The history of computers is fascinating because it's also the history of the world. Join us on a whirlwind tour of the great technological breakthroughs of the past few centuries, from Ada Lovelace to Alan Turing. Then we’ll bring you bang up to date, explaining the influence of Bill Gates and Steve Jobs, right up tothe current state of play with regard to artificial intelligence (AI) and quantum computing.

We'll also bust a few myths along the way. Who really created the first computer? Was it John Mauchly with ENIAC? Alan Turing with his theoretical Turing Machine? Konrad Zuse with the Z3? Or could it actually be Charles Babbage with his Difference and Analytical Engines?

We're keen to redress any gender imbalances, too. While the history of computing has been dominated by men (again, reflecting world history) many important contributions have also come from women. Not least Ada Lovelace, who some consider the first programmer, and the computer pioneer Grace Hopper.

But this is a timeline of key events in computing history, so let's start with the days of mechanical calculators and, yes, looms.

The origins of computing (16th to 19th century)

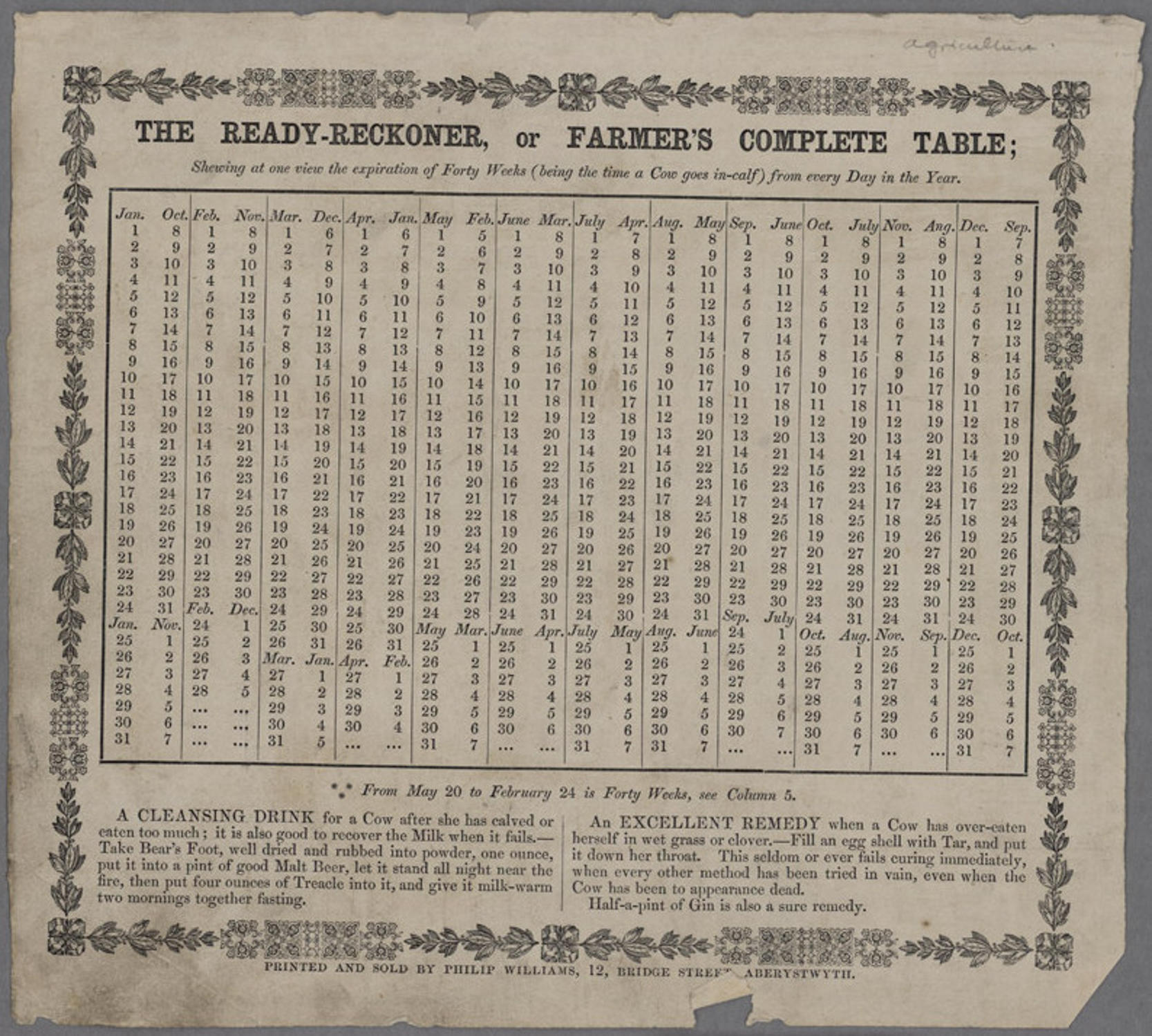

1570s — If you were a merchant, trader or farmer in the late 16th century, your computer of choice was a book full of ready-made calculations known as the “ready reckoner.” These books were particularly useful for calculating compound interest and remained popular right up until the 20th century. The only problem — and this became a big motivation for Charles Babbage — was that they often included mistakes.

