Kuntilanak, a long-haired, pale-faced woman with staring eyes, is peering from the shadows. Babi ngepet, a black-magic boar demon, snarls before a bloody attack. The pocong, a white-shrouded corpse, is coming closer and closer. These macabre characters are among the ghosts waiting for players of the video game DreadOut.

Grotesque and haunting, DreadOut has made Indonesian independent gaming studio Digital Happiness one of the Southeast Asian nation’s few game developers to find international success, reeling in US$7.5 million in sales and landing a movie adaptation from a big-time Indonesian film director.

The game was Digital Happiness’ first major project, and the studio now hopes to expand globally with a newly released sequel. After all, it has scary ghosts on its side.

“Our local ghosts are not only unknown [and therefore mysterious], but they are scarier than your Slenderman,” says Digital Happiness founder Rachmad Imron, 39, half-jokingly, referring to the faceless supernatural being born in the English-speaking realms of the internet.

DreadOut’s narrative theme is typical of horror fiction. A group of high-school students go on a trip, get lost, and wind up in a mysteriously empty old town. They find themselves in a school where the protagonist, Linda, begins running into ghosts and using her smartphone camera to fight them off.

The goal of the game, played largely in the third person, looking over Linda’s shoulder, is to capture as much information as possible about the ghosts and solve the mystery of the town’s haunted history.

“The ghost experience is a universal thing,” Rachmad says. “Everybody is bound to have some sort of scary story related to their everyday existence and environment – and many of those happen at school.”

Some of DreadOut’s supernatural beings move eerily slowly, while others attack like hungry wolves. The game’s darkness and electro-goth soundtrack help conjure up a feeling of fear and foreboding.

“In terms of exposure, it’s one of the most successful Indonesian games ever,” says Pladidus Santoso, who reviewed the game for the Indonesian gaming website JagatPlay.

Pladidus thinks the DreadOut creators are pioneers and others have followed in their footsteps. “Now there is a tendency for local developers to create horror games using Indonesian mythology as a background,” he says.

Digital Happiness, a four-person studio in Bandung, West Java, was founded in 2011 by Rachmad, who had previously created technical 3D animations for businesses around Indonesia, particularly in the construction industry.

He had spent more than 10 years in the business world and was ready to make his personal mark in the gaming field. The seed for the studio had been planted in 2004, when he created a vehicle simulator game for the Indonesian army. But “the video-game dream”, as he calls it, would have to wait.

“The Indonesian gaming ecosystem [in 2004] was not as good as it is today, so that simulator game did not sell,” Rachmad recalls. DreadOut brought the dream to life.

In 2013, two years after Digital Happiness was launched, Rachmad and co-founder Vadi Vanadi, 34, bought Unity, a cross-platform game engine developed by the Danish-American gaming software company Unity Technologies.

“From then on we were able to conceptualise DreadOut, learn more about the gaming ecosystem, and start working on an actual business model,” Rachmad says.

Like many Indonesians who came of age in the 1980s and early 1990s, Rachmad’s childhood was filled with Japanese children’s entertainment. Anime cartoons and superhero robot sentai series shared space with ninja and samurai video games in his mind. He loved learning about the traditions of other nationalities through pop culture. So he knew DreadOut had to be set in Indonesia.

The unusual location gives the game an edge of difference, and a huge pool of ghostly inspiration to draw on.

“We looked into the more than 17,000 Indonesian islands and over 300 dialects that we have here, and we knew we had a lot of ammunition to work with, in addition to the many urban legends and lore that we already knew about. I mean, just the kuntilanak ghost alone has so many differing backstories,” he says, referring to the long-haired, child-stealing ghoul.

“We looked into the social background and culture that some of those folklore spooks came from – like the legend of the kuntilanak, who came from the city of Pontianak [in Borneo],” Rachmad says. “We learned those stories and tried to infuse them into the DreadOut story.”

When they first set up the Digital Happiness studio, Rachmad, Vadi and their friends were short of funds, so they launched a campaign on the US crowdfunding website Indiegogo, where many creative dreams become reality.

Hopeful but realistic, they were astounded when their goal of US$25,000 was surpassed before the five-week deadline, with the total raised finally reaching a little over US$29,000.

Rachmad and Vadi began programming the game, while the other two members of the Digital Happiness team – technical artists Sukmadi Rafiuddin, 34, and Dwi Arif Irawan, 37 – tried to find more money and sponsorship.

