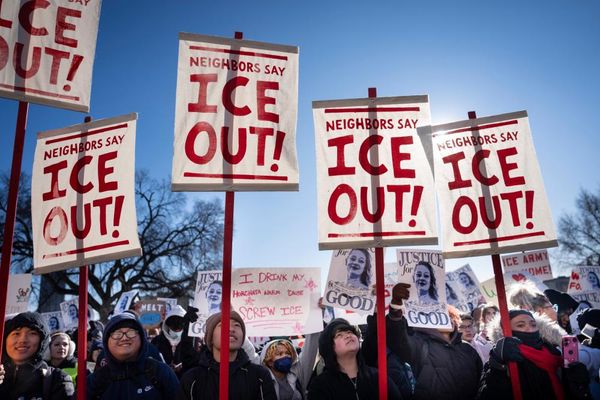

Plenty of people in the lead-up to the so-called March for Australia on Sunday, and many who attended, said that the widespread promotion of the rally by known neo-Nazis did not mean it was organised by them; or that the presence of the National Socialist Network (NSN) in the crowd did not mean it was central to the day’s message.

Even if they were there, some said, you didn’t have to agree with everything they said in order to attend.

In Melbourne, however, neo-Nazis were not just central to the march, they led it, all the way to the steps of parliament. And the NSN leader, Thomas Sewell, when he addressed the crowd to huge cheers, clearly laid out the role he envisioned for “my men” in the “fight for [Australia’s] survival” against “ginormous empires of the third world”.

Members of the group went on to attack a First Nations protest site, Camp Sovereignty, in Melbourne’s Kings Domain on Sunday evening.

In Sydney, too, the New South Wales leader of the group spoke to cheers of “send them back” from onlookers as Australian flags flew in the background. Pamphlets were handed out for a far-right political party about the “plague level” of immigration.

Australia’s immigration figures are not at record highs. The government says the net overseas migration figure is down 37% from a recent peak.

Sign up: AU Breaking News email

In some cities, politicians spoke at the rallies. In the lead-up, parts of the media interviewed march organisers and showed the flyers on television.

“It was only about recruitment,” said Mario Peucker, an associate professor at Victoria University, of the presence of far-right figures on Sunday. “It was an opportunity to mingle with people who basically [are] their target group … presenting themselves as the only voice for them.”

Victoria police said it was too early to confirm whether the attack on Camp Sovereignty or any of the other activity complained about at the rally would be investigated as “prejudice-motivated”, the force’s term for offences that could also be described as hate crimes.

From TikTok to the streets

The first mentions of a “March for Australia” came after the Palestine Action Group’s March for Humanity, when massive crowds (police estimated 90,000 but organisers said the figure was closer to 300,000) walked across the Sydney Harbour Bridge on 3 August to oppose Israel’s actions in Gaza.

Online, the event incensed several high-profile nationalist accounts, one of which made AI-generated images of the bridge covered in Australian flags.

Soon a TikTok video emerged from an anonymous account. Over stock footage of Australian flags, it called for rallies on 31 August: “We finally stand up for ourselves and take this country back.” The clip included footage from the 2005 Cronulla race riots.

A woman who goes by the name Bec Freedom online claimed to be in touch with the video creator, “a young kid”. In early August, she began responding to tweets from One Nation’s Pauline Hanson and various online influencers with a poster calling for Australians “to rise” on 31 August.

In an X space on 11 August (where live audio conversations occur on the X platform), Bec said messaging should follow certain steps: “So, protect Australian heritage, culture, way of life. Next step, protect European culture, heritage, way of life. The next step is protect white heritage. So it all means the same thing.

“By saying it that way, it is more appealing to the public. It’s going to deter them from saying, ‘Oh, it’s a Nazi rally, blah, blah, blah’. ‘Australian’ is white.”

In response to questions from Guardian Australia about the comments, Bec said: “Am I a nationalist? Yes. Am I white? Yes. So I guess I’m a White Nationalist.”