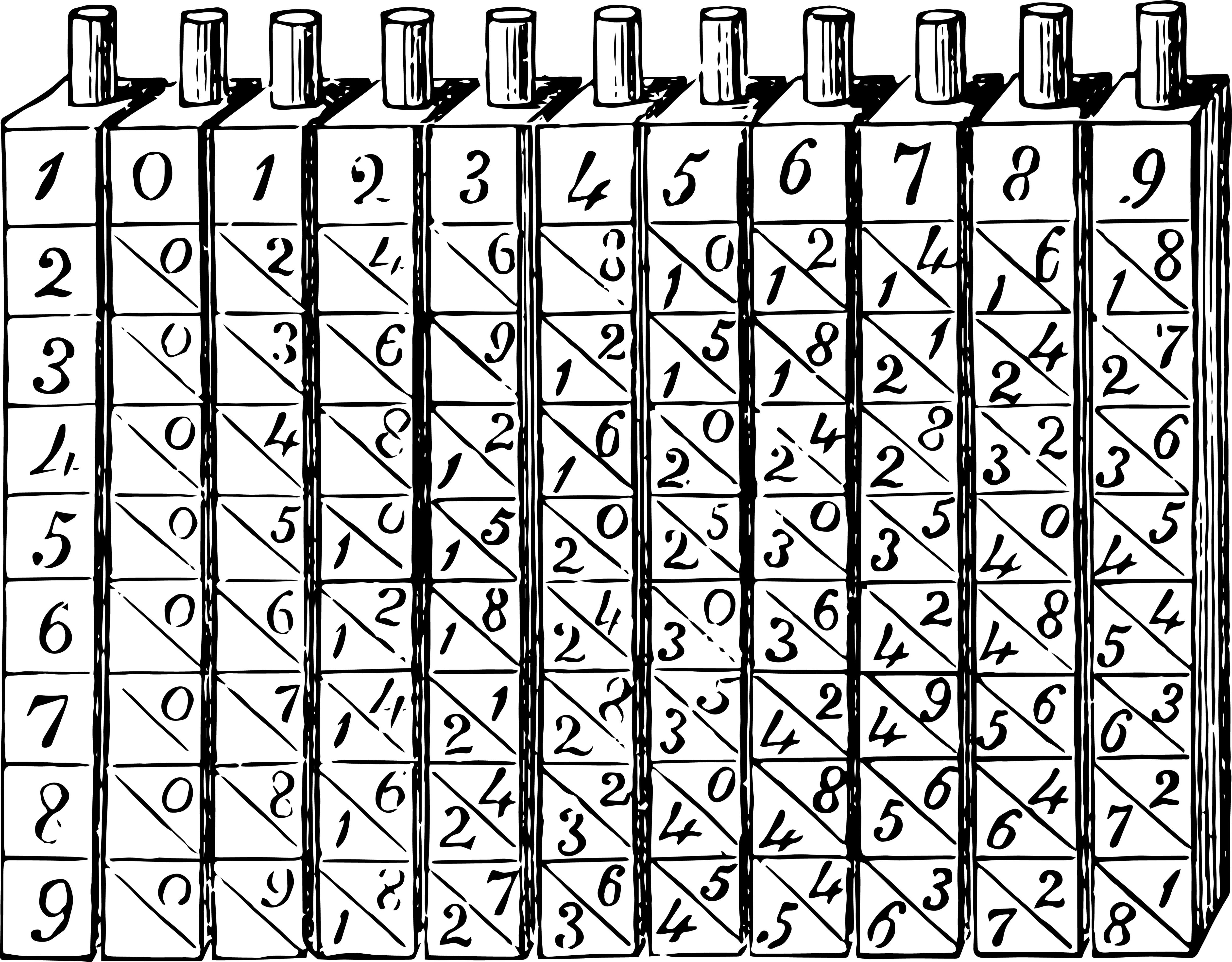

1617 — We've always longed for mechanical aids to help calculation, and the abacus (an invention dating back to 3000 B.C.) was a tool used for centuries. The first threat to its dominance came from the Scottish mathematician John Napier, who was also famous for inventing logarithms. In 1617, Napier showed how to multiply and divide any two numbers by using pre-printed rods with embedded multiplication tables within them. He called them Napier's bones.

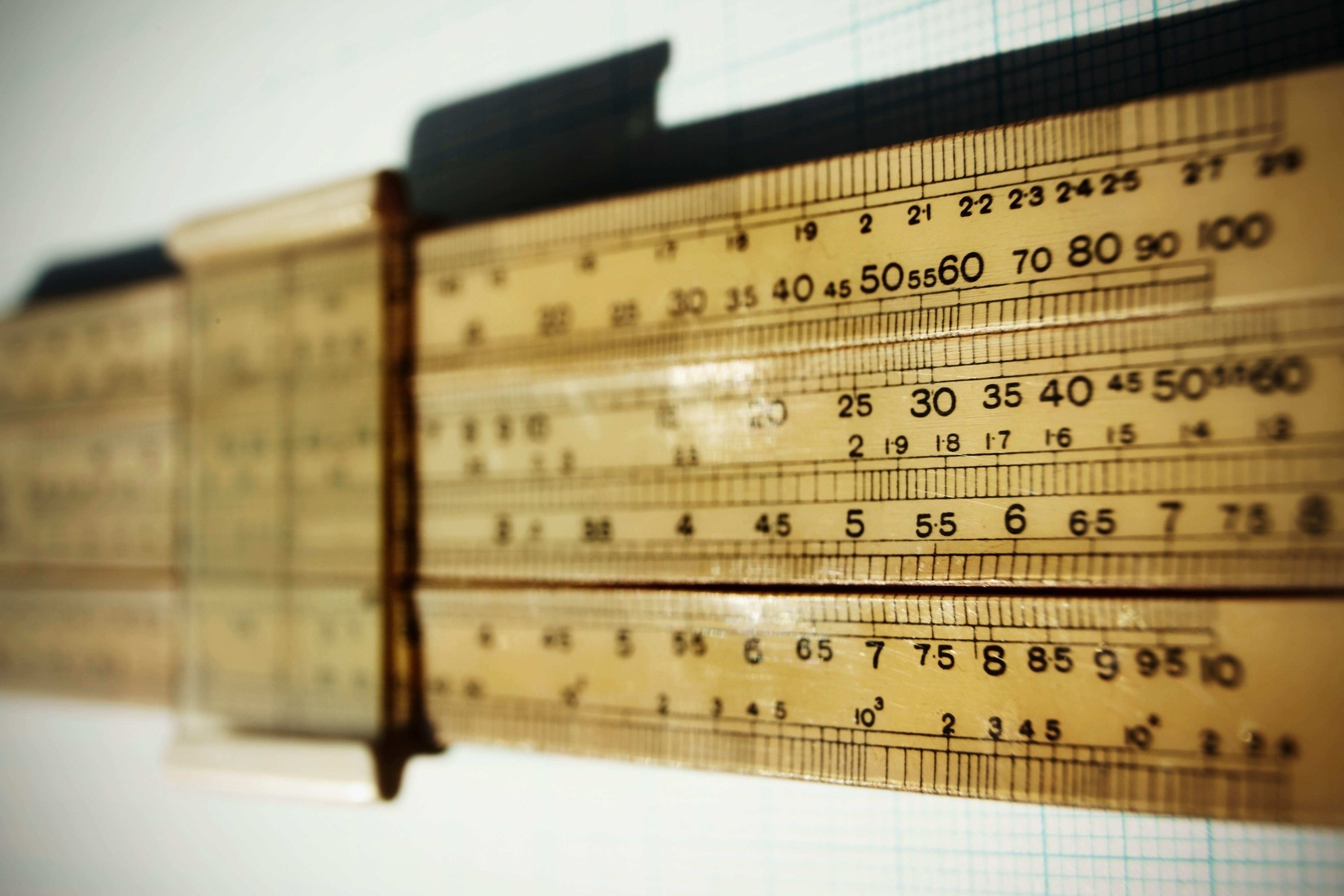

1622 — Isn't it always the way? You wait 46 centuries for an improvement on the abacus and then two come at once. English mathematician William Oughtred invented a ruler, consisting of a middle part sliding between upper and lower values, to add two logarithmic numbers to produce a number equal to their multiple's logarithm (log a + log b = log ab). But this wasn't a coincidence — Napier had already shown this result before, and English mathematician Edmund Gunter created a scale to exploit it in 1620 — meaning that Oughtred's slide rule simply mechanized the process. His tool remained popular until the birth of affordable electronic calculators in the late 20th century.

