Part two of our special report on the Hong Kong international writers festival There was, sometimes, a certain kind of temperature in the room at the week-long 22nd Hong Kong International Writers Festival which I attended in March. China was not merely the elephant running hot and cold in that room: it was the room itself. China, always China, directing and instructing Hong Kong to perform as a kind of serf state.

During the week I was there, delegates of the National People’s Congress gathered in the similarly importantly capitalised Great Hall of the People in Beijing to re-elect Xi Jinping as president by the fairly convincing margin of 2952 to 0. "The Emperor," an outspoken audience member said mockingly of Xi, when I spoke with him at the festival after a panel discussion on Hong Kong's handling of Covid. He had a lot to say during that event. He was critical, scornful, loud. But he lowered his voice when he made his remark about Xi, and hunched his shoulders.

I left New Zealand on a Saturday. At Auckland International Airport, a copy of Xi's book The Governance of China Vol IV was ranked the 31st biggest seller at the airport bookstore. People read this junk? "Our compatriots in Hong Kong will certainly carry on their honourable tradition of loving the country and Hong Kong," Xi writes, "and strive for the rejuvenation of the Chinese nation shoulder to shoulder with the people of the rest of the country". I ambled to the downtown waterfront district on Hong Kong island on Sunday morning and saw Xi's brave new messaging reinforced by a massive billboard of a little girl standing in front of the bridge connecting Hong Kong to the Chinese mainland. It was titled, UNDERSTANDING BRINGS US TOGETHERNESS.

But togetherness has to be closely patrolled. Later that same day, on my way to the Star Ferry, that watery, sparkly rite of passage to and from Kowloon, the boats sometimes so quiet it felt as though they were being rowed, I came across a small gathering of women who were protesting against male violence. They announced a dance performance: a dozen women lined up, and danced to 'Flowers' by Miley Cyrus. It was an easily understood message of independence and a fun sight, given wider context – a Sunday in Hong Kong, China's serf state – by the presence of male police officers, taking names, taking notes. That same day, a rally calling for women's rights was cancelled after some of its supporters had received warnings from authorities against participating in the demonstration. You can dance, but you cannot march.

China imposed the crackdown laws on Hong Kong in 2020, after the violent pro-democracy 2019 protests. New powers of arrest have led to the jailing of protesters and media. One trial concluded while I was on the island. South China Morning Post: "Three core members of an alliance behind Hong Kong's Tiananmen Square vigil were found guilty yesterday of failing to assist a police investigation into the group's suspected violation of the national security law…The trio described the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown as the 'Tiananmen massacre', an expression the magistrate ruled was 'not neutral' and 'improper'."

How, then, would a literary festival – kind of the exact point of writing is freedom of expression – navigate the national security laws? Well, for a start, it had other things to think about, other pressing concerns. China preoccupies the attentions of Western media – China, always China – but the festival programme reflected a diversity of subjects. There were events devoted to the MH370 mystery (author Florence de Changy, who features on the Netflix documentary series examining MH370, lives in Hong Kong), Anglo-Indians and Eurasians in literature and film, supernatural fiction, financial markets, and other kind of literary or social matters.

But the subject of China was very often at the edges of things or right at the centre. I sometimes felt when reading the South China Morning Post over breakfast in my hotel ("No birds or domestic animals to be brought inside by guests") that parts of it were written in code, a kind of innuendo about Chinese state control and Hong Kong independence; maybe I was imagining it, and maybe I was reading too much into the lowered voice and note of caution whenever I asked about China. I spoke with one author who requested that her employer not be mentioned in our interview for fear of reprisals. I spoke with a journalist who talked about colleagues whose parents had been targeted by national security law officials, and then he said: "Is this an interview?" Hong Kong, off the record; but actually there were sessions at the festival where the subject of China, and China's surveillance state, were openly, freely discussed.

This was very much the case at the Soho House event featuring journalist Lulu Chen, author of Influence Empire: Inside the story of Tencent and China's Tech Ambition. She was chaired by Robin Harding, Asia editor of the Financial Times. He began by asking the audience of about 50: "How many of you are on WeChat?" He meant the Chinese messaging app described quite niftily at the Apple store as "more than a messaging and social media app – it is a lifestyle for one billion users across the world". Two-thirds of the audience said they were users. To which Chen coolly observed, "Well. There you go. You are among the billion people who have opted for convenience, and given up their privacy."

