The email came from a stranger. “Dear Mr. Temple,” it said. “My name is Andrea Paiss, and I live in Budapest, Hungary. I do not know whether I write to the right person. I just hope so.”

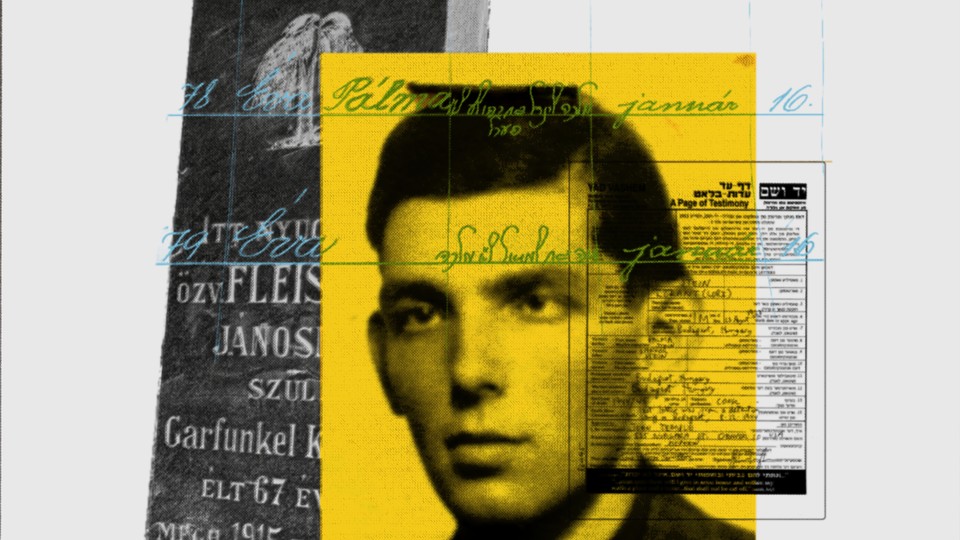

It reached me in San Francisco on January 1, 2020, and told of a “Granny,” then 92, who wanted to know what had happened to her cousin Lorant Stein. Andrea had found a document online about Lorant in the Central Database of Shoah Victims at Yad Vashem, the Holocaust memorial in Jerusalem. It had been submitted by someone named John Temple. Could I be that same John Temple, she asked, the one who had filled out the form by hand 20 years earlier? “I would be happy if you could tell me how you [are] related to Lorant, as we have no information about relatives in America.”

At first my wife, Judith, and I were mistrustful. Could this be an attempt to get money, a scam of some kind? I had filled out the form, but I had no information about relatives still living in Hungary. The last, I thought, had been two sisters of my grandfather who died years ago.

When I was a boy, my family was small: my parents, my mother’s parents, and my older brother. That was it. My father’s mother lived alone in Vienna, and died when I was 10. His father had died in 1945. Growing up in Vancouver, British Columbia, in the 1950s and ’60s, we were different from my friends’ families. Unlike their parents, mine were immigrants, from Austria and Hungary, who spoke English with heavy accents. They also spoke Hungarian and German. They ate chicken paprikash and goulash, not hamburgers and hot dogs. All the same, they wanted us to fit in, starting with the vanilla names they gave us: Chris and John.

We were to be of the New World, not the Old.

Before receiving the email, I couldn’t recall ever meeting anyone other than my parents and grandparents who had known my uncle, Lorant, my mother’s brother.

Andi, as Andrea calls herself, told me that her Granny, Magda Gardonyi, remembered Lorant fondly. She still recalled vividly the last day they had arranged to meet. It was December 6, 1944, during the worst period of World War II in Budapest for Jews. Lorant never showed up. After that, she said, she never heard from him again. Now, more than 75 years later, she had asked Andi to try to find out what had happened to him. Magda didn’t know that Lorant had been arrested by the Germans two days later. That, along with almost 2,000 other Jewish men, he had been transported from Budapest to Buchenwald, the concentration camp in Germany where, on December 25, 1944, he became Prisoner No. 32317.