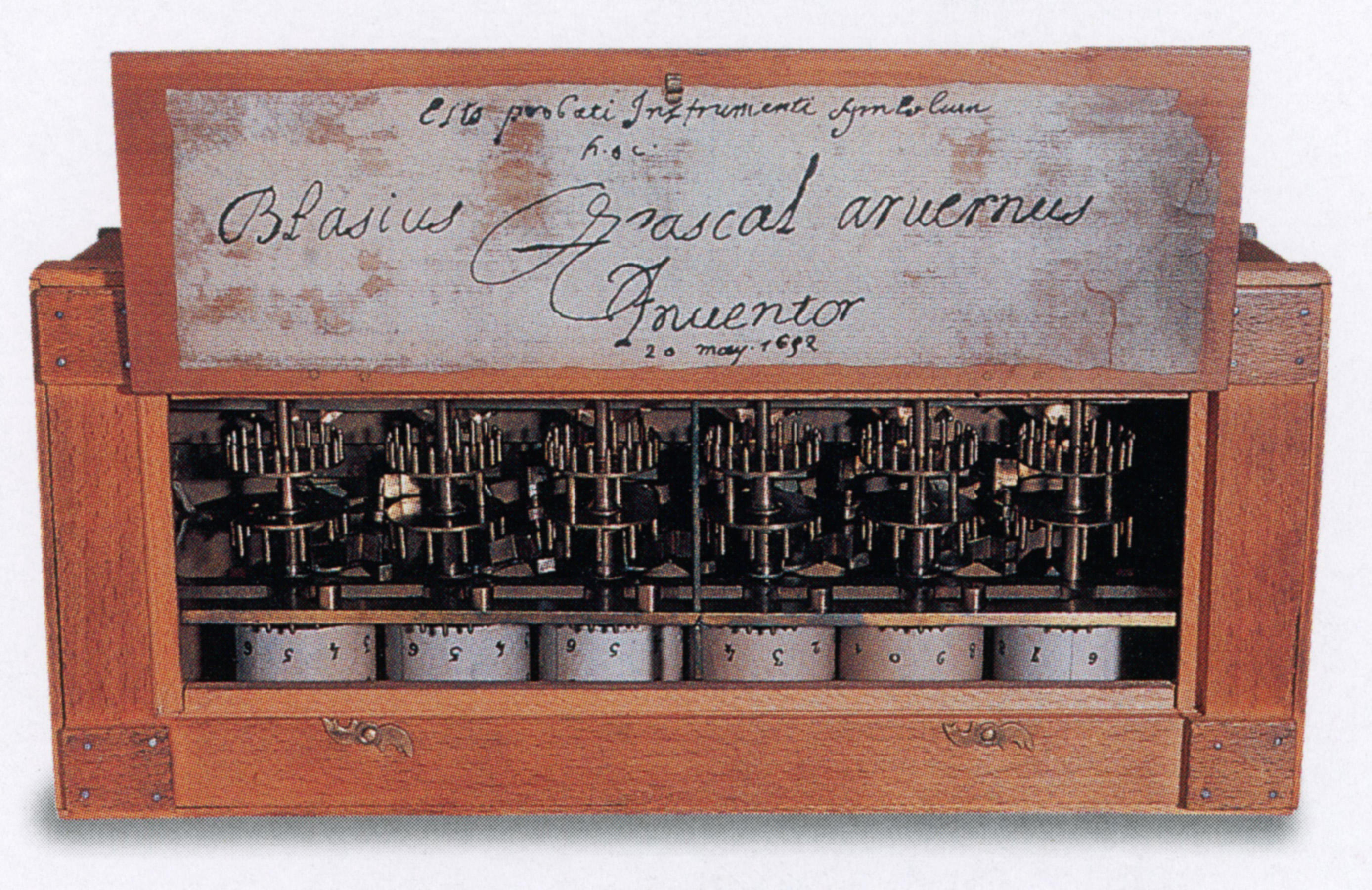

1642-44 — The father of legendary French mathematician and philosopher Blaise Pascal was a tax official, and that meant performing horrendous numbers of calculations. So his son invented a calculator, called the Pascaline, to automate addition and subtraction. You didn't need to understand the maths, merely adjust the dials. According to Britannica, Pascal built 50 Pascalines in the course of a decade, giving them a claim to be the “first business machine.”

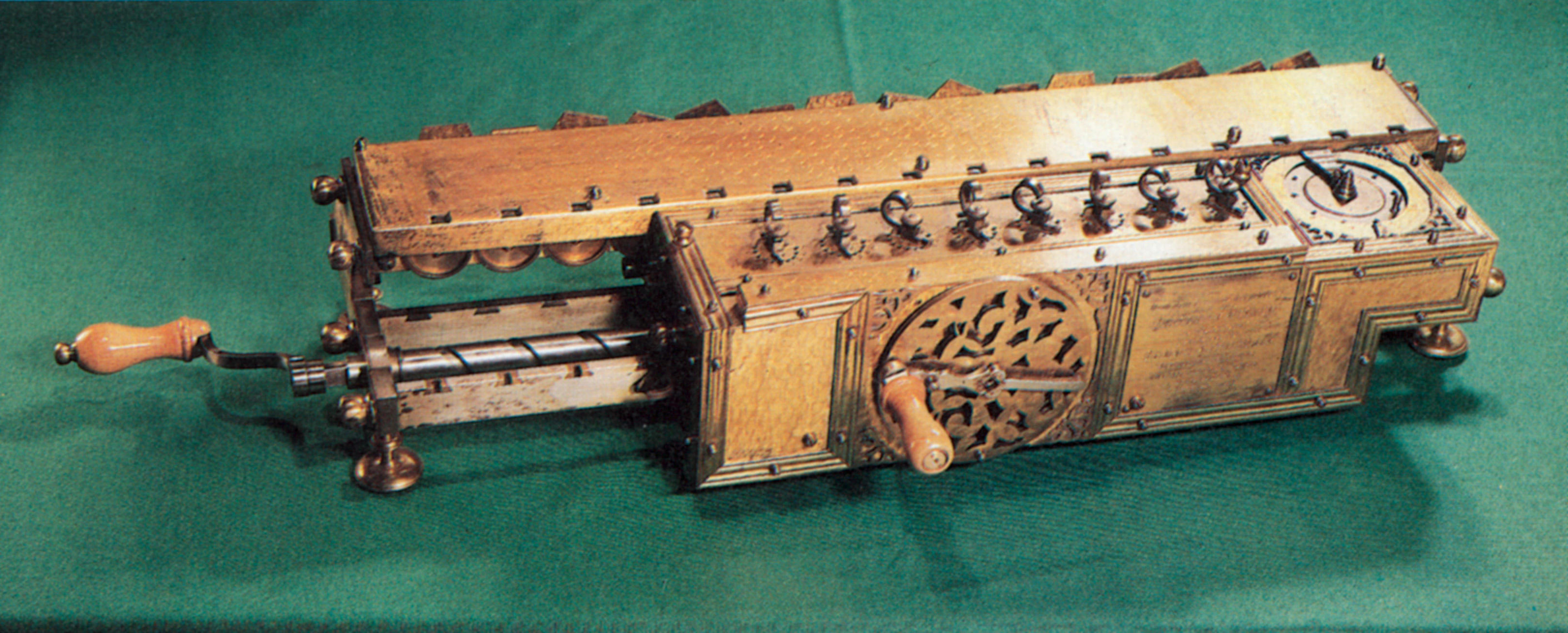

1673 —Aside from inventing calculus separately from Newton and his many other accomplishments, German polymath Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibniz also worked out how to improve the Pascaline so that it could also perform multiplication and division. His creation, the "Stepped Reckoner," relied on a stepped-drum mechanism to work. Yet the complexity of his design and the manufacturing limitations of the time meant Leibniz never built a satisfactory version in his lifetime. Nonetheless, his ideas would continue to influence mechanical calculators for two centuries.

1703 — Leibniz has also earned a separate entry on this list for creating binary notation — the zeroes and ones that underpin all modern computing. Inspired by Chinese hexagrams from around 900 B.C., Leibniz demonstrated how every whole number could be represented by a binary code consisting of 0s and 1s. It should be noted, though, that Spanish mathematician Juan Caramuel y Lobkowitz had introduced base-two numbers as a concept in his 1670 book “Mathesis biceps: vetus et nova” — he just didn't explicitly use 0s and 1s.

19th century

1801: Joseph Marie Jacquard, a French merchant and inventor invents a loom that uses punched wooden cards to automatically weave fabric designs. Early computers would use similar punch cards.