And yet she admired Tencent, the internet giant that operates WeChat, for its success, its achievement of "bursting China into the digital age". She talked about its culture, and the famous trek that the company's leadership committee were once directed to take through the Gobi Desert. "It shows the resolve to survive downfalls and competitors." She talked of staff working 9am to 9pm, six days a week, and teams being formed to compete with each other internally. And this: "Tencent thinks Facebook got it wrong in terms of how it monetises its business. It views Facebook as overmonetising its users. It's taken a lot of strength for Tencent not to do that; they don't bombard users. But they've made WeChat indispensable. They always wanted to be a utility, like electricity or water."

She also described WeChat as "the most effective monitoring system of people in China", and that it had been co-opted by the Chinese Communist Party. "The government was quite coy about it at first," she said, "and now it's quite open, for example, that its security apparatus uses WeChat to monitor journalists."

She was asked, "Does the company accept this?"

She replied, "It's a matter of survival. Even by pledging your alliance is not enough ... They are now in the embrace of the party."

*

Curiously, one of the rationalists – Western media call them apologists, or worse – for China's rule of law in Hong Kong is one of the original founders of the international writers festival. Former South China Morning Post journalist Nury Vittachi was instrumental in staging the first festival, in 2001, and attracting authors such as Hanif Kureishi and Vikram Seth. He is also the author of The Other Side of the Story: A Secret War in Hong Kong, which states that the 2019 pro-democracy protesters were actually "hired rioters" funded through the CIA. His thesis is that it had nothing to do with ordinary Hongkongers; it was everything to do with US agents of chaos. "We were marching not against China," Vitally writes, "but in favour of China being its best self”.

I suppose an equivalent to platforming Vitally might be a Hong Kong portrait of New Zealand which took the time to quote the wise opinions of Sean Plunkett. In any case I didn't see a copy of Vitacchi's book in my various traipsings around Hong Kong bookstores. But at Hong Kong Reader, a gorgeous little upstairs bookstore that I had a lot of trouble finding on Kowloon in the cheerfully shabby district of Mong Kok (it would help if the buildings were numbered), titles included City on the Edge: Hong Kong Under Chinese Rule by Ho Fung Hung, and City on Fire: The Fight for Hong Kong by Antony Dapiran. I was desperate to find a nearby bookstore with the ironic name Have A Nice Stay, founded by journalists who lost their jobs when the security laws closed down their newspapers; it's advertised as staying open till 3am on Friday nights, and I tried looking for it around midnight with no luck and sore feet.

The shop was written up as a beacon of intellectual and political freedoms in a feature story in the best source of independent news in Hong Kong, Hong Kong Free Press. One of the bookshop's founders told the online news outlet, “Even though I cannot work as a reporter – I lost that title – I hope that with this bookstore, we can promote journalistic values to all people in Hong Kong. When people know what journalism is, then the Fourth Estate can be empowered. The power of the media comes from citizens. [When] they believe in the media and they trust the media, then the media has the power to monitor other powers. So, it is very important that the citizens know… what journalism is. That is what I really want to carry out."

There are an estimated 50 independent bookstores in Hong Kong. I loved Hunter Bookstore in the cheerfully semi-shabby district of Sham Shui Po – to get there I walked past a row of stores selling toilets – and bought a range of seditious postcards. At Hunter and at other bookshops, I took note of titles such as Freedom: How We Lose It and How We Fight Back by Nathan Law, and Today Hong Kong, Tomorrow the World: What China's Crackdown Reveals About Its Plans to End Freedom Everywhere by Mark Clifford. Once again I got the impression that the subject of China, and China's surveillance state, were openly, freely discussed.

I think this was likely exceedingly naive. News report, from the Free Press: "Bookselling in Hong Kong became a potentially precarious profession in 2015, when five staff members of Causeway Bay Books went missing, eventually turning up in the custody of mainland Chinese authorities. The bookstore had been popular with Chinese tourists in search of titles considered contraband in the mainland."

After I returned to New Zealand, I interviewed Louisa Lim, author of the deeply felt and profoundly disturbing Indelible City: Dispossession and Defiance in Hong Kong. Her book was published in 2021. Since then, she said, the situation has got even worse – the state control, the stripping of freedoms. The modern history of Hong Kong is a history of occupations: British rule, Japan's invasion in World War II, Chinese rule since 1997. I asked Lim if China now or Japan then had a more harrowing impact on Hong Kong. China, she said.

