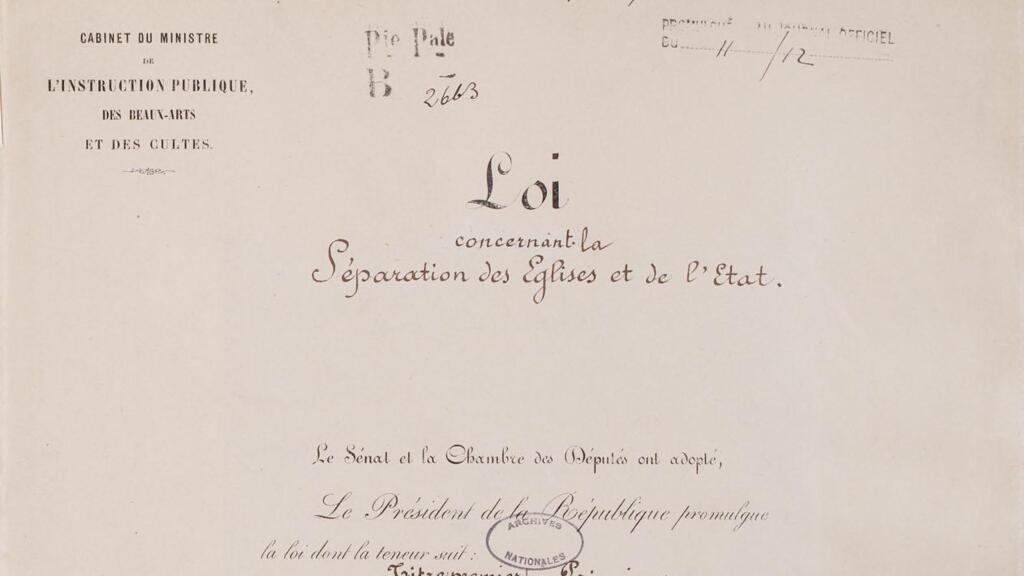

On 9 December 1905, France abolished Catholicism as the state religion after MPs voted to separate church and state, a move that redefined the relationship between the republic and religious worship and founded the principle of secularism seen in modern France.

Under the monarchy, the Catholic Church held major privileges and played a central role in society. The French Revolution of 1789 upended this order. Revolutionaries nationalised church property and required priests to swear allegiance to the new republic. Those who refused were persecuted.

Napoleon later tried to ease tensions by signing the Concordat of 1801 with Pope Pius VII. The state recognised Catholicism as the faith of most French people, but also recognised Reformed Protestant, Lutheran and Jewish communities. It appointed bishops and paid the clergy.

This system lasted throughout the 1800s but kept tensions high – particularly under the Third Republic, when republicans viewed the church as blocking modern reforms and supporting conservative forces.

French court orders town to remove statue of Virgin Mary

The scandal that paved the path

In 1894, Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish artillery officer from Alsace, was wrongly convicted of treason and sent to a penal colony in French Guiana. This miscarriage of justice split the country. On one side stood Dreyfusards, who defended his innocence in the name of justice and truth. On the other, the anti-Dreyfusards refused to question military authority.

The Catholic Church strongly backed nationalist, anti-Dreyfusard groups and relayed anti-Semitic arguments in the press. This shocked republicans, who questioned how the church could oppose the values of justice, equality and truth.

Many concluded that as long as it held influence over institutions and political life, it posed a danger to democracy.

Aristide Briand gained prominence during this period. A lawyer, journalist and moderate socialist, he was elected as an MP in 1902 after a campaign dominated by religious questions.

Prime minister Émile Combes initially avoided any reform, despite pressure from the republican majority. But rising tensions with the Vatican changed his stance. He created a commission on separation, with Briand as rapporteur.

From March 1905, Briand orchestrated one of the longest and most passionate debates in French parliamentary history. Two visions of France faced each other: one monarchist and Catholic, the other republican and secular.

Briand chose the middle way and pushed for compromise, rather than confrontation.

"We are not making a law against religious worship, we are making a law of freedom," he said. His aim was to guarantee freedom of conscience and equality before the state without persecuting religions.

The word laïcité, or secularism, does not appear in the 1905 text, which uses only the term separation.

However, the first two articles set out the founding principles of today's laïcité: the state must stay neutral towards all religions, favour none, finance none and prohibit religious expression in public institutions. The term secularism entered the constitution in 1946.

'Growing number' of French schoolgirls flouting secularism rules

Violence over inventories

Many Catholics saw the 1905 law as a tragedy and refused to accept it. Church property had to be transferred to new religious associations, which required a full inventory of buildings and objects. State agents entered churches and presbyteries to draw up reports, and many faithful viewed the inventories as a desecration of sacred places.

Prefects were told to enforce the law while avoiding clashes, but violence still broke out. Bloody incidents occurred in Haute-Loire and in the Nord region near the Belgian border.

Géry Ghysel, a 35-year-old butcher and father of three, died in the village church of Boeschèpe, in the Nord department, during an inventory that turned violent.

On 11 February, 1906, less than two months after the law’s adoption, Pope Pius X issued a fierce response. In his encyclical Vehementer Nos, he condemned the separation of church and state.

"That the state must be separated from the church is an absolutely false thesis, a most pernicious error," he said, adding that it was "gravely insulting to God, for the creator of man is also the founder of human societies and he preserves them in existence as he sustains us".

Diplomatic relations remained broken until 1921.

Top French court upholds ban on Muslim abaya robes in schools

Exceptions in Alsace-Moselle

The 1905 law was not applied in Alsace-Moselle, which was then under German rule, having been annexed after France’s defeat in the Franco-Prussian War in 1871.

When the region was returned to France in 1918, the 1905 law still did not apply there, and still today the Bas-Rhin, Haut-Rhin and Moselle departments have retained local rules inherited from the 1801 Concordat, which had defined the relationship between the French State and the Catholic Church.

Priests, pastors and rabbis are paid by the state through the interior ministry, and religious education remains compulsory in public schools in the region.

The 1905 law devotes very few articles to public education, since secularisation of schools had already begun with the Jules Ferry laws of 1882, which removed religious teaching and replaced it with moral instruction.

By 1886, teaching posts were held only by lay staff. The Ligue de l’Enseignement, created in 1866, became a major supporter of a free, secular and compulsory school system and built a wide network of cultural and educational activities as an alternative to Catholic youth groups.

Modern battles

With social change, debate over religion in public spaces – especially in schools – has remained intense.

In 1989, several Muslim pupils were suspended from a school in Creil, north of Paris, for refusing to remove their headscarves. More such cases followed.

On 17 December, 2003, then president Jacques Chirac called for a stronger defence of secularism amid rising demands from religious and community groups.

A law adopted in March 2004 and applied from the following school year banned conspicuous religious signs in public schools, including headscarves, kippas and large crosses.

French court issues severe sentences to those linked to beheading of teacher Samuel Paty

After the January 2015 terrorist attacks at the office of Charlie Hebdo and the Hyper Cacher supermarket, then education minister Najat Vallaud-Belkacem reaffirmed the importance of secularism. She established national Secularism Day on 9 December and introduced new moral and civic education guidelines.

The murder of history and geography teacher Samuel Paty on 16 October, 2020, after he used Charlie Hebdo satirical cartoons in a class on laïcité and press freedom, marked a turning point. Schools had become targets for extremists because of the secular values they defend.

In August 2021, the 1905 law was amended with the tightening of controls on organisations and places of worship, particularly with regards to foreign funding – presented as a way to combat radical Islamism and other forms of separatism.

This article was adapted from the original version in French by Patricia Blettery.