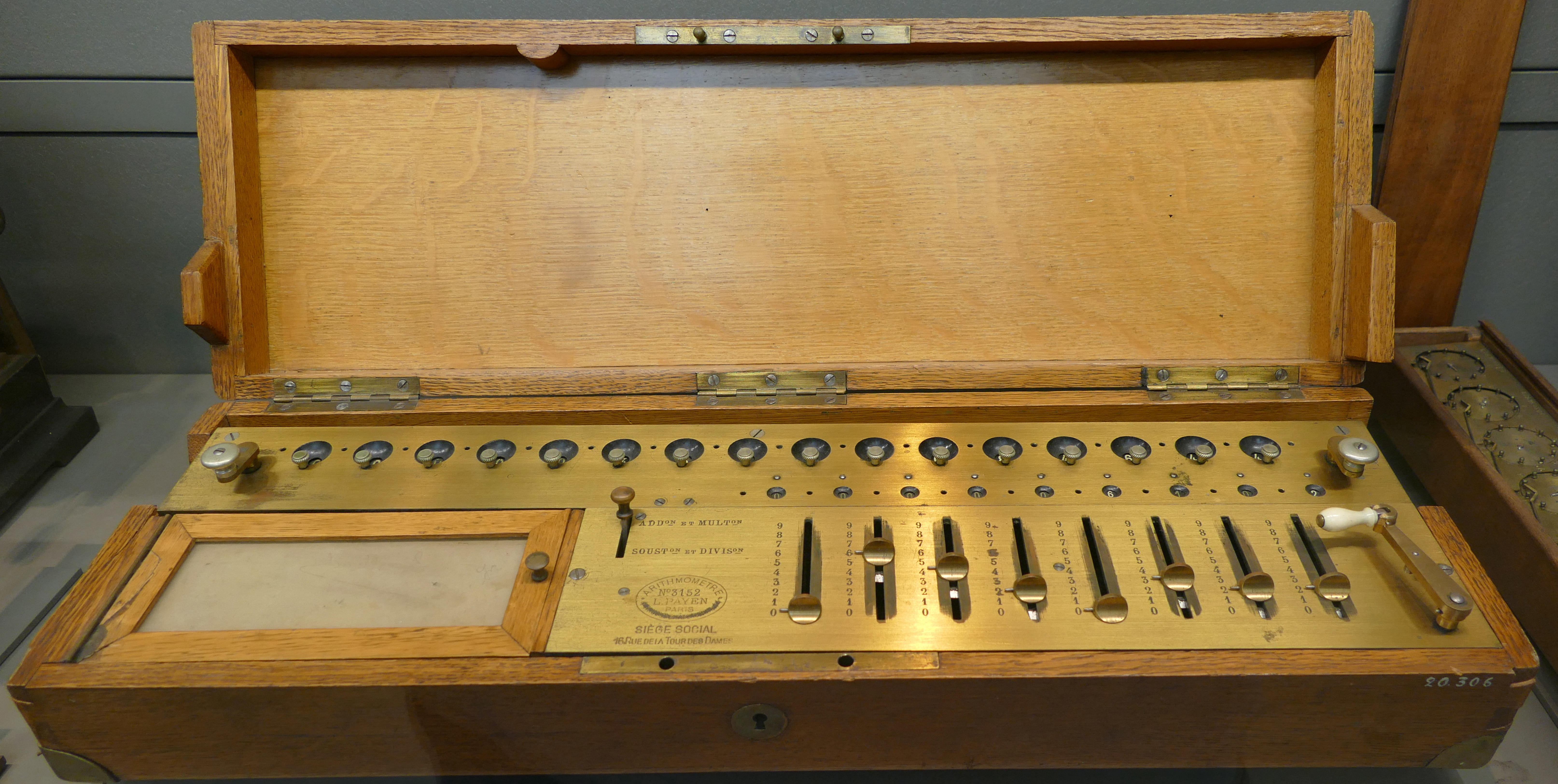

1820 — While many attempted to build Leibniz's Stepped Reckoner design, it took 150 years and the Industrial Revolution before the first mass-produced version arrived. It came in the form of French inventor Thomas de Colmar's Arithmometer, an elegant mix of brass and steel set in a box that was easy enough for non-experts to use. Over 2,000 units were sold and the design spawned countless imitations.

