Back in March, Florida State held its pro day on campus in Tallahassee. The main attractions for most talent evaluators were cornerback Azareye’h Thomas, who would be drafted in the third round by the Jets, and defensive tackle Joshua Farmer, a future Patriots fourth-rounder. But among the 18 players who worked out that day, the one who may end up having the biggest impact on the 2025 NFL season is kicker Ryan Fitzgerald—and not because, as coverage of the event noted, he nailed a 68-yard field goal in front of scouts.

After most attendees had left, Fitzgerald had an hour-long semiprivate meeting with a few curious NFL team reps. Dan Orner, a private kicking coach who had been working with Fitzgerald for a few years, says scouts from the Browns and Giants asked his pupil to go through an additional battery of workouts that showcased what Orner calls the kicker’s “bag of tricks.” For a year, Fitzgerald and Orner had been practicing ways to “knuckleball” a kickoff, with just this moment in mind.

The importance of that conversation would become clear less than two weeks later, when NFL owners voted at their annual meeting on April 1 to tweak the touchback rule: Offenses would now get the ball at the 35-yard-line rather than the 30. (You may have missed the change at the time since everyone was screaming about the legality of the Eagles’ Tush Push, which was hotly debated at the meetings.) Over the last five seasons, drives that began at the 30-yard line scored a touchdown or field goal at a rate of 37.4%. Drives that began at the 35-yard line scored at 44.8%. A touchback that put the ball at the 32 or 33 might still have made kicking the ball out of the end zone a smart play. But inside the NFL analytics community, the consensus is that the five-yard difference equated to a statistically significant addition of expected points.

Suddenly teams were far more wary of handing an opponent a touchback, and some of them became extremely interested in alternative kickoffs that would hit the ground in the landing zone and allow the coverage team to leave its stationary position. A ball that bounced unpredictably and was difficult to field would be a significant bonus.

With all of this in mind, those curious souls in Tallahassee watched as Fitzgerald showed how he can keep his leg swing consistent but, based on the tilt of the ball, the placement of the tee or the strike point, make the ball behave in strange ways. For one of his knucklekicks Fitzgerald, a right-footed kicker, tees the ball up like a left-footed kicker would, making it look a bit curved like an end parenthesis. The higher the strike point toward the ankle and the higher the strike point on the football, the more the ball dances in the air.

The scouts asked if Fitzgerald could disguise his intentions, making a knucklekick windup and a traditional windup look identical. He could. They asked if he could keep the knuckleball action consistent from the right to the left. He could.

“They basically said, ‘Please don’t show this to anyone else,’” Orner says. “And that’s when I said to Ryan, ‘Congratulations, you just made the NFL.’”

Fitzgerald ended up signing with the Panthers as an undrafted free agent. The obscurity of his unique kicks and those of another of Orner’s clients, the Rams’ Joshua Karty, didn’t last long. Through the first 10 weeks of the season, Carolina (26.8-yard line) and Los Angeles (28.2-yard line) ranked second and third in average opponent starting field position after kickoffs. The sudden weaponization of the kickoff has been just one aspect of a special teams revolution this season. Through Week 10, there were 23 blocked field goals and punts, with three of them directly deciding the outcome of a game in the final seconds. More 50-plus-yard field goals were being attempted per game than at any time in NFL history, other than last season. More field goals of any distance were being made than ever. The number of kick returns per game more than doubled from 2024.

Seemingly overnight, an aspect of football once seen as an excellent opportunity for spectator bathroom breaks was sparking some hard questions. Should practice time be reallocated for special teams? How should kickers, punters and returners be valued? What really makes a good special teams coordinator? Should more starters be playing special teams? And, yes, should parents be buying their grade-school kickers tile brush power tool attachments so they can doctor their kicking balls like the professionals? (Too late, it’s already happening.)

John “Bones” Fassel of the Titans, one of the league’s most experienced special teams coordinators, says that, in the best possible way, his reaction has been: “What is going on?!” He and many other coaches say this season has sparked new levels of intellectual curiosity and creativity around the kicking game.

