It was one of the greatest, silliest rock images of the early 2000s, and perfectly summed up The Darkness: their showboating lead singer Justin Hawkins, wearing a shiny catsuit, riding over the audience on the back of a white tiger stage prop, like a cross between Dave Lee Roth and Mowgli from The Jungle Book.

The Darkness were a loud, unashamed, spandex-clad rock band in the era of Coldplay and The White Stripes. Their 2003 debut album, Permission To Land, reached No.1 in the UK; its flagship single I Believe In A Thing Called Love went to No.2, and they even challenged Slade and Wizzard with their seasonal hit Christmas Time (Don’t Let The Bells End).

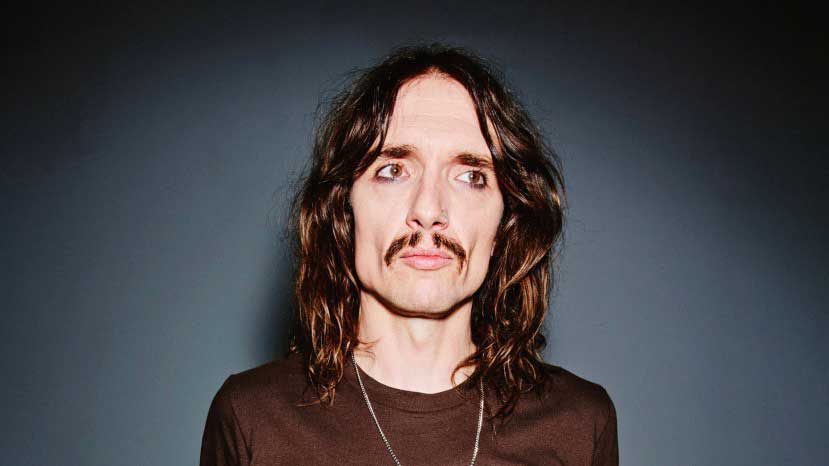

The brainchild of brothers Justin and guitarist Dan Hawkins, it was elder sibling Justin’s falsetto and five-octave range, his absurd humour and extravagant fashion sense that grabbed the headlines. Many seasoned rock fans got it, while others muttered disparagingly and went back to their old Gillan LPs. But The Darkness also crossed over to a pop audience who didn’t give two hoots for Deep Purple, never mind Gillan.

The Darkness underwent a messy separation in 2006, then reunited in 2011. Since then, Justin Hawkins has straddled the worlds of rock (with five more Top 20 Darkness albums), Saturday-night TV (via his stint on reality music show The Masked Singer) and YouTube, where his Justin Hawkins Rides Again channel has over half a million subscribers.

In October, The Darkness celebrated Permission To Land’s 20th anniversary with a bumper reissue and a birthday tour. Today, Justin Hawkins is talking to Classic Rock from his adopted home of Thurgau, in eastern Switzerland. He’s not the only émigré British rock star in town, though.

"I’m about an hour away from where Phil Collins lives," he divulges. "That’s why I’m here. It gets awkward since he’s taken out that injunction…"

It’s twenty years since the band’s debut album Permission To Land. How has it been going back to it again?

We are writing a new Darkness album, so now is a good time to listen to it. I like it, but I don’t feel like the same person that recorded it. But I tend to go through an identity crisis every seven to ten years. So that’s like two whole existences in my life.

Everything in The Darkness’s world seems accelerated, though. You split up after the second album then reunited five years later.

I think that’s because we weren’t equipped for all this. We came from normal working-class families that weren’t musical at all. But we were also brought up to never say no to any opportunity. It seems accelerated, but that’s generally what happens when you get offered opportunities and just say yes to everything.

How would people have described you as a teenager at school?

Sportsy. Clownish. Not part of the cool clique. Definitely different from the other kids. Nerdy, sensitive…

What was the first record you bought?

The first single was Joe Dolce’s Shaddup Your Face, followed by Shakin’ Stevens’s This Ole House. My dad had a lot of great records, though – Dire Straits, Queen, Bryan Adams. The first album I bought with my own money was Run DMC’s Raising Hell, which got me into Aerosmith and rock. There’s some nasty blues-rock playing on Raising Hell which is quite easy to pull off.

It makes a change from trying to copy Jimmy Page, Ritchie Blackmore, Eddie Van Halen etc.