When I filed the form at Yad Vashem, I didn’t know those facts either. My parents always told me they had tried everything to learn his fate, to no avail. But the internet has made many records more easily discoverable, and as a journalist, when I had some time on my hands I would occasionally search for him. In 2013, a year before my mother died, I discovered his fate.

In our first video call, Magda’s long face and deep smile seemed familiar to me. I told myself she looked like family. She had shelves stacked with books behind her, just as I did. She told me things I had never heard about Lorant. She recalled how he would visit her family with my grandfather every year after his bar mitzvah, during the High Holidays. High Holidays? I didn’t know they had been part of the rhythm of my family’s prewar life. Bar mitzvah? I didn’t know that Lorant had even had one.

I felt I had to explain why I couldn’t speak Hungarian. It would have been so much easier to talk with each other if Andi didn’t have to translate for each of us. I told them that when my parents had come to Canada, they’d wanted their children to be free of the past, that they had wanted to start new lives.

That must have sounded strange to Magda. She still lived in the same apartment where her cousin and his father—my uncle and my grandfather—used to visit her 80 years before.

My parents never told me we were Jewish. I discovered it as a teenager. A psychiatrist born in Vienna hit me with it one day when I sat down in his office in my hometown in Canada. He said, “You are Jewish.” I was stunned. Although why, I’m not sure, given all the signs around me.

I went home and confronted my mother and father. We talked in the kitchen. Argued. They didn’t see themselves as Jewish. They saw “Jewish” as a label that others—the Nazis—had branded them with, not who they actually were. I didn’t understand. I was confused. It would take me more than 40 years to confirm that the psychiatrist was right.

My mother, Eva, had gone to a renowned Protestant school in Budapest, the same one the heroic Zionist Hannah Szenes attended, a year or two behind my mom. My mother’s parents sent her there because they wanted her to get the best education. They didn’t practice any religion, to my knowledge. My mother deeply mistrusted any group identity. My father, René, was anti-religious. He grew up in Vienna, and witnessed the city embrace the Nazis in 1938, something that wouldn’t happen in Budapest until six years later. His father moved the family to Hungary because he thought it would be safer for his wife and son. In Budapest, my mother told me, she never wore the yellow star when Jews were required to do so. She never joined her parents in what was known as the city’s International Ghetto, where they and many other Jews were forced to live in overcrowded apartments. Instead, she resisted, joining an underground cell using false identity papers, under the name Fazekas Erzsebet. With her blue eyes and blond hair, she pretended she was from Transylvania and rented apartments that were used to hide people from the Nazis.

My parents had longed for a better world than the one they had known under Nazi occupation. But the reality under a corrupt Communist government after the war was so miserable, they couldn’t stand it. In 1946, seeking personal and political freedom, they fled to Vienna, hidden in an oil barrel on a Russian army truck. (Under Soviet rule, they weren’t permitted to leave legally.) In 1948, they went on to Canada, and kept going as far as they could. To the end of the line: Vancouver, the last stop on the country’s transcontinental railway.

They knew they never wanted their children to experience the same nightmare, and the one sure way to do that, they thought, was to put an end to anyone being able to label them Jewish. My father knew his wife was Jewish but she didn’t see herself that way. My mother told me she didn’t even know my father was Jewish until years after arriving in Canada, when they visited an aunt in the United States. He had hidden his mother’s Jewish family from his own wife. He hid them from me, too.

Before I visited Vienna for the first time, in 1978, he told me about the tomb of his Catholic father’s family, in the city’s central cemetery. But he spoke of no other graves I should visit. He proudly encouraged me to see the bust of the most famous member of his family at the university in Vienna. But he didn’t mention where that person and many other ancestors were buried—the Jewish section of the central cemetery.

The past. Forgotten. Or at least a key part of it. That’s the way they wanted it.

My engagement to Judith, in 1983, was when things came to a head. We asked a Conservative rabbi to officiate our wedding. He congratulated us and asked for our mothers’ Hebrew names. Judith could answer. I couldn’t.