By the time of its release in May, 2014, DreadOut was an assured hit. The success of the Indiegogo campaign had spawned word of mouth interest through Indonesia’s gaming community. Released exclusively for PC via the digital-distribution service Steam, the ghostly game began selling and has not stopped.

Rachmad says that by the last count in mid-2019, DreadOut had been downloaded 2.5 million times.

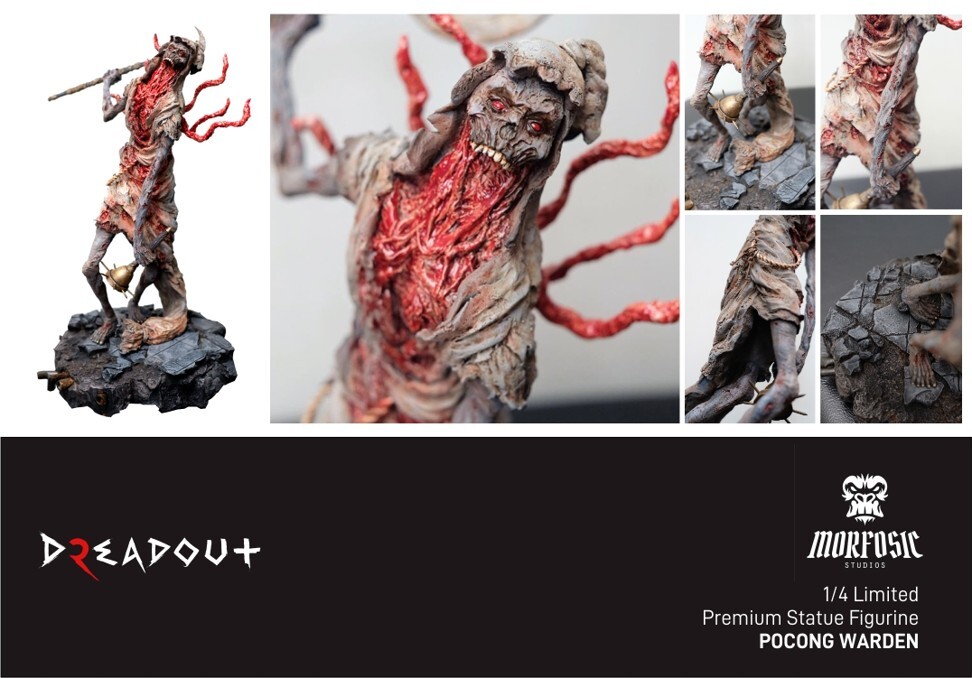

Local toy company Morfosic soon offered to make the first major DreadOut merchandise – a collectable mini statue set.

The game had another boost when PewDiePie, the popular Swedish YouTuber, posted footage of himself playing the game, which has since been viewed nearly 15 million times. Other popular YouTubers such as GameGrumps also posted DreadOut footage, securing millions more views and building awareness.

Five years after the game was launched, the studio received a call from Kimo Stamboel – half of the directorial team Mo Brothers – who said he wanted to make a big-screen movie based on the game.

The movie DreadOut was released in January 2019 in Indonesia and was seen by more than 800,000 cinema-goers – “a massive surprise”, Rachmad says. It was later screened in Singapore, Taiwan and South Korea. A few months after the film’s Indonesian premiere, the DreadOut team got another surprise when Netflix Southeast Asia sought the rights to stream the film.

“The success gave us, and myself, a sense of validation, that people actually liked and supported our ideas,” Rachmad says. And it gave them the confidence to take on other projects.

In February, Digital Happiness released DreadOut 2. Although it drew some criticism from foreign media, local gamers welcomed it with open arms. Pladidus, from JagatPlay, gives the developers marks for courage. They could have avoided risks and simply tinkered with the original game to assure sales, but instead “they added a semi open-world hub and they expanded the lore. So they were not staying stagnant, and I appreciate that”, he says.

Despite its commercial success, the original DreadOut was not without its critics. Most complaints were about the game’s frustrating technical bugs. A review on the website Hardcore Gamer stated: “DreadOut is plagued with poor design choices and a small budget.”

Yet Italian gaming website Multiplayer praised the game’s atmosphere as being “thick and scary” and called DreadOut “a trip that’s worth your time”.

Indonesian gamer and bank employee Noviar Akbar, 41, says the game has a creepy feel. “I could not sleep well for a few days after playing it.”

Rachmad says he cares about users’ opinions, even if they trash the game in public forums. “At the end of the day, they are our customers, and they are the ones paying to keep our company alive,” he says. “We’ll take it all on board and make adjustments, but we’ll keep the final decisions in our own hands as game developers.”