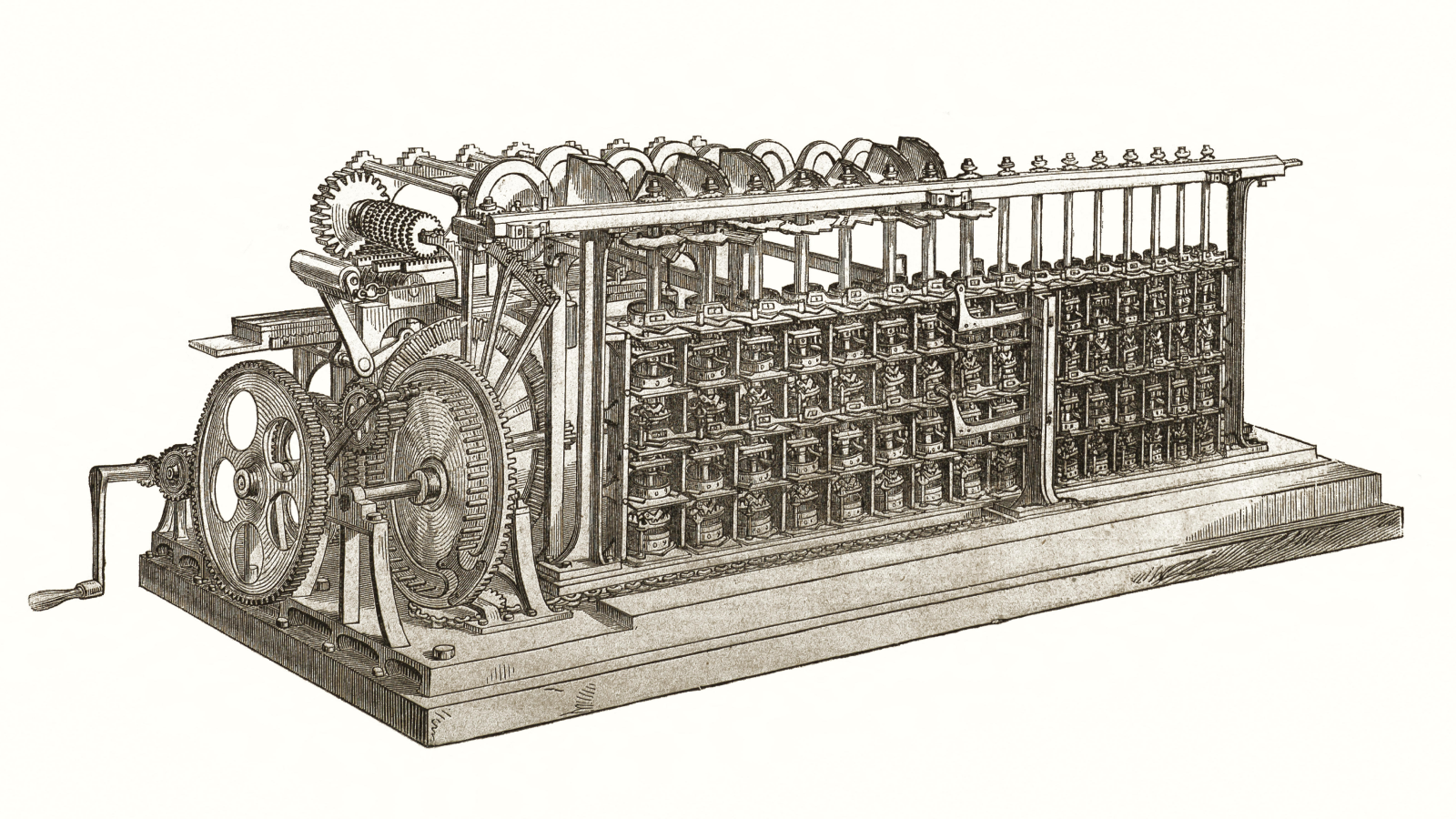

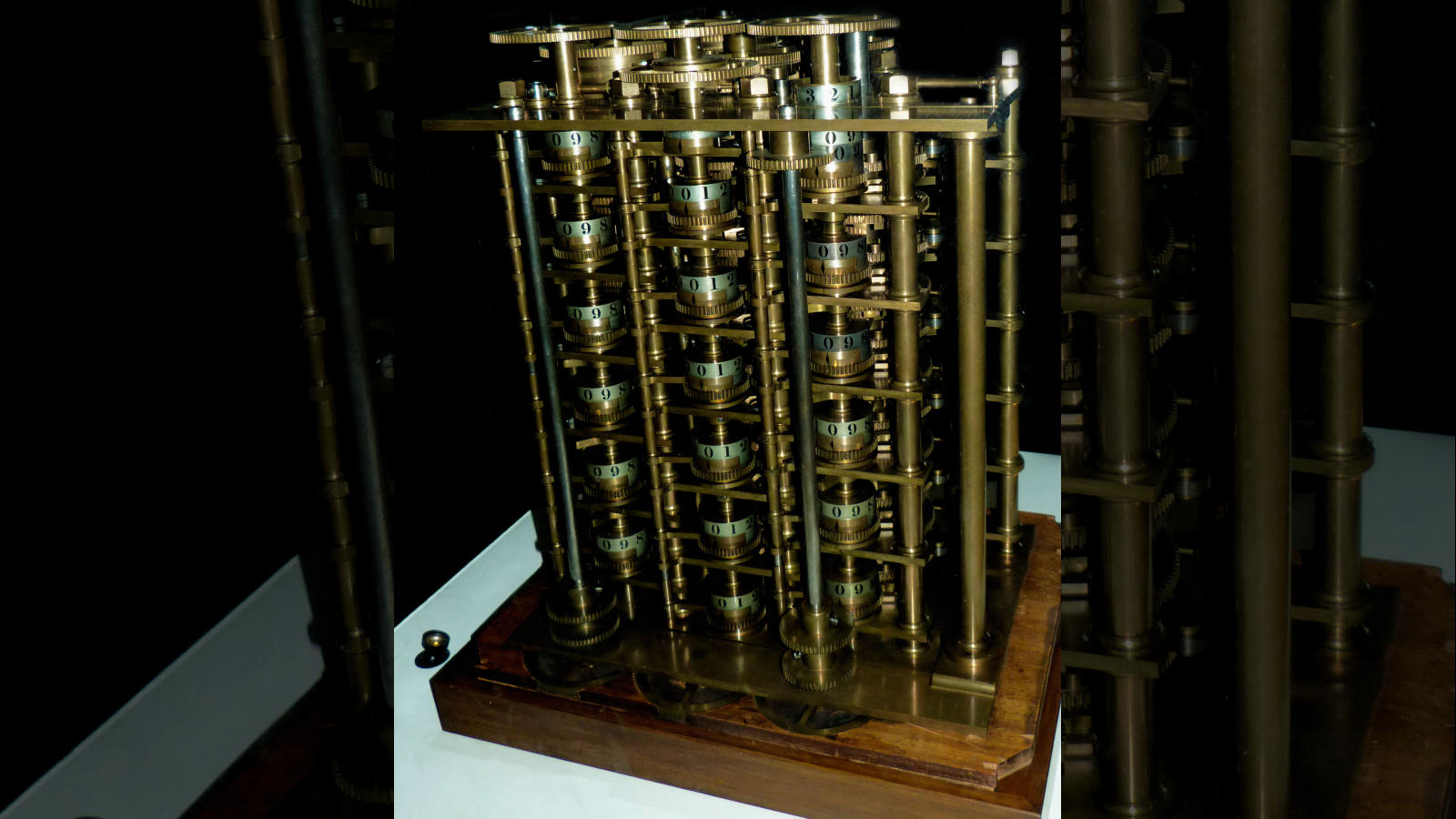

1822 — The mistakes often found in ready reckoners(printed books containing calculations) were a source of great irritation to Charles Babbage, an English inventor and mathematician born in 1791. Babbage created small mechanical calculators for his own use before going big in June 1822 — laying out the principles for a giant calculator that would automatically print tables based on differences. Babbage convinced the British government to back his project with £17,500 (roughly £1.5 million, or $2 million, in today's money). But despite all this money and nine years of effort from Babbage and the engineer Joseph Clement, the pair only produced one portion of the Difference Engine. It worked, but only represented “one-seventh of the complete design,” according to the Science Museum in London. With so little to show for its investment, the government withdrew its funding and Babbage's work on his engine ground to a halt.

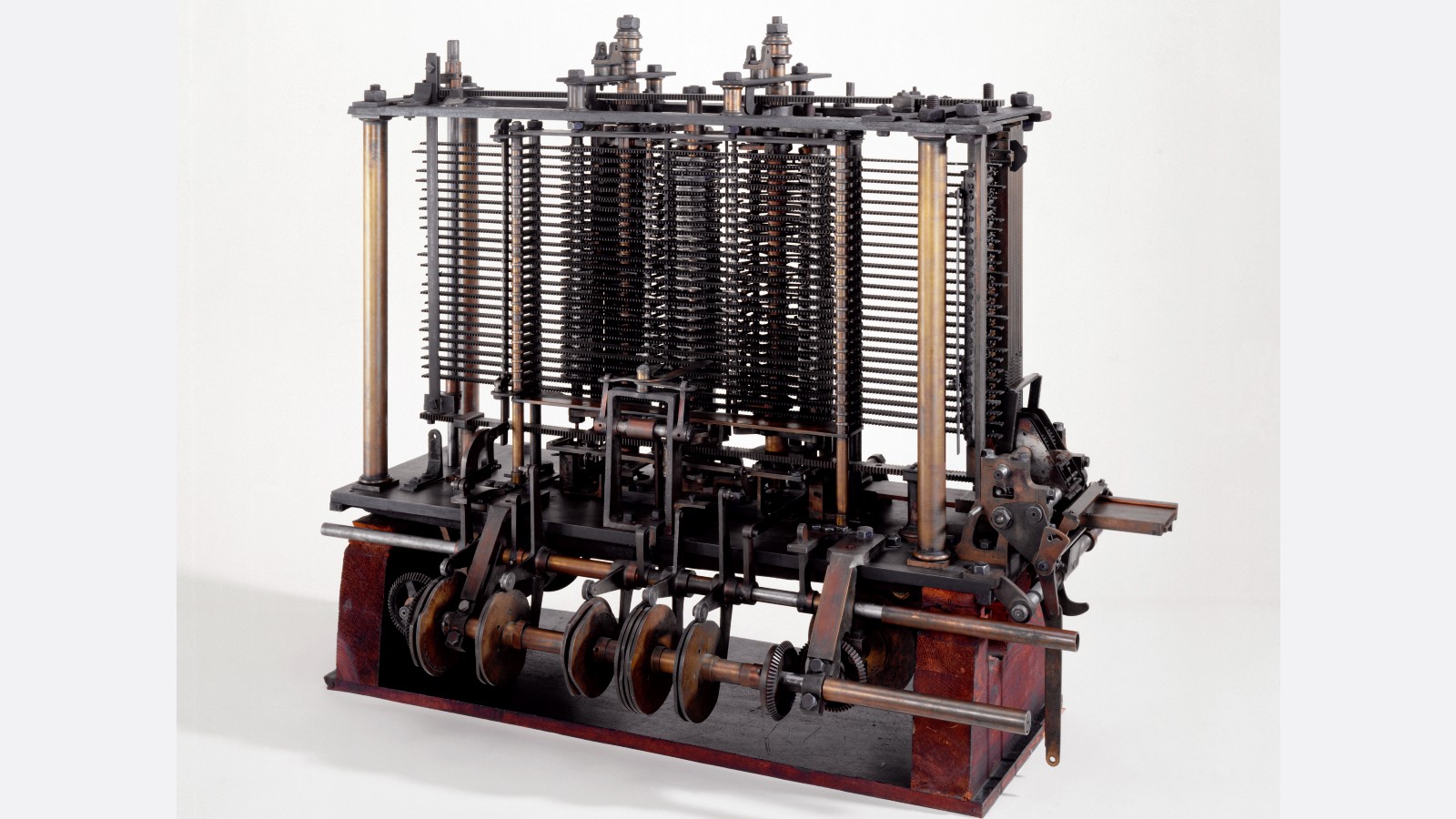

1833 — Charles Babbage was undeterred by the failure of the Difference Engine, however, immediately turning his attention to the more ambitious Analytical Engine. Some call this the first computer, as so many of its ideas remain in those we see today. For a start, the Analytical Engine was conceived to be general purpose, capable of performing any calculation (or what we would now call an algorithm). It contained a "Mill" to execute instructions (much like today's central processing units or CPUs) and a "Store," to hold numbers and calculations. Punched cards would tell the Analytical Engine what to do, and it also produced punched cards at the end of operations as output. There was even a basic form of conditional branching — think "do this if that happens." But if the machine’s ideas were ahead of its time, so was its complexity. A lack of finances and the machine’s dauntingly intricate components eventually caused Babbage to fall out with Clement, and hat the Analytical Engine was never built.