All I knew, I told him, was that my grandmother, when I had shown her a picture of the Dohany Street Synagogue after my first visit to Budapest, in 1978, had exclaimed, “That’s where we got married!”

I had been shocked. She had never given any indication of having participated in Jewish life, except as a very young girl, when she lived with her father’s mother. She recalled the prayers she’d heard in the house. The Iron Curtain was still up when my grandmother cracked the wall of secrecy—I could find no way to verify what she had told me. As a result, the rabbi said he couldn’t marry us in a Jewish ceremony. I was taken aback.

A couple of years after being told of my origins by the psychiatrist, right after I graduated from high school, I had worked to save money, then went to Israel on my own. I spent six months studying Hebrew and working on a kibbutz in the Galilee. I saw myself as Jewish. But I understood the rabbi’s perspective. Under the Jewish law of matrilineal descent, I couldn’t be considered Jewish, because I had no proof that my mother was Jewish. The rabbi told me I could convert. And that’s what I chose to do. Why not affirm it, make it official? In the spring of 1984, I formally converted to Judaism.

When we were married that summer, my grandmother still hid that she was Jewish. My grandfather was already gone. My father, who had hoped to end the cycle of persecution against our family, cried under the chuppah. I’m not sure whether from sorrow over my decision to embrace our Jewish identity or from joy. I like to think the latter.

Then, nearly 40 years later, Zsofia Heeger, a Budapest genealogist who helped Andi find me for her grandmother, quickly pierced the wall. Less than two weeks after I received Andi’s email, Zsofia found my grandmother’s 1900 birth record; as was the practice at the time, it noted the religion and age of the mother: “Jewish—23 years old.” Not only that. She found that the name I knew my great-grandmother by was not her given name. It was not Margit Fenyvesi. It was Maria Fleischer, the daughter of Juda Fleischer and Katalin Garfunkel, from Jarosław, now in Poland.

The picture was starting to become much more clear. But I still couldn’t answer the Vancouver rabbi’s question: What was my mother’s Hebrew name?

This past June, I went to Budapest seeking answers—two and a half years after receiving Andi’s first email. By then, we had lost Magda to COVID. She died before I could ever meet her in person. But we had found at least 36 relatives for a family reunion, cousins from the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, and Hungary. The oldest was 85; the youngest, 5. The small family I had known as a boy had suddenly grown.

My memories of the city from 1978 were gray, dark. I remembered a friend of my grandmother’s closing her curtains when I visited. She didn’t want her neighbors to see that a foreigner was there, because it would raise questions. I remembered the bullet holes in the walls of buildings. And I remembered the sorrow of my grandfather’s sisters, the tears over a son with my same name who hadn’t come back from a labor camp.

This time I arrived not in a cold train station that had filled me with dread, thinking of the railcars hauling Jews out of the city to their destruction. No, this time I arrived in a bright and airy modern airport, where a massive video screen at baggage claim promised nighttime carousing in a vast pool at one of the city’s many spas.

I was greeted warmly by Andi, a striking, tall, blond woman wearing a necklace with Jewish charms—a Star of David and Hebrew letters spelling the word life—and her ebullient young daughter. That day I kept pulling a leather-bound notepad out of my back pocket to scratch impressions. “Thinking a lot of my parents and grandparents. Wish they could be here with me,” I would write this simple sentiment many times over the coming days. There was so much I wanted to ask them.

That night we saw a city I had never seen. Lively tree-lined streets, with outdoor restaurants overflowing with people. Not the cold gray of winter and empty shop shelves I had experienced years before. After dinner, we walked past Lorant’s last known residence, St. Istvan Park 4. The apartment building had been in the International Ghetto, where the Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg had designated a number of buildings as under his protection. Jews there thought that they would be safer, with papers from Sweden and other neutral states. This proved to be only partially true. Anti-Semitic Hungarian fascists brazenly seized Jews from the International Ghetto, dragged them to the nearby Danube, ordered them to remove their shoes, then shot them to death.

