In 2023, the British filmmaker Campbell X put out an invitation on social media to “please share with me your most controversial take on LGBTQI films”. Among those who responded was Francis Lee, the director of God’s Own Country and Ammonite. “Make your gay characters complex,” Lee said. “Problematic. Nasty f***ers who do bad things. Unapologetic. Evil. Manipulative. Unlikable. Three-dimensional. Villainous. Not just the ‘cute’ teens holding hands.”

It’s an admirable goal. And yet that manner of portrayal invariably encounters opposition from funding bodies, festival selection panels and distributors before it can even reach critics and audiences. One of the most egregious examples of a radically queer film being stymied on its way to the marketplace is Sam H Freeman and Ng Choon Ping’s 2023 thriller Femme. Nathan Stewart-Jarrett plays Jules, a statuesque drag queen who is the victim of a homophobic attack. Months later, he spots his closeted assailant, Preston (George MacKay), in a gay sauna. Preston doesn’t recognise him out of drag, which gives Jules the chance to contrive a sexual relationship with him as revenge.

Raising the budget was a challenge even off the back of a Bafta-nominated short of the same name. A leading UK body turned the film down at the funding stage. One company pledged a chunk of the movie’s budget, only to withdraw it six weeks before shooting was due to begin. Privately, its executives expressed doubts about the commercial viability of Black queer content, as though the casting of Stewart-Jarrett as Jules might limit the film’s appeal.

It was always Ng’s preference that one of the leads should be played by a person of colour. “Our desires are shaped by what we see,” he says. “So I was keen to tell a story that was outside the usual two white guys. But it wasn’t a deal-breaker.” None of the characters were written as a specific race; it just so happened that Stewart-Jarrett was the best actor who auditioned to play Jules. “No one we saw held a candle to him,” says Freeman.

Femme had its world premiere at the Berlin Film Festival in February 2023. “People gasped in the right places,” says Ng. “There are many ways Jules’s story could have gone: it might have addressed healing and reconciliation, or it could’ve been an exploitation traumapalooza. But we wanted to make a thriller, which is not traditionally a space for queerness, and that’s how it went across in the room that night.” The film received a standing ovation. “It was emotional,” says Stewart-Jarrett. “We all believed in the film, and here we were in this moment of joy.”

What happened next was unfortunate. “It’s 11pm, we’re all up on stage – Ping, Nathan, George and myself – and the moderator asks a few things,” Freeman remembers. “It’s going well. Then they go to the audience for questions, and this guy stands up. He has something written down, and he starts reading from it: ‘In a world where violence against trans people is at an all-time high, why would you choose to make a film where…’” He sighs. “I can’t remember the rest. Ping and I looked at each other and panicked.”

There was a good amount of interest from relatively big names. But generally, you’d hear that younger members of the team weren’t happy. There’s this weird point where [well-meaning liberals and the right wing] kind of meet, even though they might hate each other

Stewart-Jarrett stepped in with a rejoinder along the lines of: when it stops happening on the streets, we won’t need to show it on-screen. “Nathan handled it so well,” says Freeman. Who was the disgruntled speaker? “I heard he was a filmmaker. He had this campy, queer sci-fi film on the festival circuit around the same time as us. I’m trying to remember his name. Rabbit something. Harvey Rabbit maybe?”

***

“Before we proceed, I would like it to go on the record that the storytelling and everything about the filmmaking [in Femme] was great. I do not want to insult these folks.” Harvey Rabbit is speaking from his apartment in Berlin. He has black-framed glasses and thick mutton chops and is wearing bright blue dungarees over a striped long-sleeved T-shirt. He is the director of Captain Faggotron Saves the Universe, a comic fantasy about a swishy superhero, his intergalactic alien non-binary ex-lover and a horny gay Christ.

After the Berlin screening of Femme, Rabbit was the first to take the mic. “I knew this was their world premiere. I didn’t want to ruin their moment but I was just so mad.” His displeasure began before the movie did. “The directors came on stage to introduce the film. They’ve got this huge audience and they’ve both chosen to represent themselves in a masculine fashion in terms of clothing. And that’s fine. I know there’s a lot of discrimination against cis gay men, and that they face violence and threats, too. I get that. Especially as I appear to be a cis gay man, and I can tell when some dude is not OK with who I am. Even if they have no idea I’m trans, I somehow threaten their masculinity. But to go to a movie called Femme and then to see these cis men on stage who don’t have any gender-f*** going on, no makeup, no display of queerness – that’s a little bit of an alarm bell for me.”