1848: Ada Lovelace, an English mathematician and the daughter of poet Lord Byron, writes the world's first computer program. According to Anna Siffert, a professor of theoretical mathematics at the University of Münster in Germany, Lovelace writes the first program while translating a paper on Babbage's Analytical Engine from French into English. "She also provides her own comments on the text. Her annotations, simply called "notes," turn out to be three times as long as the actual transcript," Siffert wrote in an article for The Max Planck Society. "Lovelace also adds a step-by-step description for computation of Bernoulli numbers with Babbage's machine — basically an algorithm — which, in effect, makes her the world's first computer programmer." Bernoulli numbers are a sequence of rational numbers often used in computation.

1853: Swedish inventor Per Georg Scheutz and his son Edvard design the world's first printing calculator. The machine is significant for being the first to "compute tabular differences and print the results," according to Uta C. Merzbach's book, "Georg Scheutz and the First Printing Calculator" (Smithsonian Institution Press, 1977).

1890: Herman Hollerith designs a punch-card system to help calculate the 1890 U.S. Census. The machine, saves the government several years of calculations, and the U.S. taxpayer approximately $5 million, according to Columbia University Hollerith later establishes a company that will eventually become International Business Machines Corporation (IBM).

Early 20th century

1931: At the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Vannevar Bush invents and builds the Differential Analyzer, the first large-scale automatic general-purpose mechanical analog computer, according to Stanford University.

1936: Alan Turing, a British scientist and mathematician, presents the principle of a universal machine, later called the Turing machine, in a paper called "On Computable Numbers…" according to Chris Bernhardt's book "Turing's Vision" (The MIT Press, 2017). Turing machines are capable of computing anything that is computable. The central concept of the modern computer is based on his ideas. Turing is later involved in the development of the Turing-Welchman Bombe, an electro-mechanical device designed to decipher Nazi codes during World War II, according to the UK's National Museum of Computing.

1937: John Vincent Atanasoff, a professor of physics and mathematics at Iowa State University, submits a grant proposal to build the first electric-only computer, without using gears, cams, belts or shafts.

1939: David Packard and Bill Hewlett found the Hewlett Packard Company in Palo Alto, California. The pair decide the name of their new company by the toss of a coin, and Hewlett-Packard's first headquarters are in Packard's garage, according to MIT.

1941: German inventor and engineer Konrad Zuse completes his Z3 machine, the world's earliest digital computer, according to Gerard O'Regan's book "A Brief History of Computing" (Springer, 2021). The machine was destroyed during a bombing raid on Berlin during World War II. Zuse fled the German capital after the defeat of Nazi Germany and later released the world's first commercial digital computer, the Z4, in 1950, according to O'Regan.

1941: Atanasoff and his graduate student, Clifford Berry, design the first digital electronic computer in the U.S., called the Atanasoff-Berry Computer (ABC). This marks the first time a computer is able to store information on its main memory, and is capable of performing one operation every 15 seconds, according to the book "Birthing the Computer" (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2016)

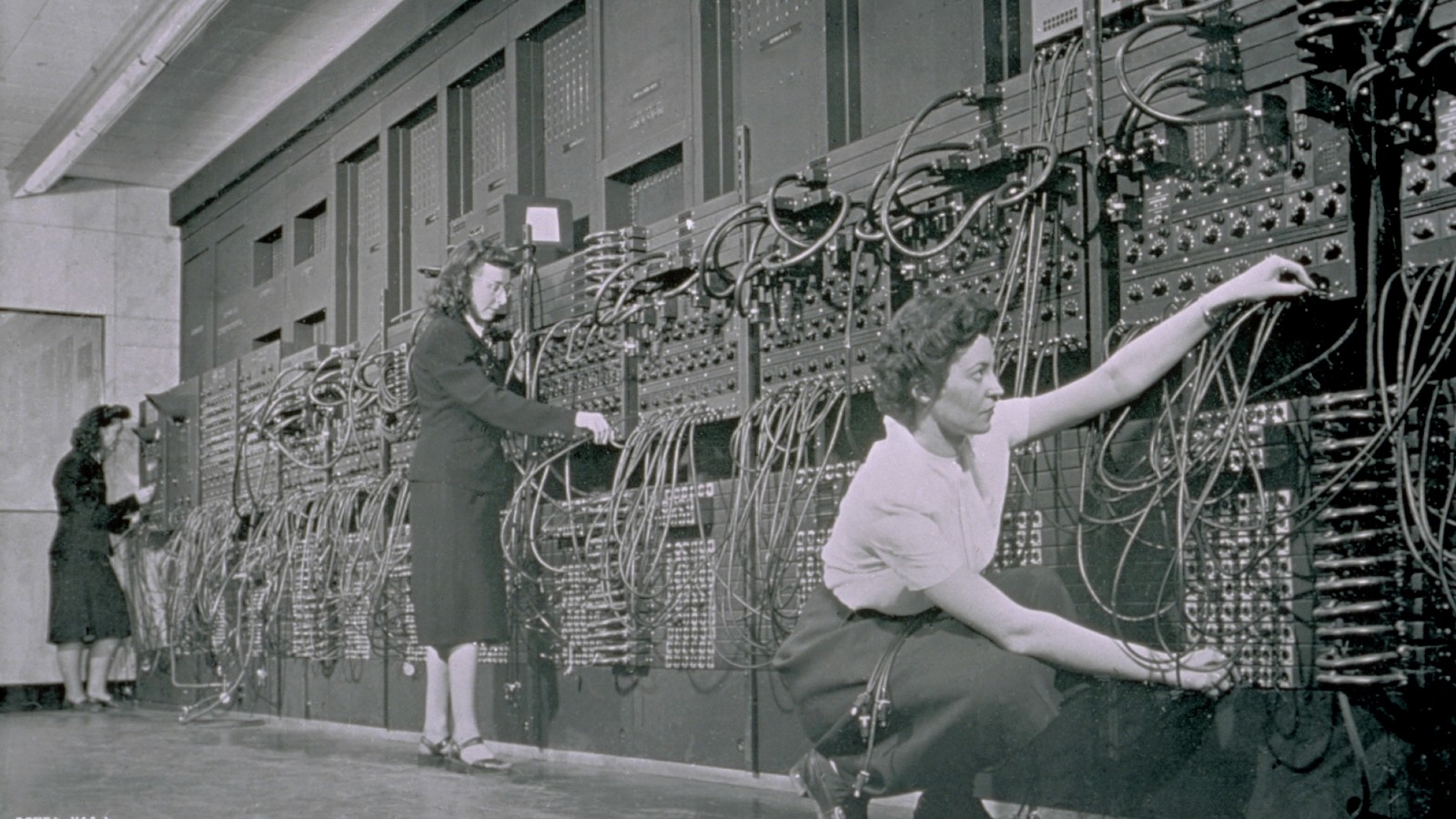

1945: Two professors at the University of Pennsylvania, John Mauchly and J. Presper Eckert, design and build the Electronic Numerical Integrator and Calculator (ENIAC). The machine is the first "automatic, general-purpose, electronic, decimal, digital computer," according to Edwin D. Reilly's book "Milestones in Computer Science and Information Technology" (Greenwood Press, 2003).

1946: Mauchly and Presper leave the University of Pennsylvania and receive funding from the Census Bureau to build the UNIVAC, the first commercial computer for business and government applications.

1947: William Shockley, John Bardeen and Walter Brattain of Bell Laboratories invent the transistor. They discover how to make an electric switch with solid materials and without the need for a vacuum.

1949: A team at the University of Cambridge develops the Electronic Delay Storage Automatic Calculator (EDSAC), "the first practical stored-program computer," according to O'Regan. "EDSAC ran its first program in May 1949 when it calculated a table of squares and a list of prime numbers," O'Regan wrote. In November 1949, scientists with the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), now called CSIRO, build Australia's first digital computer called the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research Automatic Computer (CSIRAC). CSIRAC is the first digital computer in the world to play music, according to O'Regan.

Late 20th century

1953: Grace Hopper develops the first computer language, which eventually becomes known as COBOL, which stands for COmmon, Business-Oriented Language according to the National Museum of American History. Hopper is later dubbed the "First Lady of Software" in her posthumous Presidential Medal of Freedom citation. Thomas Johnson Watson Jr., son of IBM CEO Thomas Johnson Watson Sr., conceives the IBM 701 EDPM to help the United Nations keep tabs on Korea during the war.