After Judith and I said goodbye to Andi and her family, we headed home along the riverbank. It was the kind of summer night when couples and small groups of friends linger, carefree. We were walking and talking, sharing our impressions, when suddenly we stumbled on some small objects next to the river. They were shoes. We realized that we were standing among the bronze shoes of the memorial to the thousands of Jews shot here, a reminder of why so many like my parents had chosen to get as far away as possible from this place. But while I was in Budapest, I still had work to do.

It’s hard to overstate the size of the Kozma Street Jewish Cemetery. Imagine a place the size of 200 soccer fields, with several hundred thousand graves, dating back to the 1890s. Budapest before the war was a major Jewish center, with hundreds of thousands of Jewish residents. Today the community is a fraction of that size, but the cemetery is still used.

It was here, in green fields overgrown with vines and other foliage, that I first went to search for my family’s past, together with Judith, my son Ira, Andi, Zsofia, and her husband, Bence. First we visited the grave of Andi’s Granny, Magda, the source of our newfound family ties. Hers was still an earthen mound, fresh, with no stone yet marking it, near the graves of Andi’s father and grandfather. We held tight to each other.

It’s one thing to look at images of old records online, and another to be standing in the quiet calm of a cemetery, the stones serving as reminders of a community mostly long gone. They have a stubborn presence, even covered in vines. Each, a story. After Andi left us, we ventured deeper. The burrs and thorns from the underbrush wouldn’t be removed from our shoes and clothing for weeks.

Map in hand, Zsofia guided us in the sticky heat to the grave of Katalin Fleischer (née Garfunkel), the furthest back I could go on my mother’s matrilineal path. Wrapped in ivy, but still in good condition, the stone rose from the fertile forest floor. Zsofia worked her magic to make the letters carved into the stone emerge, scraping shaving cream across its surface. And there it was, from 1915, more than 100 years ago, still clear as day: her Hebrew name, Gitel bat Rachel. It was impossible to look away. The proof I had been seeking was etched in stone.

We had lost Magda, but her family still had her apartment, the apartment where she had grown up with her grandfather. This was the apartment where she had first Skyped with me. The apartment where she said my uncle, Lorant, and grandfather Sandor had visited during the High Holidays.

The building seemed like many others in Budapest, with its solid door onto the street. Except for one thing: a small black swastika newly spray-painted next to the door, under the list of names of people who lived in the building. A sick feeling came over me. But I didn’t want to spoil the moment. Andi just shrugged.

The apartment still felt lived-in, even though it had been many months since Magda’s death. Books still filled the shelves. Pictures of loved ones in happy times were posted near her computer. We felt her absence, and expressed our wish that she could have been with us, our sadness that we were too late. And finally, we took pictures of ourselves together in the one place we knew with certainty that my uncle and grandfather had visited more than 80 years ago.

There were no traces of Lorant in the apartment, but Andi’s mother knew where we could find them. She works for the Federation of Hungarian Jewish Communities in Budapest and had arranged for us to visit its archive and view his original birth record, along with other family records.

Remarkably, in 1978, I had walked by this building where the truth of my family history was stored. But I had not known what was inside, and I had not tried to enter. Now, 44 years later, I had returned. The archivist had found the correct page for each record and marked it with a sheet of paper. In this room, the facts were plain. There was no denying them.

In my grandfather’s birth record from 1887, what stood out to me was that under his name, Sandor, was his Hebrew name, in Hebrew script, a name I had never heard before: Yehoshua. I had thought his father, Lipot, a printer by trade, had left religion behind. This was to be the first of many surprises. Then we saw the 1920 marriage record of my mother’s parents, and the place of their wedding: Dohany Templom, or Dohany Synagogue, just as my grandmother had told me all those years ago.

