Jake Barnes is an American newspaper correspondent working in Paris in 1922. Cohn, a friend who wanders around. Brett, the beautiful divorcee who has turned the French capital into a platform between two trains. Mike, the promise of a husband she has procured in the meantime. And Bill, a friend of Jake’s who only seems to think about fishing.

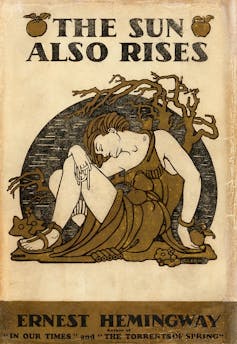

Ernest Hemingway brings together all of them, and the bullfighter Pedro Romero, a transcript of the Niño de la Palma, in the Pamplona of The Sun Also Rises (1926).

The novel unfolds amid the Sanfermines, the legendary fiesta that celebrates the co-patron saint of Navarre, Saint Fermín, son of Firmo, a Roman officer Christianised around the 3rd century by Saint Saturninus, Bishop of Toulouse. According to legend, Fermín settled in Amiens and died a martyr’s death, his throat slit. Oral sources declare that the red pañuelico (scarf) worn around the neck on feast days is reminiscent of his fate.

Origin and history of Sanfermines

The history of the Sanfermines would take too long to recount. Over the centuries it has undergone many changes. Between the 14th and 16th centuries, there was a change of dates so that celebrations that once took place in the autumn were rescheduled for the solstices and finally moved to the summer. The ritual of the txupinazo, the explosion of a rocket that starts the fiesta, was devised at midday on the 6th of July 1939.

The best-known part of the feasts is the encierro, the 8 a.m. journey taken by the six bulls that are going to take part in the afternoon bullfight. This starts at the stable and ends at the bullring, crossing the old quarter of Pamplona. In the olden days, the bulls were led by the ranchers. The current tradition of running in front of the animals until they reach their destination has been preserved from this custom.

But this isn’t the only tradition that occurs during the Sanfermines. Among the many traditions that surround them are the mass and procession of Saint Fermín, patron saint of Pamplona and Navarre, the encierrillo – in which every day at 10 p.m., the bulls that will take part in the encierro the following morning are taken to the stable – or the riau riau, a popular celebration in which the citizens sing and dance a 19th-century waltz, occupying the streets of the centre and blocking the way of the municipal corporation. The riau riau has been absent from official celebrations for several years, although it continues to be performed unofficially.

The Sanfermines are an amalgam of Christianity and paganism. Hemingway was able to see that instantly. The bullfight, he states in his novel, is “a tragedy in three acts”. Later, however, he observes that “San Fermín is also a religious festival”.

In fact, it can be said that it is precisely Hemingway’s literary recreation of the Sanfermines that shaped what we know today. A glance at the novel is enough to prove it.

Pamplona was a moveable feast

There are several themes in The Sun Also Rises. The first is Jake’s drama: his impotence, caused by a war wound, is underlined by the irony of Brett’s preference for him among the men who want her (Mike, Romero, Cohn) and by the exaltation of virility that the bullfighting festival represents.

Another underlying theme is the mood, which makes The Sun Also Rises an emblem of what Gertrude Stein called the “lost generation”, traumatised by the First World War. In fact, it was Stein who advised Hemingway to visit the Sanfermines.

Jake’s wound thus invites a symbolic reading, and points to an evil that is not exclusive to him. The book suggests that, like Ulysses, this group of Americans are reluctant to return to their homeland after the conclusion of a war that has overturned all their certainties. Behind the visible hunger for action lurks ennui.

A third theme has to do with Hemingway’s personality. The writer was someone who not only wrote about adventure but turned writing itself into it, someone who liked to hunt crocodiles in Florida, fish for tuna in Cuba or shoot wild beasts in Africa.

That is what the characters seek, a binge of adventure and exoticism with three obvious manifestations: the aforementioned sexual tension, bullfighting and drinking. It should not be forgotten that The Sun Also Rises is written during Prohibition and that the author comes from Chicago, a city that has become the centre of the illegal liquor trade.

In contrast to that dilemma between abstinence and drunkenness, between illegality and puritanism, what these North Americans find in the Sanfermines is a festive and joyous experience. They drink publicly, without remorse and with joy.

Hemingway and the Sanfermines

The Sun Also Rises wasn’t the only thing that Hemingway wrote about Pamplona. In October 1923, he had published the article “Pamplona in July” in Toronto’s Star Weekly, after his first visit of an eventual ten. He would later mention the fiestas in Death in the Afternoon, 1932, his book on bullfighting. It was, however, his consecration as a writer… and the universal consecration of the Sanfermines (despite the fact that most of the novel does not have this fiesta, but Paris, San Sebastian, Bayonne and Madrid, as its setting).

Hemingway was able to see this for himself after a long hiatus. During the 1940s he was unable to visit Pamplona (he had spoken out in favour of the Republic and written For Whom the Bell Tolls, a plea against the policy of non-intervention), but when diplomatic relations between the United States and Spain were re-established, he did not have time to take the plane.

What he found was something of a boomerang: instead of the local party in a small town, he now saw the cosmopolitan tumult brought about by the popularity of his own novel (and of the 1957 film adaptation made in Mexico by Henry King).

In short, life imitated art: the feast was now a crowd of foreigners eager to emulate the adventures of Jake, Mike and Brett in a sort of theme park. The local population, meanwhile, had added to the traditional red pañuelico, with a uniform of white shirt and trousers that was only really seen in King’s film – the kitsch logic of those who wish to confirm a postcard peculiarity for the outsider. And, of course, the more pagan side was beginning to prevail over the religious.

Gabriel Insausti Herrero-Velarde ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d'une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n'a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son organisme de recherche.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.