1954: John Backus and his team of programmers at IBM publish a paper describing their newly created FORTRAN programming language, an acronym for FORmula TRANslation, according to MIT.

1958: Jack Kilby and Robert Noyce unveil the integrated circuit, known as the computer chip. Kilby is later awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for his work.

1968: Douglas Engelbart reveals a prototype of the modern computer at the Fall Joint Computer Conference, San Francisco. His presentation, called "A Research Center for Augmenting Human Intellect" includes a live demonstration of his computer, including a mouse and a graphical user interface (GUI), according to the Doug Engelbart Institute. This marks the development of the computer from a specialized machine for academics to a technology that is more accessible to the general public.

1969: Ken Thompson, Dennis Ritchie and a group of other developers at Bell Labs produce UNIX, an operating system that made "large-scale networking of diverse computing systems — and the internet — practical," according to Bell Labs.. The team behind UNIX continued to develop the operating system using the C programming language, which they also optimized.

1970: The newly formed Intel unveils the Intel 1103, the first Dynamic Access Memory (DRAM) chip.

1971: A team of IBM engineers led by Alan Shugart invents the "floppy disk," enabling data to be shared among different computers.

1972: Ralph Baer, a German-American engineer, releases Magnavox Odyssey, the world's first home game console, in September 1972 , according to the Computer Museum of America. Months later, entrepreneur Nolan Bushnell and engineer Al Alcorn with Atari release Pong, the world's first commercially successful video game.

1973: Robert Metcalfe, a member of the research staff for Xerox, develops Ethernet for connecting multiple computers and other hardware.

1977: The Commodore Personal Electronic Transactor (PET), is released onto the home computer market, featuring an MOS Technology 8-bit 6502 microprocessor, which controls the screen, keyboard and cassette player. The PET is especially successful in the education market, according to O'Regan.

1975: The magazine cover of the January issue of "Popular Electronics" highlights the Altair 8080 as the "world's first minicomputer kit to rival commercial models." After seeing the magazine issue, two "computer geeks," Paul Allen and Bill Gates, offer to write software for the Altair, using the new BASIC language. On April 4, after the success of this first endeavor, the two childhood friends form their own software company, Microsoft.

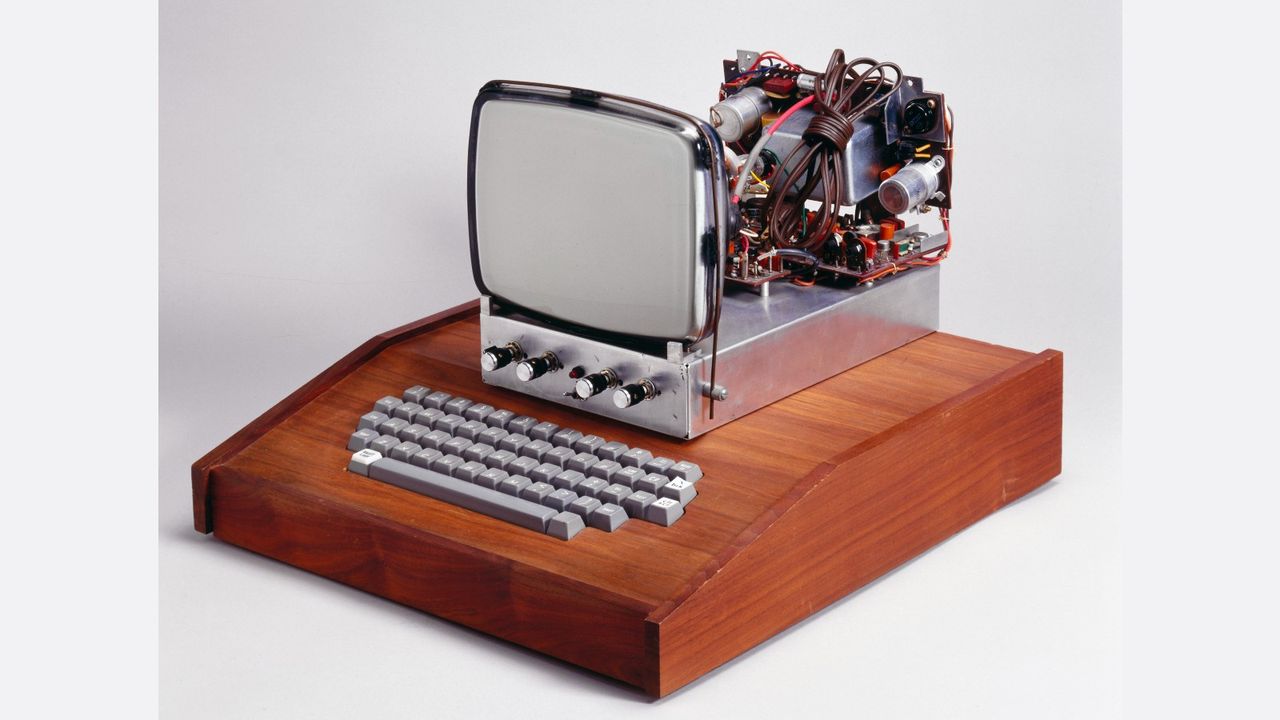

1976: Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak co-found Apple Computer on April Fool's Day. They unveil Apple I, the first computer with a single-circuit board and ROM (Read Only Memory), according to MIT.

1977: Radio Shack began its initial production run of 3,000 TRS-80 Model 1 computers — disparagingly known as the "Trash 80" — priced at $599, according to the National Museum of American History. Within a year, the company took 250,000 orders for the computer, according to the book "How TRS-80 Enthusiasts Helped Spark the PC Revolution" (The Seeker Books, 2007).

1977: The first West Coast Computer Faire is held in San Francisco. Jobs and Wozniak present the Apple II computer at the Faire, which includes color graphics and features an audio cassette drive for storage.

1978: VisiCalc, the first computerized spreadsheet program is introduced.

1979: MicroPro International, founded by software engineer Seymour Rubenstein, releases WordStar, the world's first commercially successful word processor. WordStar is programmed by Rob Barnaby, and includes 137,000 lines of code, according to Matthew G. Kirschenbaum's book "Track Changes: A Literary History of Word Processing" (Harvard University Press, 2016).

1981: "Acorn," IBM's first personal computer, is released onto the market at a price point of $1,565, according to IBM. Acorn uses the MS-DOS operating system from Microsoft. Optional features include a display, printer, two diskette drives, extra memory, a game adapter and more.

1983: The Apple Lisa, standing for "Local Integrated Software Architecture" but also the name of Steve Jobs' daughter, according to the National Museum of American History (NMAH), is the first personal computer to feature a GUI. The machine also includes a drop-down menu and icons. Also this year, the Gavilan SC is released and is the first portable computer with a flip-form design and the very first to be sold as a "laptop."

1984: The Apple Macintosh is announced to the world during a Superbowl advertisement. The Macintosh is launched with a retail price of $2,500, according to the NMAH.

1985: As a response to the Apple Lisa's GUI, Microsoft releases Windows in November 1985, the Guardian reported. Meanwhile, Commodore announces the Amiga 1000.

1989: Tim Berners-Lee, a British researcher at the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN), submits his proposal for what would become the World Wide Web. His paper details his ideas for Hyper Text Markup Language (HTML), the building blocks of the Web.

1993: The Pentium microprocessor advances the use of graphics and music on PCs.

1996: Sergey Brin and Larry Page develop the Google search engine at Stanford University.

1997: Microsoft invests $150 million in Apple, which at the time is struggling financially. This investment ends an ongoing court case in which Apple accused Microsoft of copying its operating system.

1999: Wi-Fi, the abbreviated term for "wireless fidelity" is developed, initially covering a distance of up to 300 feet (91 meters) Wired reported.

