Auckland Transport’s environment programme director gave her own organisation a fair score on its environmental work over the last year, but said it was just the beginning of a journey. Matthew Scott reports

A three-out-of-five for environmental progress in the first year of the 10-year plan, but still a long way to go.

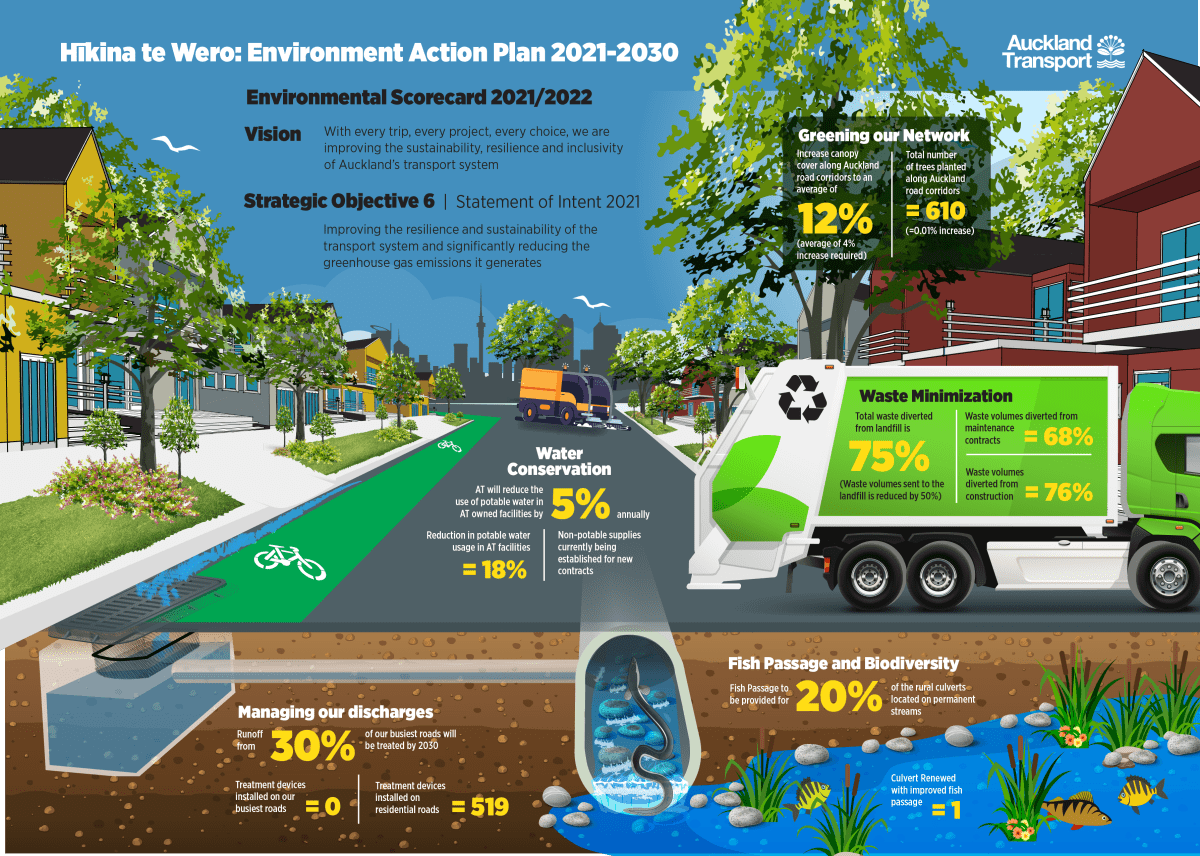

That’s the assessment of Auckland Transport environment programme director Dr Cathy Bebelman on the council-controlled organisation’s impact on the environment, one year on from its enactment of the Hīkina te Wero environmental action plan.

The plan was developed in response to recent legislative and policy changes such as the national policy statement on freshwater management and brings together disparate ends of Auckland’s transport system and how it impacts the environment.

READ MORE:

*For want of a bus driver: tough times for Auckland Transport

*Mayoral campaign: Everyone hates Auckland Transport

As the transport stewards of a busy region and the country’s closest thing to a metropolis, AT maintains and operates nearly 8000 kilometres of roads, 348 kilometres of cycleway, 7431 kilometres of footpath, 110,000 streetlights, 848 bridges, 41 railway stations, 21 ferry facilities and 16 bus stations.

To cover the impact of such a breadth of activity, Bebelman spoke about five different ways the organisation is working to reduce the impact of the transport system on the natural environment.

She said said while there had been great progress on some of the targets, there was big room for improvement on others. Her rating for AT in the first year is three out of five

“There were things we did really well and there are things we need to improve on. But it's a journey, you're not going to hit all of your 10-year targets in that first year.”

Newsroom asked Bebelman to take us through each of these five areas to point out some triumphs and explain how the transport organisation is planning to reduce the load on the environment.

Saving water

First up, the mission to conserve water. Despite the relatively high rainfall Auckland experiences, periods of drought are growing in frequency, rendering treated drinking water worth its weight in gold.

On AT construction sites, however, that drinking water is often used to keep exposed soil from becoming sources of dust.

Tankers fill up from a Watercare standpipe before spraying the exposed ground down.

Bebelman said AT is pushing construction and maintenance projects worth over $5 million to put in rainwater tanks they can use for this purpose instead.

“We've gone to all of our major contractors and we've asked them to put in large rainwater tanks at their depots, so they're collecting roof run-off to fill up their tankers,” she said.

“It's not 100 percent swap out and there will be times when those rainwater tanks are running low by the end of summer and we'll have to supplement it. But where we can, we want to encourage our contractors to be a little more environmentally aware.”