I loved all that. But, growing up, musicians like that made it daunting to take up the guitar. There was something nasty and easy to do about Run DMC.

You funded the early Darkness by writing and performing radio and TV advertising jingles for brands and products including IKEA, HSBC and Mars bars. How much did that influence the band?

I wouldn’t say I have an encyclopaedic knowledge, but I have listened to an awful lot of music, so I know how it’s put together. I can recognise what influences some music, and go back to the original source. If an ad agency didn’t have the money for an existing track, they called me up to do something that sounded like it without us getting sued.

Which artists did you have to copy?

I did one that was supposed to sound like Survivor, one like Marc Bolan, Neil Diamond, John Barrie… After a while the agency were aware I was doing rock music of my own. So I went from being the guy they used for anything without a budget to the guy that does rock when there isn’t a budget.

You once said: “The whole reason we started The Darkness was out of defiance,” and that you “didn’t care about being cool.” In 2003 the group crossed over to the mainstream, but also made a lot of classic rock fans terribly cross.

We did. I remember The Darkness supporting Whitesnake in Ipswich just as we were coming up [May 2003]. This was before people knew we had an album of good songs. There was a bit of: “Are these guys taking the piss out of us?” For a minute it felt like we weren’t going to cross over, even to people who liked the same things we were influenced by. It was tough because we fell between two worlds. But I think we worked so hard that we dug ourselves out of it.

A lot of heavy rock is inherently funny/stupid, though, whether it’s meant to be or not.

Exactly. But the comedy stuff we edge towards isn’t like Spinal Tap or Steel Panther, it’s more surreal than that. It’s things like [70s actor and spokenword artist] Peter Wyngarde or the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band. I’m always trying to put dramatic monologues on our albums. With Permission To Land, people kept talking about how we sounded like AC/DC and Queen, but they didn’t mention William Shatner.

Black Shuck, from Permission To Land, was about a ghost dog local to East Anglia. American bands sing about LA or New York, so you sang about The Darkness’s home town, Lowestoft.

This is something my brother and I didn’t always agree on. Dan wanted us to be the biggest band in the world. He’s very ambitious. But I just had this instinct that if you write about things you know about, it doesn’t matter if they are very, very geographically specific. Problems in Lowestoft are the same as in any other town that size [laughs]. It would be ridiculous for us to do something urban. Not authentic at all. I mean, if I was doing a lyric about an illness, I’d be very specific about the symptoms.

What illness would the Darkness sing about, though? Something from the Middle Ages, like the Black Death?

Maybe Raynaud’s Disease [laughs]. That’s a horrible disease, isn’t it? It makes it difficult to play guitar.

Does your brother have a problem with the more tongue-in-cheek aspects of The Darkness, then?

I don’t think so. I think we both have one foot on each side of the line for it to work. The line is there to be danced upon. I reject anything too serious and he rejects anything too silly.

How many good Queen stories did you get out of Roy Thomas Baker when he produced the second Darkness album, 2005’s One Way Ticket To Hell… And Back?

I have heard a million Freddie stories, which I can’t possibly tell you, though. We spent twenty-four hours a day in Roy’s company and he was hilarious, wonderful. If we had an idea, Roy would take it as far as it could go. I played some stupid pan pipes thing on a synthesiser with a pan pipe setting. So Roy found the best pan pipe player in Peru. Some of my notes didn’t exist in pan pipe world, so they built a special pan pipe so he could play that.

Why did you leave the group after that second album?

I couldn’t be around The Darkness because of all the drinking and everything. It wouldn’t have been good for my recovery. I didn’t want to stop making music but I wanted to stop killing myself.

Is that why you took a break and formed a new group, Hot Leg?

Yes. I needed to do something where I was in charge and the people around me in Hot Leg weren’t all drinking. I think all of us in The Darkness could have done with some time off. It would have been good for our relationships and, yes, our mental health. But then someone says: “Do you want to do this TV show?” And you’ve already done ten on the run and you won’t have another day off for a month. “But fuck it, it’s TV, let’s do it.” That’s what it was like then. We didn’t take a moment.

You recently said that you used to drink like normal people, “but like two or three normal people” at the same time. You’ve been clean and sober for seventeen years now.

Yes, seventeen years. If I hadn’t gotten sober we wouldn’t have been having this conversation.