When the microphone reached Rabbit, he let rip. “I was attempting to make my point and be diplomatic, but I wanted an answer to my question.” Which was? “Just: ‘Why?’ Why show that people who challenge the gender binary are going to face violence, even if you’re saying it shouldn’t happen? Why show it at all? But especially in the time we’re in right now, with so much violence against femmes and trans women of colour … I just want to see more femmes and trans characters having a good time on camera. With the protagonist here, I don’t even know if getting revenge made him feel better.”

It’s been more than a year since he saw the film, so I remind him how the story plays out: Jules fosters with Preston a sexual and emotional closeness over several months, leaving his assailant vulnerable, invested and (as the final scene shows) capable of tenderness. Jules’s revenge is anything but sweet. It’s ugly and complicated, and it’s intended to leave the viewer conflicted. “I do think there’s room for that kind of story,” Rabbit says. “My issue was he didn’t get to experience any joy. None. He’s just miserable. I want to see femmes win! I want to see trans people win!”

In the months that followed the premiere, Freeman and Ng received multiple knock-backs. They heard that people in the industry were wary of supporting a film that had a Black protagonist but no Black director – a judgment call which paradoxically robbed Stewart-Jarrett of any agency. “There is a lack of directors who are not white,” the actor points out. “We know that. So am I only meant to work with Black ones? If so, I’m not going to work very often.”

Concerns over the subject matter proved even more pressing, and soon a pattern began to emerge. First, there would be initial enthusiasm from prospective distributors, even the promise of a bid. Then the heat would cool after other employees on those teams voiced objections to the brief scenes of violence which bookend the film, or to the idea of queer trauma.

“There was a good amount of interest from relatively big names,” recalls Freeman. “But generally, you’d hear that younger members of the team weren’t happy.” In such situations, it becomes possible for a well-meaning liberal aversion to the dramatisation of trauma to coincide, albeit inadvertently, with a right-wing tendency to police or nullify challenging queer material. “There’s this weird point where they kind of meet, even though they might hate each other.”

One of the most significant snubs came from the BFI London Film Festival, which declined to programme Femme. I ask Harvey Rabbit whether he thinks his Berlin tirade might have harmed the film’s chances at the LFF. “That’s highly unlikely,” he says. Freeman isn’t so sure: “There were people from everywhere in the room that night. Who knows how much damage he did? He really threw a grenade at us.”

Femme did find a UK distributor, which marketed the film bafflingly as a straightforward thriller, putting it predominantly into outer-London multiplexes when it should have been playing arthouses. Indeed, one of the sticking points seemed to be that Femme doesn’t behave like a gay film; sexuality isn’t its subject. Instead, it trespasses on the heterosexual terrain of the genre movie, looking and acting like a thriller.

“It sat between two stools,” says the film’s executive producer, Harriet Harper-Jones. “The straight audience felt discomfort because it’s a gay film that is not issue-based. And there was discontent within the privileged, mainly white gay community, where the reaction has been: ‘How dare you? It’s a Black gay character suffering violence and you’re trying to make it commercial.’ If Preston was vilified, and if Jules was a good gay Black man who was attacked but then sought redemption and became this happy drag performer, everyone would have loved that. But Jules is both the victim of a violent act and a perpetrator. It’s the whole f***ing manifesto of the film: it’s about the cycle of violence.”

The movie’s profile was so low that by the time awards season rolled around, many voters simply hadn’t seen it. Femme triumphed at the British Independent Film Awards, where voting is weighted differently from other awards bodies: a film earns nominations based on how highly it scores with those who see it, rather than the number of people who vote for it. In that instance, it received 11 nominations and won three prizes, including Best Joint Lead Performance.

At the Baftas, however, it failed even to make the longlist for Outstanding British Debut. “To not make it to the longlist for Bafta … well, that felt loud,” says Freeman. Harper-Jones puts it more bluntly: “To me, that is a scandal.”

The movie was picked up by Utopia in the US, where it went down a storm. Ryan O’Connell, star and creator of the queer Netflix series Special, called it “a f***ing breath of fresh air, a movie that is challenging and complicated”. Megan Ellison, the producer who rode to the rescue of the queer animation Nimona after Disney dropped it, tweeted about Femme: “I absolutely love this film … Content warning: it’s very gay.” John Waters, Bret Easton Ellis and Bruce LaBruce are also fans. “You always hope a film will live on,” says Stewart-Jarrett. “And Femme does appear to be quietly snowballing.”