“Special teams are the wild, wild west,” Fassel says. “You just don’t know what is going to happen.

In the spring of 2024, three men walked onto a vacant practice field in Houston, determined to figure out what the future might look like.

Frank Ross, the Texans’ special teams coordinator, is one of the league’s most successful and the winner of the final two Rick Gosselin Special Teams Rankings (the legendary Dallas sportswriter, who retired the list after the 2023 season, created a 22-point grading rubric for kicking-game units that became an industry standard for rating special teams). Ross, assistant special teams coordinator Will Burnham and hybrid assistant Sean Baker stood roughly seven yards apart from one another and started experimenting with the bones of what a new dynamic kickoff might look like if it ever came to the NFL. There was nothing to work off of save for tape from the XFL, the alternative league which featured a similar kickoff.

They started working through their own theories, playing the roles of kickoff blockers or coverage men. Ross would ask Burnham if, in a certain situation, he could track him down at a certain angle. To the uninitiated, it may have looked a bit like synchronized swimming practice on dry land. Ross says it was “a bunch of 5'10" white guys,” and describes the movements on the field that day as “not explosive.”

That day Ross created what he calls his “feedback loop”: a hard file of a running dialogue with his players that is still in use. Because everything was created from scratch, everything was tailored to the abilities of the players at his disposal. Was any of this comfortable for them? Were the movements coaches were asking them to make feasible?

“It wasn’t necessarily about X’s and O’s,” Ross says. “What do you want your feet to look like? How do you envision yourself? This sounds silly, but do you want your butt in or out to the sideline?”

“Anytime there’s a change then it’s a race to who can figure it out,” Burnham says. “So I’d say the first feeling was excitement because you really are throwing out a lot of years of football.”

This moment reflected the true malleability of special teams from 2024 to the present day. There are raging debates over the use of larger players (tight ends, linebackers, fullbacks and defensive ends) on kickoff returns and how overall roster construction can favor or adversely impact kickoff unit personnel. Kickoff returns will evolve constantly over the next few years, coaches predict.

The evolution extends beyond kickoffs. Take the boom in longer field goals. Kicking experts like Orner say that, outside of the fact that teams are now allowed to prepare “K-balls” throughout the week to make them more kicker-friendly instead of only on game day, the biggest change in the kicking game is that kickers are now plucked from a much more athletic pool and have become less dependent on wedge-style kicking. This method, which uses the inside of the foot, was accurate but sacrificed power. Now, according to Orner, young kickers are more likely to also be track athletes or stars in other sports. Kicks are recorded with the precision of Tiger Woods’s backswing and examined for the smallest of adjustments. Middle schoolers have personal kicking coaches. Orner also believes that college football’s mass import of kickers and punters from Australia raised the bar for American kickers who had to compete with far more natural and experimental kickers.

In the first 10 weeks of this season, teams attempted 150 field goals of 50 yards or more. That number has been climbing in recent years; as recently as 2020 there were only 168 attempted all season. The very real possibility that someone will soon make a 70-yard field goal, the likes of which Jaguars kicker Cam Little hit in the preseason, would then seem to be the culmination of these parallel transformations. Little also set a new regular-season record with a 68-yarder at the Raiders’ indoor Allegiant Stadium in Week 9.

But Ross wonders if we’re missing something.

“I’ll ask you a question,” he says over the phone just a few days before the Texans took on the Seahawks in Week 7. “Who is a better shooter, Ray Allen or Steph Curry?”

He continues: “There’s an argument for both. I probably would say Steph, but Ray Allen was at one point the all-time leading three-point shooter, right? Well, Steph necessarily isn’t a better shooter, but he changed the game because he was more confident to shoot from different spots further away. So is [Cowboys kicker] Brandon Aubrey a better kicker than [former Patriots kicker, five-time NFL scoring leader and four-time Pro Bowler] Stephen Gostkowski? Or, is Brandon Aubrey just shooting from different spots?”