Lim was in Hong Kong during the 1997 handover. She describes it as "a trade in human lives", and of Hong Kong "stranded between two great powers, the passive and neglected centre of attention with no clear role to play". It's acted out in an episode of The Crown, when Prince Charles is present at the handover. Hong Kongers have no clear role or even supporting role in the programme; it's all about the loss of a colony, or as the Queen Mother calls it, "The Great Chinese Takeaway." Charles is shown at the handover ceremony in the pouring rain. Louisa Lim was there, too. She writes of the central roles played by Charles, China's president, and governor Chris Patten "and his weeping blonde miniskirted daughters", and writes in Indelible City, "The Hong Kong people were mere spectators to their own fate".

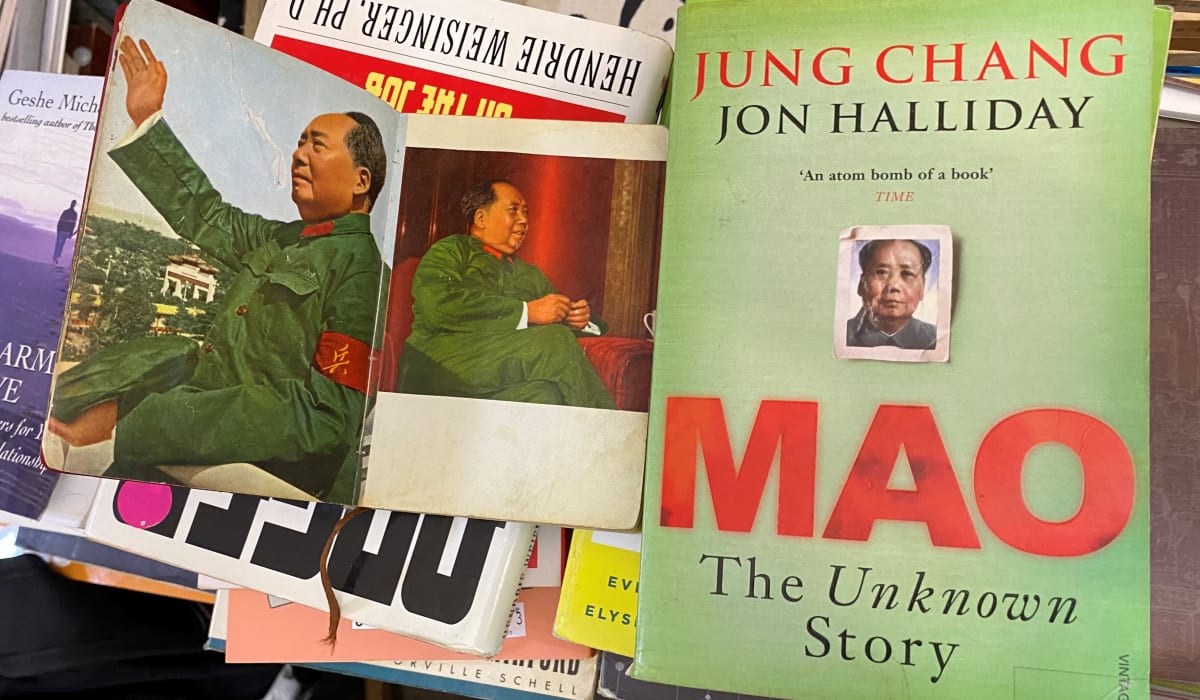

One of my happiest times in Hong Kong was at Flow, a second-hand bookstore which I found almost by chance. All I could tell from Google Maps is that I was close, very close; I looked up from my phone, and happened to see the shop's very small, very faint sign. I headed upstairs and into a perfect den of second-hand books spilling from the shelves – a crazy range of comics, records, magazines, fiction, and potent little mementos from history. There, for only $HK600, or roughly NZD$120, were beautiful 1960s first-edition copies of The Little Red Book, by Chairman Mao, each with colour photos of the Great Helmsman waving merrily and affectionately at the people he killed in the tens of millions. Steve Braunias travelled to Hong Kong with funding from the Asia New Zealand Foundation. This is the second of his week-long series on the Hong Kong international writers festival, following Monday's overview of the festival (includes poisonous snakes and a mandate rebel); tomorrow, a portrait of a Hong Kong literary genius.

Indelible City: Dispossession and Defiance in Hong Kong by Louisa Lim (Text, $37) is available in bookstores nationwide. She will appear the upcoming Auckland Writers Festival in an event chaired by Newsroom supremo Sam Sachdeva. His own book The China Tightrope: Navigating New Zealand's relationship with a world superpower is published by Allen & Unwin on May 23.