During the Darkness’s hiatus, Hot Leg made the album Red Light Fever, and Dan Hawkins’s new group, Stone Gods, released Silver Spoons & Broken Bones. Neither were big hits.

Meanwhile, Justin was great at playing Screaming Lord Sutch in the film Telstar: The Joe Meek Story but less great when bidding to represent the UK in the 2007 Eurovision Song Contest. Justin and soul singer Beverlie Brown’s duet They Don’t Make ‘Em Like They Used To Do wasn’t chosen. “I’ll be going for Eurovision every year,” he said at the time. “I don’t care what it takes.”

Instead, he and Dan reunited The Darkness and made 2012’s comeback album Hot Cakes. The group have weathered several line-up changes since, including the return of original bassist Frankie Poullain (who’d quit after Permission To Land), and the arrival of drummer Rufus Taylor, son of Queen drummer Roger.

Four more albums have followed, each one fusing Dan’s mighty riffs with Justin’s paint-peeling vocals, skewed humour (sample song titles: Japanese Prisoner Of Love, Rock And Roll Deserves To Die) and geographically-specific lyrics (see: Welcome Tae Glasgow, from 2021’s Motorheart). The Darkness still aren’t saying no to any opportunity

The Darkness were always going to get back together, weren’t they?

Dan and I had actually been writing together for a couple of years before we went back to doing it properly. We wanted to do all the touring a year later than we did, but it was Def Leppard who insisted we do the Download festival with them [in 2011]. They made us their main support and brokered that whole thing. That brought the timeline forward. We thought the longer we stayed away, the better [laughs].

Was it easier going back to the group sober and after a break?

No, it wasn’t easier. The first album we did together [Hot Cakes] was conflict-shy and we weren’t communicating effectively. We weren’t pissed off with each other, but we were being tentative around each other so as not to fuck it up.

Did the music suffer?

That attitude isn’t productive when writing songs. It should be a battle, everyone fighting for the things they believe in. It’s more fun, as long as you don’t forget that you all love each other. It’s easy to lose sight of that. If you really believe in something and they don’t, it’s tempting to say: “I am not working with you any more”.

In the original video for I Believe In A Thing Called Love you’re writhing around in your underpants. Do you ever get embarrassed?

Frankie [Poullain] thinks I am immune to it.

Is it arrogance?

I don’t know that it is. I was an early adopter of the idea that if things go badly wrong, it’s actually good. When I was eighteen – this would have been around 1993 – I was doing some live stuff opening for the better local bands, and it was just me, a drum machine and a guitar. I would go on and improvise – just start the machine and jam. I was just making shit up on the spot. The first time I did it, my friend also fired ping pong balls at me. That was our show. My point is, you can’t do that stuff if you feel embarrassed, or embarrassed by failure.

Did it go badly wrong?

If it went at all [laughs]. Everything goes wrong. I’m at the stage now where I will draw attention to the mistakes we make. Like, if my brother drops a note or his guitar fucks up, I will say, very loudly: “Dan Hawkins on electric guitar!” every time.

Many classic rock bands get trapped in an image. Their audience expects, say, Judas Priest to go on stage wearing leather, and not an old pair of jeans. Do you feel trapped by having to wear a catsuit?

No. But it’s funny when people who heard our first record and then stopped paying attention to our career come up to me now. They’ll say: “Oh, you should go back to wearing the catsuit.” I say: “I never stopped wearing the fucking catsuit. You just stopped paying attention. I’ve been wearing the catsuit for twenty-one years. How many more fucking years do I have to wear it?” Over the summer we did some festival shows with Guns N’ Roses, and I wore a business suit. I rocked up on stage in the suit I wore when I arrived at the festival.

Did you find that liberating?

Yes. I could put my hand in my trouser pocket and be nonchalant. I was topless, though. But I am definitely up for trying new stuff. Going forward, I will probably mix it up between experimenting and wearing traditional Justin Hawkins stage wear.

If someone hadn’t listened to The Darkness since I Believe In A Thing Called Love and Permission To Land, where should they start?

Easter Is Cancelled [released in 2019]. That’s definitely the one. It’s the nearest thing to a concept album we ever made, and I’m still proud of the whole foretelling-of-covid thing.

Wasn’t that a fluke?