The March for Australia website launched on 8 August and the ABC reported that an earlier version of the March for Australia websites included a reference to the white supremacist concept of “remigration” – the forced return of immigrants back to their country of origin. The ABC report makes clear it had been unable to establish exactly who was responsible for the website.

As the date approached, there was confusion about who the organisers of the rallies were in each state, although statements on the March for Australia Facebook page distanced the events from white supremacists.

“In particular, recent claims by Thomas Sewell of White Australia are not reflective of the organisers nor the politics of March For Australia. We are not associated with their organisation,” it posted on 12 August.

In a video on 22 August, Bec said she and other organisers were not members of any extremist group, and were not endorsing violence. “All we are doing is gathering en masse to fight for Australia,” she said.

The rallies also brought together many elements of the pandemic-era anti-lockdown movement and others, but despite the messaging of the March for Australia accounts, Nazi groups clearly intended to capitalise on the events, with the NSN group White Australia issuing a press release in the lead-up claiming to have “positive ongoing contact with the event organisers nationwide” and promising that members would be speaking at March for Australia events.

Bec said she was not in contact with anyone from White Australia. On the question of whether the marches were sites of neo-Nazi recruitment, she said it was “irrelevant to myself or March For Australia”.

“I can’t comment on what took place in Melbourne, as I publicly withdrew from any organisation of the event,” she said. “But no, they [the NSN] were not invited to speak at the Sydney event, they took part in the open mic section after the designated speakers.

“The March For Australia events were for all Australians, no one was banned from attending.”

She said there were plans for future events.

British protests and Trump raids

The rallies come amid growing anti-immigration protests in the UK as well as the Trump regime’s raids and deportation of migrants.

These ties were recognised in March for Australia messaging, with the main account posting on Instagram in support of Operation Raise the Colours. This movement urges members to raise British flags around the country and post photos, and the 31 August events in Australia was praised in turn by British “patriot” accounts.

Aurelien Mondon, a UK-based academic who attended the recent protests there, has written extensively about how immigration is often used by those on the far right to appeal to the mainstream.

He also says it is important not to describe such movements as “populist”, even when they involve the support of politicians.

“When we allow the far right to be described as populist, we are incorrectly implying that they are tapping into what the people want or that they speak for the ‘silent majority’,” Mondon and a fellow academic, Alex Yates, wrote in a piece for the Conversation last year.

In February, Mike Burgess, Asio’s director general, used his annual threat assessment to outline the spectre of the far right. “We expect nationalist and racist violent extremists to continue their efforts to ‘mainstream’ and expand their movement,” he said.

“They will undertake provocative, offensive and increasingly high-profile acts to generate publicity and recruit.

“While these activities will test legal boundaries, the greatest threat of violence comes from individuals on the periphery of these organised groups.”

Rallies represent a new escalation

There was a range of grievances on display about perceived immigration rates on Sunday, but it was clear for many that the return to an imagined white Australia was a central theme.

For Jordan McSwiney, who researches the far right at the University of Canberra, the weekend’s rallies brought to mind the 2015-17 anti-Islam and anti-immigration street protests of Reclaim Australia.

This time, however, far-right groups were not shielding their involvement.

McSwiney noted how “easy it has been for the NSN to basically use the shield of ‘ordinary mums and dads’ to sell white supremacy to a big crowd of people who may very well have genuine concerns … that won’t be fixed by stopping immigration.”

In his view, the recent response of state and federal governments to these movements – banning known Nazi symbols, for example – has been a distraction, and has not made it meaningfully more difficult for neo-Nazis to organise and recruit in Australia. As has been the “softball condemnations” of some politicians in response to the rallies – and the presence of others.

For Peucker, Sunday’s rallies represent a new escalation that demonstrated how the views of some who consider themselves “part of the ordinary Aussie mainstream” overlap with the political agenda of openly white nationalist groups.

“It’s not that white supremacy, which was present clearly yesterday, is something that the neo-Nazis in some evil, secretive fashion introduced into the political mainstream,” Peucker said. “It is something that has always been present in parts of the mainstream.”