Then came my mother’s 1921 birth record: Eva Palma. I hadn’t known that for her middle name she carried her own mother’s unusual name. But what was more startling was the field in the document to the right of her name. Here was her Hebrew name. The answer to the question the Vancouver rabbi had asked me 40 years before: Malka Shindel bat Yehoshua ve Perel. She had a Hebrew name. If only I had known. I could have asked her whether she knew she had a Hebrew name. Whether she had ever used it. Whether she knew where it came from.

I knew my grandfather Sandor was not a religious man. But here, at the birth of his first child, he had given her a Hebrew name. Not all the other children’s birth records on the same page included a Hebrew name. But for Eva Palma, there it was. With tears in my eyes, I explained to the archivist that I had converted to Judaism because I hadn’t known, or at least hadn’t been able to prove, my mother’s Jewish identity. And yet here it was, in black and white, in a building I had stood near 40 years earlier, before my wedding, long before my mother died. Now I could no longer ask her questions.

The archivist was unmoved. In Hungarian, she told Andi, “All the Americans say stuff like that.” Hers is a room where, apparently, mysteries are often revealed.

I wrote to Rabbi William Lebeau, who’d overseen my conversion and with whom I had stayed in touch, to tell him about my discoveries. “As I think I must have said to you, one becomes Jewish by being born of a Jewish mother or by conversion,” he responded. “The status of a person via either path is a Jew with equal status one to the other. Your Jewishness was always equal to my own … Your having gone through an unnecessary conversion is a great opening to your Jewish story, but the revelation of the conclusive proof of your birth origin takes the story to a wonderful conclusion.”

That was how I felt. No regrets about the conversion. It had set Judith and me on a shared path and strengthened our bond. But now I was no longer the son of Abraham and Sarah, the name all who go through conversion are given. So who was I? What was my Hebrew name?

The answer came in my exchange with the rabbi, in response to my question about whether I could now use my Hebrew name to tie myself to my own family. “You can/should,” he replied.

From the time I was a teenager, I had felt that something had been lost because my family’s Jewish past remained hidden from me. Here, in Budapest, I understood better that it may have been done with the best of intentions: to prevent my brother and me from suffering anything like what my family had experienced and witnessed in Hungary. I believe that the best way to respond to our history, to honor those who have been lost, is to connect the generations, not to allow the chain of generations to be broken.

Now I would do so with my own Hebrew name.

“When called to the Torah and for any other time [that] using the Hebrew name is required, you are to be known as Yonatan ben Reuven ve Malka Shindel,” Rabbi Lebeau told me. The stories of Jewish families and individuals are complex, he wrote. The Shoah, or the Holocaust, and the anti-Semitism that endured before and after the war shaped those stories and how we understand ourselves today. Mine is just one story, and it is not unique. Jewish history is filled with stories like mine.

It turned out that of the 29 Steins who attended the reunion, only one cousin, his four children, and my oldest child, Ira, had been raised Jewish from birth. Being Jewish had been a secret for many of us. The secret for some. Known, and to be kept private, for others. At best, little discussed. Until Andi’s email, it had been easiest to keep it that way.

By the end of the trip, we had much cause for celebration. A family cast asunder by the Second World War had reunited. Some whose direct ancestors had left Europe long before the war and believed those who remained had been lost. Some who’d left after the Shoah to start new lives in new worlds and had lost touch with those who remained. And some who’d stayed and never knew about the lives of family members in distant lands. We had been lost to one another. And now it felt like we had been found. “I don’t think this is the end,” my new American cousin Lisa Stein told the group, gathered at a hotel in Budapest for our final dinner. “I think this is the beginning.”

“Next year in Jerusalem!” one of her sisters responded. Many in the group emphatically repeated those words, just as we do at the end of the Passover seder. I could never have imagined, when Andi’s email arrived asking about my uncle, Lorant, that it would result in this.

But there was one more step I had to take.

A journey that started with a question about Lorant’s life needed to end where he’d died. No one from my family had been to Buchenwald since the war. The camp is only five miles from Weimar, a cultural capital of Germany, home of the writers Goethe and Schiller, home of the Bauhaus.