Yes. There was a lyric in there: ‘Spreading disease so they can sell the cure.’ I also think the headline ‘Easter Is Cancelled’ was used at some point during lockdown. Some of our fans were like: “Yay! Told you! The Darkness are brilliant!” They saw it as vindication for their faith in us.

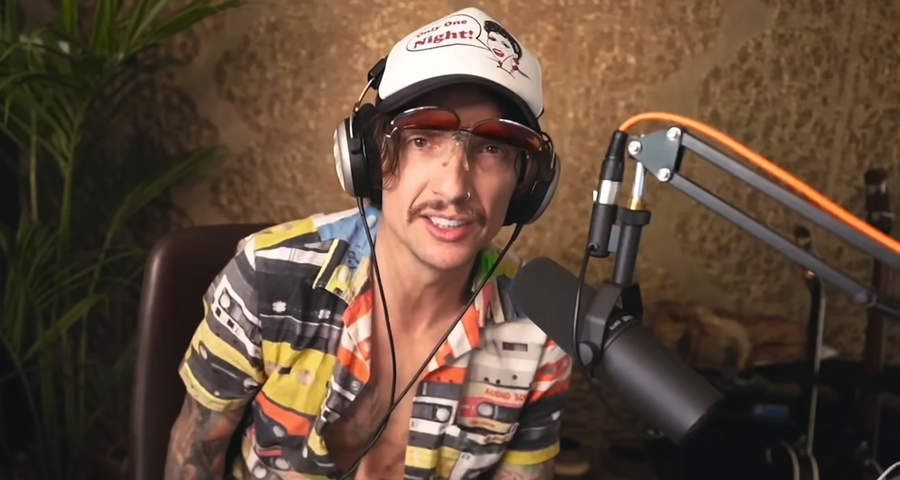

You’ve since become a very accessible kind of rock star. You have a dedicated Patreon following, who pay for subscriber-only content, and a YouTube channel, Justin Hawkins Rides Again.

I have become very accessible. Patreon was a brilliant thing for me to do when touring stopped during covid and I had all these expensive things to think about. I was doing music and keep-fit videos, and being prolific. But we helped each other out in a difficult, dark time. It’s like a friendship. I did a New Year’s Eve event online where I was DJ-ing and playing acoustic songs, and it was fucking great. My family and friends came down and nobody bothered them. The Patreon group feels like a community that doesn’t need me in it now.

You’re up to 500,000 subscribers on Justin Hawkins Rides Again.

I think it’s plateaued, but they are very engaged. I pivoted into it with the Patreon thing. My producer [Jenny May Finn] said we should do a YouTube channel. She thought I had a talent for it. So I half-heartedly went into it. Then it started to gain some traction.

Your followers also ask you to critique other artists’ performances, including Axl Rose and Dave Lee Roth. In 2006, Jon Bon Jovi said: “I hate The Darkness, fucking hate them.” You commented recently on his vocal problems. Do you ever censor yourself?

No, and I don’t listen to any of the stuff before I react either. That would be cheating. I never disrespect anybody, though. Jon Bon Jovi’s voice, for example, isn’t operational at the moment.

You’re having the conversation many Classic Rock readers are having among themselves.

Yes. I am sympathising too. Whether you are a fan or not doesn’t matter. Jon Bon Jovi has a distinctive way of delivering songs, and he has lost it, whether temporarily or permanently. I was offering solutions and explanations.

Have any of your comments on the channel ever backfired?

I recently expressed a preference for [Dire Straits’] Mark Knopfler’s guitar playing, because it’s expressive and has vibrato and some things [Red Hot Chili Peppers’] John Frusciante doesn’t. All I said was that I like Mark Knopfler using his guitar like a voice. It’s a more old-fashioned way of playing, but for me it’s more emotional. Then all these people piled in saying I was disrespecting John Frusciante. Oh, fuck off. Just fuck off! But I am not going to sit there and go: “Oh, I am sorry for having an opinion.” Listen to what I actually said. I didn’t disrespect anybody.

Do you ever worry about your voice becoming non-operational?

I don’t worry about that at all. Twenty years on and I am still doing the songs in the original key. But I also don’t feel like I sing the same way now. I think I sing better. Honestly, I don’t care if I lose my voice. It’s just life, isn’t it? What I do is physical as well, playing a heavy guitar, running around, doing headstands. That can only last so long. I am forty-eight now.