Another point of division? Kick blocks. Through Week 10 the league was on pace for 29 field goal blocks. There were 18 total last year. Some NFL coordinators blame the surge on a hangover from the preseason, where teams don’t typically rush kickers aggressively and almost never rush them live in practice. Like missed tackle numbers that tend to even out once players acclimate to the physicality, blockers will be less likely to get mauled by more skilled defensive players.

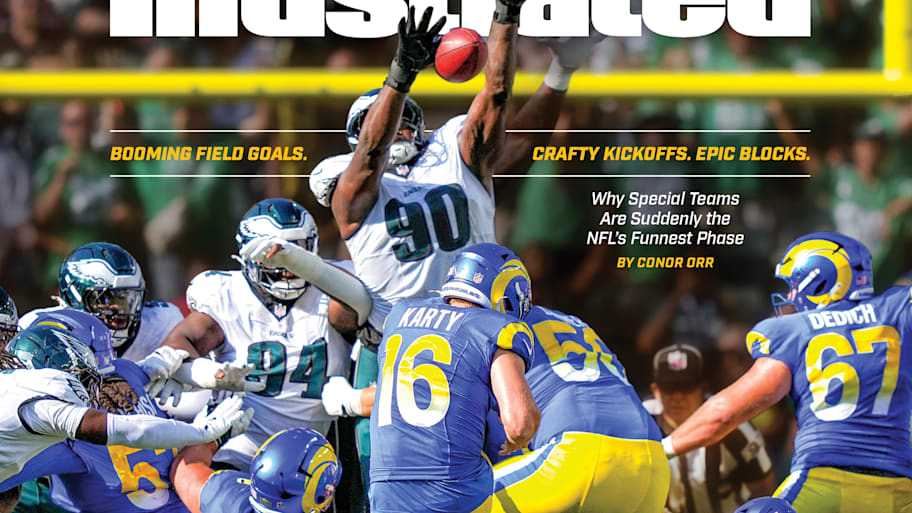

However, others concede that there is a greater focus on the science behind kick blocking, just as there is on kicking itself. Fassel and the Titans had one of the most visually satisfying extra point blocks of all time in Week 2 against the Rams, when Arden Key arrived in front of kicker Karty fully in rejection mode, arms rising above his head in the shape of a diamond and swatting the ball half a field away.

“You could hear the ricochet off his elbow and face mask and it shot like 40 yards backwards,” Fassel says. “Yeah, that was cool.”

In Week 3 the Eagles blocked Karty on two consecutive field goal attempts utilizing a rush scheme that bludgeoned one of the Rams’ protectors in the outer “C” gap and performed what coaches call a “corkscrew” action to penetrate the vacant space. The attack was so precise that the Rams tried to counter—it didn’t work—by replacing one of its blockers from one kick to the next. Clearly, Philadelphia knew the pressure point it was trying to expose.

It could be that all of this—knuckleball kicks, longer field goals, an increased number of blocks—are at least somewhat connected. Mike Westhoff, one of the NFL’s most recognizable special teams coaches, who retired after a 33-year career last year, feels that kickers attempting 70-yard field goals are unconsciously lowering the angle of the ball, a necessity to drive it longer distances, thus making it easier to block. And the inability to protect kickers may be a kind of breaking point of roster construction. Reserve offensive linemen, backup tight ends and defensive players, some of whom make up the protection units on field goals and PATs, are worse and less experienced as blockers than ever before. This was an inefficiency ripe for taking advantage of, especially since, as special teams coordinators can universally attest, none of them were given an increase in practice time during the week to solve all these issues.

Commissioner Roger Goodell, when asked about the new kickoff during the league’s international series, admitted there was an intentionality behind bringing special teams to the forefront, though fixing one problem could have “another effect.” Regardless, everyone touching the sport feels it. Longtime kick returners like Jamal Agnew of the Falcons says he feels revived, no longer relegated to eternally watching touchback kicks fly over his head (“I always want to take it out on every kick,” he says). Kickers are emboldened, with some in their circles wondering if dominating field position means bigger paydays (most kickers in the NFL make less than $4 million per season). Coaches, Ross says, have more access to “varsity” players than ever before.

