The digital revolution has swept through the economy, changing forever the way we work and live. However, its pace has been so fast that we suddenly find ourselves in a technology-based world which too few of us fully understand. We’re increasingly savvy consumers of technology, but does it matter that most of us don’t know how everyday technology actually works?

Are we missing out on growth?

From an economic standpoint, this seems to be a growing worry. Employers complain of being unable to find the right staff, with 42% of employers saying they’re struggling to fill tech roles. It is estimated that employers require an extra 134,000 staff with digital and tech skills per year. So how and where are these extra employees to be found?

Fail to act fast enough, and future competitiveness and potential economic growth in the UK could be compromised. More of our GDP is generated from the internet than any other country. “A fully digital nation could be worth an additional £63bn to UK GDP,” says Karen Price, CEO of employer’s group The Tech Partnership. “Investment in digital technology has been shown to increase productivity by three to eight times more than other capital investment, and the vast majority of innovation – a key driver of productivity – is due to digital technology.”

BT believes a new plan of action is required to create a more tech literate UK, but what should it look like, where is more attention needed, and where should we start?

How can we get it right for the next generation?

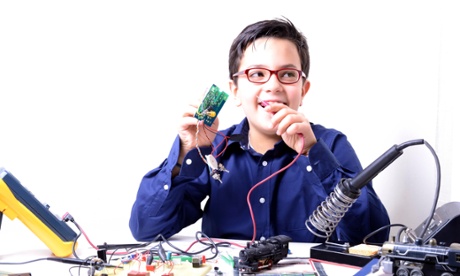

To prepare the next generation, a new computing curriculum was introduced last year – a world first for primary schools – but will it be enough to close the growing skills gap? Gavin Patterson, CEO of BT Group, says the move was a “positive first step”, but more is needed. While computing was added to the primary school curriculum last September, a survey of teachers suggested that 60% felt they were unprepared to deliver it. “We know from our own research into what kids, teachers and parents really think about tech in their lives, that many teachers still lack confidence in delivering the computing syllabus, while many kids and parents struggle to see its relevance to the real world,” says Patterson.

So what support do teachers need to help bring the value of learning tech to life for kids and parents?

What’s the best way to inspire kids so they see the creative applications of digital and tech skills?

And when the majority of teachers haven’t been involved in industry, what role could businesses play to bring the real world relevance of tech literacy into the classroom?

How can we help parents to see the point?

Parents are clearly among the most influential voices, but Justine Roberts, founder of parents’ website Mumsnet, explains the problem when it comes to engaging them. “Parents are finding it increasingly difficult to keep up with new developments in a digital age. More often than not our children are worryingly ahead of the curve,” she says. But if this is the case then how can we get parents up to speed and build their confidence? What do they need to know?

According to research for BT, another common challenge cited by parents is they simply don’t get why their kids now have to learn about computing at school. There’s a narrow view that classroom computing is “all about coding” and besides, coders and jobs in coding often evoke negative images in the minds of most parents (lonely, niche, anti–social, male dominated careers). Others admit that by contrast with other subjects, they don’t even think to ask kids about what they’ve learned in computing. So how do we help parents to see that classroom computing has wider relevance – that it’s more than just learning about computers, and will be important for their future? And is there a need to change the male-heavy, coding-dominated image of UK tech in the minds of kids – if so how, and in what way?

Patterson believes this is especially important, since it’s not just the tech sector that needs better digital skills. “Not only will there be more demand for specialist tech skills, jobs in all sectors will require some level of tech literacy,” he says.

How can we crack the girl puzzle?

As well as needing the right skills, the UK economy faces another tech-related gap - a lack of women at all levels. A survey by The Guardian found that nearly three quarters of women in the tech industry consider it to be “sexist”. Other studies show that women are also severely under-represented and so far there has been little sign of this improving. For Price, inspiring girls in schools about technology is key and she wants to see more employers going into schools. Price says one way they can do this is to get involved in programmes such as TechFuture Girls, an after-school club for girls aged 10-14 designed to keep them engaged with technology which is “transforming attitudes”.

Is tech literacy a civil society issue?

But tech literacy isn’t necessarily just about jobs, skills and the economy. According to the new civil society campaign iRights, access to tech and digital skills should be considered a modern “right”. “To be a 21st century citizen means being digitally literate… children and young people [must] learn how to be digital makers as well as intelligent consumers, to critically understand the structures and syntax of the digital world, and to be confident in managing new social norms. To be a 21st century citizen, children and young people need digital capital”, iRights argues.

If this is true, what implications does it have for what young people are taught? What gaps in their education need to be closed? And should it fall to teachers or does business have a role to play?

We’d like to hear what you think on this subject. Tweet using hashtag #techliteracy and BT will put your questions and comments to an event of 90 leading UK experts during a discussion being held on 9 September, 2015.

Content on this page was produced to a brief agreed with BT, sponsor of the technology and innovation hub