Northern Territory Coroner Elizabeth Armitage’s inquest findings into the death of Kumanjayi Walker have sparked conversations across Australia.

The coroner found the NT police officer who shot Walker, Zachary Rolfe, was “racist”, and she couldn’t exclude the possibility that his “values […] contributed to his decision to pull the trigger”.

For many, the findings have raised questions about the history, role, purpose and limitations of coronial inquests. So what are they, and what do they do?

What is a coroners court?

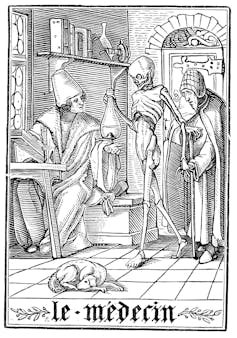

The office of coroner emerged in England in 1194. Coroners were powerful officers of the realm – collecting taxes, adjudicating treasure troves and investigating deaths.

During the industrial revolution, they became known as the “Magistrates of the Poor”, holding governments and corporations to account for causing sudden, unnatural or violent deaths.

In the 21st century, each state and territory in Australia has its own coroners court. A coroners court consists of a state coroner or chief coroner, who is the equivalent of a judge, and other coroners, who hold the position of a magistrate (beneath a judge in the court hierarchy).

All coroners are legally trained. In the 19th century, all coroners in Australia were doctors. There is no longer a requirement for coroners to have medical qualifications.

Coroners investigate unexpected, unnatural, violent and accidental deaths. In Victoria, for instance, this is about 7,400 deaths each year.

Legislation requires coroners to determine the who, when, where, what and how of such “reportable” deaths.

This means they need to determine the identity of the deceased, when and where that person died, what caused their death, and the circumstances or manner in which they died. In many instances, they make recommendations for reducing preventable deaths in the future.

Police help coroners in their investigations by providing a brief of evidence, but the coroners court is separate from the police, just as other law courts are. Forensic pathologists assist coroners in finding the medical cause of death.

Read more: What happens in an autopsy? A forensics expert explains

Since 2005, first in Victoria and then elsewhere in Australia, forensic pathologists and radiologists have used postmortem CT scans to determine cause of death. This has greatly reduced the need for invasive autopsies.

Coroners can make findings “on the papers” – which means investigations won’t proceed to an inquest – or deliver findings at the conclusion of an inquest.

So what is a coronial inquest?

A coronial inquest is a formal public hearing into why someone (or sometimes a group of people) died. It’s often held across multiple days, during which the facts can be examined, witnesses can be questioned, and the community can come together to understand how a person died.

What is unique about the Coroners Court is that it’s inquisitorial, not adversarial. This means there shouldn’t be any warring parties.

In addition, inquests have an expansive scope compared to a criminal trial. They can investigate the wider institutional, social and economic contexts of a death, examining what may have contributed to it, and comment on factors connected to the death, such as public health and safety.

Not all investigations proceed to an inquest. In fact, the number of inquests across Australia has been steadily declining since the early 2000s. In New South Wales there were 142 held in 2013 and only 103 in 2023. This is despite the number of investigations over that period increasing by 37%.

The former Deputy State Coroner of NSW, Hugh Dillon, cites a lack of funding, delays due to backlog, and structural design flaws as some reasons for the decline in holding inquests into reportable deaths.

Juries were a feature of inquests in Australia in the 19th century. They were no longer compulsory in the early 20th century, and were formally abolished in NSW in 1999.

Coroners must hold an inquest in certain circumstances. For example:

where the deceased was in custody or care immediately before death

where the identity of the deceased is unknown

or where there is suspicion that the death was due to homicide (though in this situation an inquest will most likely be superseded by a criminal trial).

Coroners are prohibited from making findings of guilt or liability. The purpose of the investigation is to issue findings of facts about unnatural deaths, not to determine questions of law.

Researcher Rebecca Scott Bray points out that coronial proceedings have the potential to be positive experiences, especially for grieving families.

But these processes can fail to live up to that potential, particularly with respect to inquests into deaths in custody.

Why does all this matter?

There is little understanding of the purpose of the Coroners Court in Australian society. More research is required to ascertain why this is the case, but even law graduates have a low level of literacy about the powers and limitations of coroners. They are seldom taught about the coroner in law school.

This results in misunderstandings that coroners can find someone guilty of causing a death, or that coronial recommendations for preventing similar deaths in the future must be implemented.

It isn’t mandatory, for instance, for the NT government to implement any of Coroner Armitage’s 32 recommendations for preventing deaths in custody in the future.

Coronial investigations matter for families and friends of the bereaved: discovering the “truth” of how a person died, memorialising their life, and hoping their death prevents similar deaths from occurring in future.

It also matters for Australian society: improving health and safety for all, healing a community amid tragedy, and giving voice to the dead.

Marc Trabsky's research for this article received funding from an Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Researcher Award (DE220100064).

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.