Today, Freeman confesses to being exhausted by the picture’s turbulent journey. “We’d put so much of ourselves into making something we thought was honest and nuanced and complex. And so this response from certain parts of the industry that it was in some way dirty or offensive, or that it was a story we shouldn’t be telling … that was tough. There were points, when I was caught up in it all, where I questioned whether I’d want to make something a little safer next time.”

“If we did the film again, I would make all the same choices,” says Ng. “One should never expect 100 per cent support. That’s unrealistic. But where the lack of support comes from can surprise you. There’s this idea that you can only have one type of freedom, because only that type is real and valid. We even deal with it in the film, when Jules’s flatmate tells him he shouldn’t go around carrying all this self-loathing. It’s queers policing queers.”

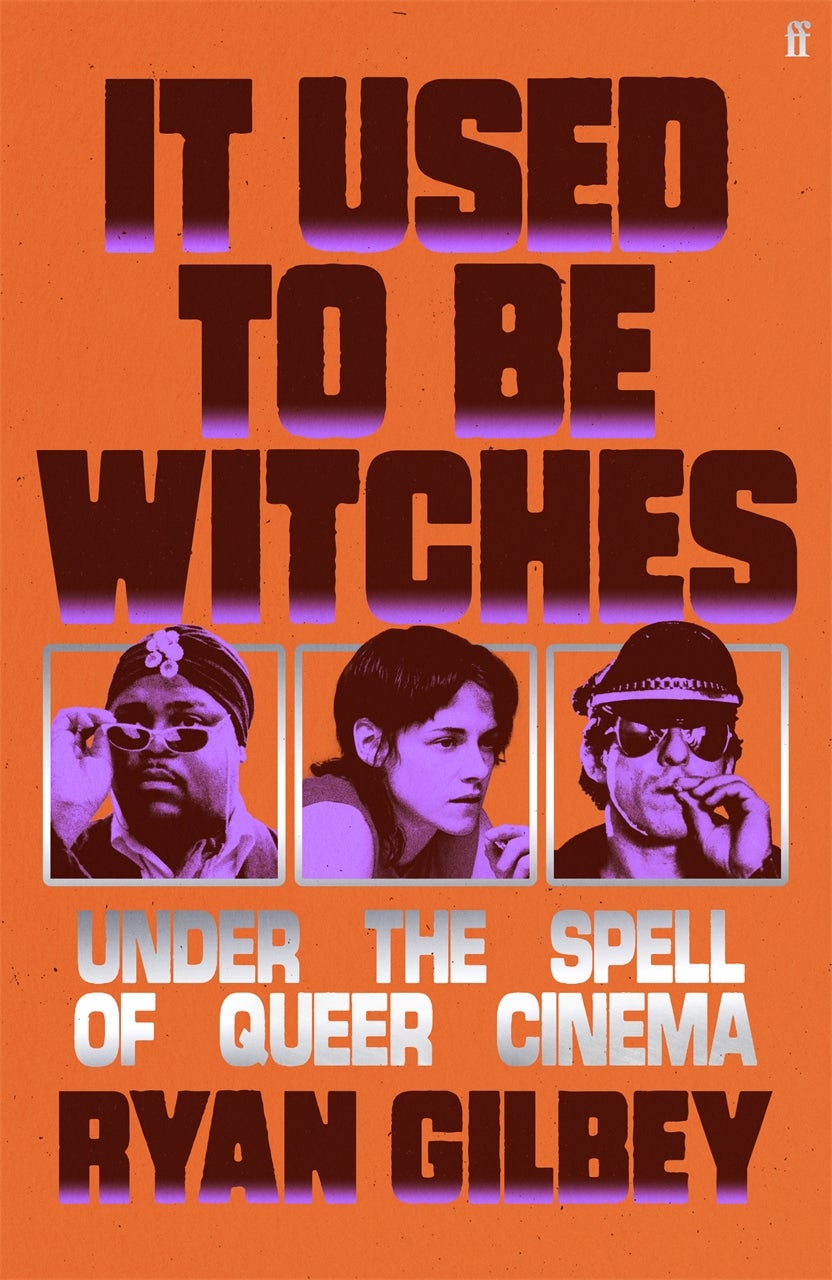

This is an edited extract from ‘It Used to Be Witches: Under the Spell of Queer Cinema’ by Ryan Gilbey, published by Faber on 5 June

Ryan Gilbey will be in conversation about the book at Foyles, Charing Cross Road, London, on 4 June, and at the Cinema Museum, London SE11, on 15 June, and will introduce a screening of ‘Femme’ at the Ultimate Picture Palace, Oxford, on 1 July