Ross also says something one can imagine many special teams coaches are thinking but aren’t quite ready to say out loud.

They have long been ignored for bigger opportunities (the Ravens’ John Harbaugh is the only current NFL head coach with a majority special teams background, and even he had to spend a year as a defensive position coach before getting hired by Baltimore), and no special teams coordinator has ever won the assistant coach of the year award. But now special teams specialists are seeing a public legitimization of private mastery.

“Special teams is not just a slack hire anymore,” Ross says. “It’s a factor. It matters and I think it’s going to continue to shape the game.”

*through Week 10

As Orner, the private kicking coach, was getting off the phone, the car door shut and he began walking toward the practice field for a lesson with a youth client currently in ninth grade—one of hundreds of clients in high school or college.

In his spare time Orner has been scouring Instagram pages of amateur kickers—some without any traceable sports background—making trick-shot kicking videos and high-wire soccer free kicks. He says he learns as much from younger kids, and these videos, as he does from professionals. This is going to be the future—an opinion that Orner shares with many special teams coaches, who believe that knucklekicks are just the beginning.

“I watch that stuff and people would think I’m crazy,” he says. “But I’m not crazy when two of my guys [Fitzgerald and Karty] are leading the league in field position percentage.”

Orner says that Fitzgerald, for instance, has yet to debut in an NFL game a version of his knuckleball kick that does not require any steps to lead in. He imagines that by Week 13 or 14, Fitzgerald will be able to debut “the real cool ones.” When pressed for details, he says Fitzgerald and Karty can kick balls that have a helicopter-style spin; balls that, from their right foot, can mimic the banana-like wobble of a left-footed punt; and, with less consistency, something that he refers to as the “Texas Tornado.”

“It spins like a tornado [when it hits the ground] and it will run back 15 yards,” he says. “Just like Rory McIlroy’s pitching wedge. We’ve been working on this for about three or four years and we finally got some distance to it. So we’ll see.”

With this in mind, a recent Giants practice took on an entirely different vibe. Silence across a chilly, sun-splashed field in East Rutherford, N.J., was broken by the loud thwump of a football barreling end over end through a JUGS machine toward return man Gunner Olszewski, who was simulating his task for the weekend ahead. As the wind picked up and the angle of the machine was altered, some of the balls drifted left or right. One of them died at his feet and bounced off his shin.

The Giants had two players—punter Jamie Gillan, a Scottish-born rugby player, and kicker Jude McAtamney, an Irish-born former Gaelic football player—who can hit knuckleball kickoffs in practice. A third, long snapper Casey Kreiter, is spotted sometimes attempting knuckleball kickoffs and his special teams coordinator, Michael Ghobrial, will look over and say, “What are you doing, dude?” (McAtamney was released a few weeks ago.)

Ghobrial, who coaches one of the best kickoff coverage units in the NFL, says that he could probably hit a knuckleball too, just not on purpose or with any idea of where it might land.

His joke broke the seriousness of what was otherwise a display of how deeply he cares about his life’s vocation. He wasn’t buying the idea that his day-to-day experience amid this special teams coup was necessarily different for him because “the level of importance of special teams has always been held with the utmost regard.”

He adds: “It’s why I do what I do.” Still, he admits that now everyone is watching the opening kickoff. Everyone is watching the return. Everyone is watching every field goal and punt and extra point. It matters in a very specific sense as it pertains to expected points and field position and the little moments that now define wins and losses like never before.

But it also matters because something—a way of life—out there on that sunny practice field, and thousands everywhere just like it, was about to die.

“To have it back,” he says, just minutes before donning a royal blue jacket and lining up his punt unit, “is exceptional.”

More NFL From Sports Illustrated

This article was originally published on www.si.com as How a Special Teams Revolution Suddenly Reshaped the NFL.