One year out from the new target being set, she said most major contractors now have rainwater tanks installed at their depots.

AT has also set a target of a five percent decrease in usage of drinkable water at bus, train and ferry stations.

Over the last year, they managed to save 18 percent, although this is in part due to pandemic restrictions.

Some facilities have gone further than others when it comes to saving water, with Manukau bus station using roof run-off to flush their toilets and depots at Wiri having water recycling drains to recapture and filter the water used to wash the trains.

Roadside ngahere

Just less than 10 percent of all of the tree cover in each local board area in Auckland comes from roadside trees – the trees sprouting from berms, providing tunnels of shade for pedestrians.

But while beautifying otherwise bare roadside corridors and providing shade are one purpose, they also play a vital role in reducing the load on the stormwater drainage system.

Trees capture rainwater through both the canopy and the root system, diverting it from the road surface and providing a passage between the sky and groundwater that doesn’t contribute to flooding risk.

It’s a responsibility weighing more and more heavily on the branches of roadside trees, as intensification and new development “seal up” otherwise permeable ground soil.

“When we urbanise our land by putting in a new subdivision or a new shopping centre for example, what we are doing is we are taking that natural ground and we are sealing it,” Bebelman said. “Roads, roofs, footpaths, parking lots. When it rains, that run off has got nowhere to go and can't soak into the ground like it used to.”

That means more stormwater discharged through pipe networks and a greater chance that they are overcome.

Bebelman said performance in this area has been “pretty poor on average”.

Trees in the road corridor contribute to eight or nine percent of Auckland’s canopy cover. AT want to bump this up to around 12 percent, especially in areas that are relatively treeless like South Auckland.

“We particularly need an increase in trees there. It would provide resilience for the communities there with shade in summer and less stormwater, reducing the run-off and potential for flooding, but more importantly trees provide shade.”

Bebelman said shade was particularly important as climate change offers the prophecy of hotter summers and more pain for bare feet on concrete.

“When I was a kid I could walk on the footpath in the middle of summer in bare feet,” she said. “You can't do that anymore, you can't walk your dog in the middle of the day in summer because the little pads on their paws get burnt. We need to bring that back.”

AT planted 610 new street trees this year, as well as trialling living shelters on two bus stops.

Why did the fish cross the road?

One area of the environmental impact of our road system that may not occur to many is the potential of roads to block the migration of native species of fish.

AT has 18,000 rural culverts to allow water to flow underneath roads and driveways, 1500 of which are on permanent streams. Bebelman said fish like whitebait use these to head upstream to quiet freshwater environments where they breed.

But just because they can get upstream, doesn’t mean they can get back. Erosion of culverts means sometimes pipes end up a half a metre or so above the water, creating a one-way voyage for the fish.

“If those fish can't get upstream to breed we lose that breeding cycle, and we lose the whitebait, we lose the food source for those native bird species that exist upstream,” Bebelman said.

AT’s target is to make sure a fifth of all rural drainpipes allow for fish passage, focusing on important routes such as a repaired culvert up in Rodney where native fish comprise an important part of the diet of the endangered fairy tern.

This can either come in the form of a wholesale replacement of a culvert, or the more economical installation of a fish ladder or fish rope.

But what does a fish want with a ladder or rope?

Bebelman said ramps with rungs on them can help fish get the traction they need to climb back into the culvert, while eels can climb up ropes.

“Some of our native species are pretty clever,” she said.

But how does she rate AT’s year when it comes to fish passage?

“It’s variable,” she said. “We're going through a bit of a discovery phase at the moment to just confirm how many of our culverts are actually a problem. What we've discovered so far is it's not a lot, and that there are some important ones that we are focusing on changing.”

Road runoff

The wear and tear of cars on Auckland’s roads means the constant and gradual accumulation of contaminants from degrading tyres and brake pads. Litter, heavy metals and micro-plastics end up as dust and sediment that is then washed away into the drainage network and out into streams and harbours.

AT’s answer is a series of filters to treat water between the streets and the stormwater system, with a target of 30 percent of the city’s busiest roads being treated by 2030.

She said it’s become more of a requirement to put them in on new developments, meaning newer quieter residential streets are more likely to be filtered.

There’s been less of a requirement to retrofit them into busy existing urban roads.

“That’s where we are focusing our work at the moment to say hey these busier roads with lots of vehicles are likely to have a higher sediment load coming off them,” she said.

While AT hasn’t installed any new treatment devices on busier roads in the last year due to Covid-related delays, 519 filters were installed on smaller residential streets.

Minimising waste

AT’s target is to divert 75 percent of its waste from construction, maintenance and network operation away from landfill.

This was perhaps the most successful area on the scorecard, with maintenance contracts diverting 68 percent of their waste and construction contracts diverting 76 percent of their waste over the last year.

There are flow-on effects to stopping waste en-route to landfill, as less money is spent on buying new materials, fewer vehicles are needed to truck material to landfill, and ultimately reducing carbon emissions.

AT’s final grade

Bebelman said she would give the organisation a three out of five for its performance in this first year of the plan.

“The scorecard represents the progress we've made over the first year,” she said. “What we're presenting is the start of our journey and how we are starting to move.”

She said hitting the eventual targets of climate action require the participation of all transport network users.

"It takes everybody,” she said. “AT just owns and operates the road and transport network. We are not the general public that's dropping the litter, we need everybody to play their part.”

That includes stopping litter before it can hit the street and preventing its eventual passage to the harbour, or electing to walk or cycle over driving to prevent that buildup of car tyre residue on the roads.

“Ultimately it’s about practical solutions to reuse materials wherever possible, not wasting drinking water for construction, and to ensure our city will stand up to the pressures of climate change,” Bebelman said.