Would you drop songs down a semitone or do whatever other rock singers do as they get older?

I’ve performed I Believe In A Thing Called Love with other bands, and they’ve already dropped down a half-step [semitone], maybe because it makes the guitar sound better, and it’s easier for their singer. I find it harder to sing like that.

In 2020 you appeared on ITV’s The Masked Singer wearing a chameleon costume. One of the show’s judges, Davina McCall, heard your performance of Radiohead’s Creep and said: “This is good. Not a singer, but good.”

Yes! [laughs]. But, really, all you can hear with that helmet on is the sound of your appearance fee hitting your bank account. That really was all I cared about.

Did you enjoy the show at all?

It was… alright. It’s difficult to sing in a papiermâché hat, and it’s visually restrictive. You can only see out of a small aperture, a bit smaller than a letter box. It’s also discombobulating. The people that ran the thing were really nice to me, but it’s a lonely existence as you’re not allowed to talk to anyone or have any entourage with you in case they get recognised. Really, it was a handy injection of serious money when I needed it.

Would you do I’m A Celebrity Get Me Out Of Here! or Strictly Come Dancing? You’ve got to be a contender for Strictly; you must be in better nick than the average retired footballer.

I don’t know. If something comes along I will consider it on its artistic merit [makes the universal hand signal for rubbing bank notes together]. These things can be good for raising the band’s profile and reminding people I didn’t die. I nearly did, but I didn’t… No, but a lot of people thought I was dead or heading that way. I don’t need to do that at the moment, but if a TV opportunity came along it would have to be quite well paid.

Do you make good money from Christmas Time (Don’t Let The Bells End)?

No, but our streaming royalties are alright now. I have been watching this with interest. Something has changed, and our catalogue is doing better than it was. As a songwriter, your wealth is your catalogue, and real wealth is what builds when you’re not doing anything. Our revenue is up a lot. You notice it at Easter or around summertime, that’s when the money comes in. But Christmas Time was only a hit in the UK. It wasn’t even released in the States.

How serious were you about The Darkness breaking America twenty years ago?

We fell through the cracks [sighs]. In the UK we structured the campaign on the first record. Get Your Hands Off My Woman was the first single, because it was a good attention-grabbing sweary song, then Growing On Me, which was good for the mainstream, and then I Believe In A Thing Called Love, which is when Atlantic Records put some proper money into the video, and we made the next step up.

So what went wrong?

The American side of Atlantic had the opportunity to build it up in the same way, but they allowed the radio stations to pick the first single. Of course, they all went for I Believe In A Thing Called Love. The campaign was over before it began. There was nowhere for us to go.

So you didn’t bother?

No, I couldn’t be bothered by then [laughs]. I didn’t want to go there on the second record, so we didn’t. If the record company had a more patient approach to the States we could have done better. That was the first moment I thought: “Okay, yes, some of what you hear about the music trade is true.” But I do enjoy going there now.

Do you think America gets the humour?

Yes, because we are laughing at musical snobbery. America doesn’t suffer from that the way we do here. There’s more openness in the American music world – more collaborations and crossovers. Bands are less bitchy too, because it’s such a huge market it’s impossible for one band to claim it for themselves. When a band dominates in the UK, you get jealousy. For a minute it was us. You also have a fast track to your fan base now through the internet.

That wasn’t available twenty years ago.

Yes, and it’s a beautiful thing. My patrons are my focus group for everything now. If I was asked to do Strictly or another mainstream TV show, I would ask them: “Is this something which will make you cringe, or should I go for it?”

Finally, somebody once told us you make your own scent and you smell very nice.

What? Ha! Yes [looks a bit suspicious]. I have been known to dabble in that world. I don’t know which scent the person who told you this was talking about, though. They must have got in close and had a good sniff.

What do you smell like now, then?

Mmmm… [long pause] Something evoking old fur that’s been in a cupboard for a long time, with patchouli and some sweet stuff on the top, like coconut or even sugar. And on that note… A weird ending to the interview. Thank you.

The 20th anniversary Permission To Land… Again box set is out now via Warner Music. The Darkness are currently touring The UK and will head to Japan, New Zealand and Australia in the new year - dates and tickets.