It was there, in a charming city of large trees and stately houses, that I first saw the name Buchenwald. It was on a bus sign, announcing its destination, just like any other bus sign does. I was shocked by how ordinary it seemed.

We arrived at the camp on a gray weekday. The sprawling parking lot was almost empty. Few visitors were in sight. On the surface, it seemed much like many other tourist sites: a cafeteria, restrooms, and a bookstore. But I wasn’t prepared for what I would find. There’s no way a person can be.

Not for its sheer scale. Not for its emptiness. Not for the birdsong or the grass waving in the wind or the trees, the trees everywhere. Not for how peaceful it seemed. Or for the grim facts presented so starkly. We were met by Jan Malecha, a guide deeply knowledgeable about Buchenwald who had done research into Lorant’s two and a half months there. The Nazis kept detailed records of each prisoner. Some things we can know. Some we can only imagine. We knew this was where his life had ended. We could only imagine, with the help of Jan, what he and others had experienced.

We walked to where the train carrying Lorant would likely have arrived. Followed the path he and the other 1,912 Jewish men from Budapest on his transport would have tread. We saw the brick crematorium etched against the gray sky. Jan told us about the German company in the nearby town of Erfurt, a place where Jews had lived for at least 1,000 years, that designed and built the crematorium ovens for Buchenwald, capable of consuming 300 bodies in a day. The firm had done the same for Auschwitz and Dachau.

Buchenwald was good business for many. It was a place for profit. The forested hilltop was visible from a great distance, and its subcamps were spread around the region. Prisoners sometimes marched through the streets of Weimar from its train station to Buchenwald even after the Germans forced the prisoners to build a rail line to the camp. The camp was no secret to the local residents.

Lorant was initially confined in a tent in the infamous “Little Camp,” of which almost nothing remains, except traces of the latrine and fruit trees probably planted by the Nazis to supply food for the SS. The language that present-day Buchenwald uses to describe the Little Camp, also known as the Jewish Camp, is unflinching: “Conditions were barbaric. Windowless stables with dirt floors intended to house 50 horses at times contained nearly 2,000 people. There was no running water, no sanitation, and virtually no heat in the stables.”

A cold wind whipped across the grass as we walked. The Little Camp—out of sight of Weimar—was where the conditions were the harshest, the coldest, Jan told us. In the first 100 days of 1945 alone, 6,000 inmates died there of starvation. Over that same period, the Nazis deliberately killed sick, weak, and dying inmates in Block 61 of the Little Camp, according to one of the signs. The camp was “the place of deepest despair” at Buchenwald, as it is described there today. After the war it was “totally obliterated and allowed to be overgrown with trees and brush.”

Jan told us that on December 30, 1944, Lorant had been taken to one of the subcamps, Berga/Elster, about 60 miles away. He was held there until the end of February 1945. By then, Budapest, his home city, had already been liberated. His family was already safe. At Berga/Elster, Jews were forced to do the heavy, dirty work of removing rubble after explosions blasted tunnels into the mountain. The Nazis’ plan was to build a synthetic-oil plant that would be protected from Allied bombers. Eventually Lorant was transported back from Berga/Elster back to the Little Camp; why and how is not known.

We know Block 61 was where Lorant died, on March 14, 1945. We know that this was the site of mass murder, where Nazis injected Jews with phenol and then lied about their deaths. We’ll never know whether Lorant died of dysentery, as his death report says, or whether he was injected with poison. We do know he was 21 years old.

We also know that accountability after the war for the crimes committed at Buchenwald was almost nonexistent. Nine thousand people worked there. Only 79 were ever convicted for what they had done. Fifty-six thousand prisoners died.

Lorant’s body, we were told, was buried in one of several mass graves—one of thousands of prisoners buried there. Standing so close to where he was buried, so close for the first time, I felt I could talk with Lorant. You are not forgotten, I said. I wanted him to know that his name alone had brought strangers together as family. The Steins. From the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, and Hungary. Even 80 years later, even with all who knew you gone, I told him, you live on.