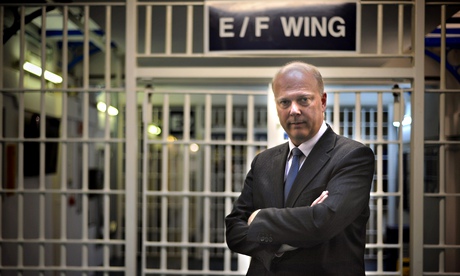

On Tuesday the justice minister made a solemn apology to the House of Commons. Chris Grayling’s mea culpa moment followed the disclosure that some telephone calls made by prisoners to their MPs had been monitored and, in 15 cases, listened to by prison staff. Clearly contrite at having to report this breach of parliamentary protocol – correspondence between MPs and their constituents is supposed to be confidential – the minister said he had “acted at a pace” to bring this to the attention of the house and was taking “immediate steps to ensure our confidentiality is respected”. I wonder if Grayling will apologise to the prisoners concerned in this breach of confidentiality rules? I doubt it.

Indeed, the news that Grayling knows how to say sorry will surprise many. He presides over a prison service in meltdown. One damning inspection report follows another. Only today, another report by the chief inspector of prisons reveals the scale of the problems besetting many jails.

It shows a 60% rise in violence in Elmley prison, Kent, including 11 mini riots in as many months. Elmley holds 1,252 men crammed into cells designed to hold 985. There have been five suicides in the past two years. About 15% of the population, or almost 200 men, were unemployed and routinely spent 23 hours a day locked in their cells. This from a government that promised to make prisoners work for their keep.

This latest report follows a series of equally damning inspections of prisons and young offender institutions in England and Wales. Violence, bullying, self-harm and suicides are soaring; many young prisoners in particular lie idle behind their locked doors during the working day; there are reports of many elderly prisoners being unable to take a bath or shower for weeks or months on end – the litany of failures goes on and on. And yet Grayling repeatedly takes to the air waves to tell the world that all is well. Until something happens that affects the privilege bestowed on his parliamentary colleagues.

While he is in the mood to apologise, will the minister say sorry to the prisoners who repeatedly have confidential mail from their lawyers opened and read before staff hand it over to them? Staff at the estimable Prisoners’ Advice Service tell me this is one of the most common complaints received from prisoners, despite lawyers clearly writing “rule 39” on the envelope.

And while Grayling’s pace is quickening, perhaps he should do what so many peers from all sides of the upper house urged him to do in a recent debate and end the torment of the thousands of prisoners detained many years after the terms the courts decreed. This problem was not of his making: the prisoners concerned were given an indeterminate sentence of “imprisonment for public protection” (IPP), brought in by David Blunkett when he was home secretary in 2003.

IPPs were scrapped in 2012, basically because they were unworkable. Prisoners had to complete offending behaviour courses before release and the courses were simply not available in the numbers required. When they were abolished, parliament gave Grayling, the lord chancellor, the discretion to speed up the release process. He has not done so. Nor has he explained why not.

In July Lord Lloyd of Berwick tabled an amendment to the criminal justice bill asking Grayling to exercise his discretion. In the ensuing debate, peer after peer condemned Grayling’s inaction. Lloyd obtained figures on those in custody who were ordered to serve short minimum tariffs.

Here is what he said to the upper house: “Eight of these prisoners with whom I am concerned were given tariffs of less than three months. Twenty-two of them were given tariffs of less than six months; 27, tariffs of less than nine months; 64, tariffs of less than 12 months; 88, tariffs of less than 15 months; 114, tariffs of less than 18 months; and 327 of them, tariffs of less than 24 months. That makes 650 in all. The current assessment in relation to 500 of those 650 prisoners is that they present a very low or, at most, a medium risk of reoffending. The question arises as to how that can possibly have been allowed to happen. Those 650 are still in prison six, seven or even eight years after they completed those very short tariffs. How can that be justified?”

In answer to the minister’s refusal to intervene in these sentences, Lloyd said: “My lords, I regret to say that I do not find the minister’s reply satisfactory in any way, no more than it was on the previous occasion. I do not intend to deal with any of his arguments, save just to mention one. He criticised the amendment on the grounds that we would be bypassing the discretion of the lord chancellors, but that is the whole point of the amendment. The lord chancellor has declined to exercise that discretion, so it is up to us now to exercise it in place of him. That is the purpose of this amendment.”

Lord Ramsbotham, former chief inspector of prisons, told peers that the IPP issue “amounts to nothing less than a stain on our national reputation for observing the rule of law”.

Will Grayling be saying sorry to the 3,600 prisoners trapped in this cruel bureaucratic mess? They are currently being released at the rate of about 400 a year. Which means it will be nine years before those 3,600 will be out of prison. Is Grayling quickening his pace and using his powers to hasten their release?

Don’t bet on it. Righting wrongs done to prisoners clearly comes a long way behind soothing the tender feelings of his parliamentary colleagues.