21st century

2001: Mac OS X, later renamed OS X then simply macOS, is released by Apple as the successor to its standard Mac Operating System. OS X goes through 16 different versions, each with "10" as its title, and the first nine iterations are nicknamed after big cats, with the first being codenamed "Cheetah," TechRadar reported.

2003: AMD's Athlon 64, the first 64-bit processor for personal computers, is released to customers.

2004: The Mozilla Corporation launches Mozilla Firefox 1.0. The Web browser is one of the first major challenges to Internet Explorer, owned by Microsoft. During its first five years, Firefox exceeded a billion downloads by users, according to the Web Design Museum.

2005: Google buys Android, a Linux-based mobile phone operating system

2006: The MacBook Pro from Apple hits the shelves. The Pro is the company's first Intel-based, dual-core mobile computer.

2009: Microsoft launches Windows 7 on July 22. The new operating system features the ability to pin applications to the taskbar, scatter windows away by shaking another window, easy-to-access jumplists, easier previews of tiles and more, TechRadar reported.

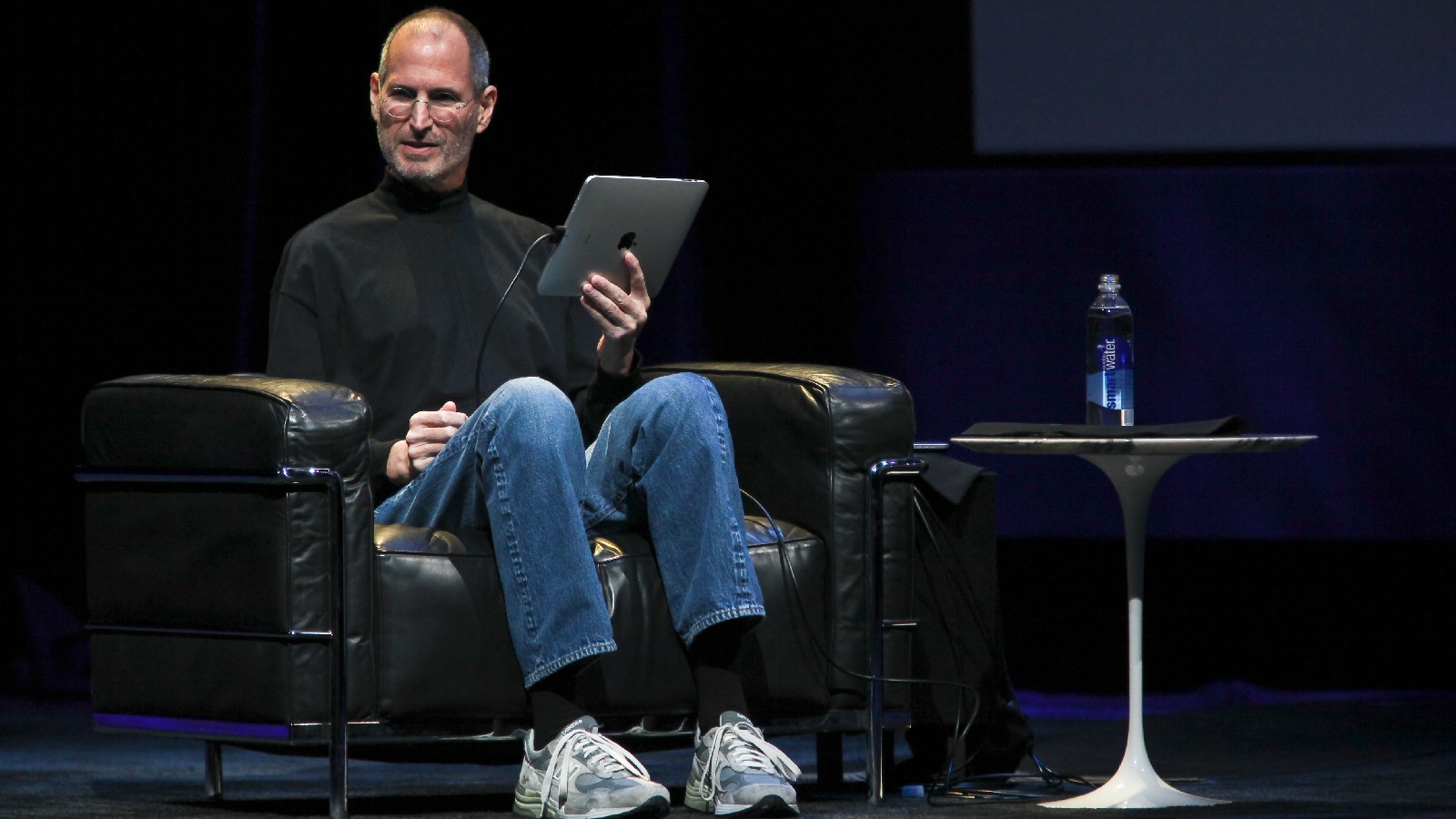

2010: The iPad, Apple's flagship handheld tablet, is unveiled.

2011: Google releases the Chromebook, which runs on Google Chrome OS.

2015: Apple releases the Apple Watch. Microsoft releases Windows 10.

2016: The first reprogrammable quantum computer was created. "Until now, there hasn't been any quantum-computing platform that had the capability to program new algorithms into their system. They're usually each tailored to attack a particular algorithm," said study lead author Shantanu Debnath, a quantum physicist and optical engineer at the University of Maryland, College Park.

2017: The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) is developing a new "Molecular Informatics" program that uses molecules as computers. "Chemistry offers a rich set of properties that we may be able to harness for rapid, scalable information storage and processing," Anne Fischer, program manager in DARPA's Defense Sciences Office, said in a statement. "Millions of molecules exist, and each molecule has a unique three-dimensional atomic structure as well as variables such as shape, size, or even color. This richness provides a vast design space for exploring novel and multi-value ways to encode and process data beyond the 0s and 1s of current logic-based, digital architectures."

2019: A team at Google became the first to demonstrate quantum supremacy — creating a quantum computer that could feasibly outperform the most powerful classical computer — albeit for a very specific problem with no practical real-world application. The described the computer, dubbed "Sycamore" in a paper that same year in the journal Nature. Achieving quantum advantage – in which a quantum computer solves a problem with real-world applications faster than the most powerful classical computer — is still a ways off.

2022: The first exascale supercomputer, and the world's fastest, Frontier, went online at the Oak Ridge Leadership Computing Facility (OLCF) in Tennessee. Built by Hewlett Packard Enterprise (HPE) at the cost of $600 million, Frontier uses nearly 10,000 AMD EPYC 7453 64-core CPUs alongside nearly 40,000 AMD Radeon Instinct MI250X GPUs. This machine ushered in the era of exascale computing, which refers to systems that can reach more than one exaFLOP of power – used to measure the performance of a system. Only one machine – Frontier – is currently capable of reaching such levels of performance. It is currently being used as a tool to aid scientific discovery.

FAQs

What is the first computer in history?

Charles Babbage's Difference Engine, designed in the 1820s, is considered the first "mechanical" computer in history, according to the Science Museum in the U.K. Powered by steam with a hand crank, the machine calculated a series of values and printed the results in a table.

What are the five generations of computing?

The "five generations of computing" is a framework for assessing the entire history of computing and the key technological advancements throughout it.

The first generation, spanning the 1940s to the 1950s, covered vacuum tube-based machines. The second then progressed to incorporate transistor-based computing between the 50s and the 60s. In the 60s and 70s, the third generation gave rise to integrated circuit-based computing. We are now in between the fourth and fifth generations of computing, which are microprocessor-based and AI-based computing.

What is the most powerful computer in the world?

As of November 2023, the most powerful computer in the world is the Frontier supercomputer. The machine, which can reach a performance level of up to 1.102 exaFLOPS, ushered in the age of exascale computing in 2022 when it went online at Tennessee's Oak Ridge Leadership Computing Facility (OLCF)

There is, however, a potentially more powerful supercomputer waiting in the wings in the form of the Aurora supercomputer, which is housed at the Argonne National Laboratory (ANL) outside of Chicago. Aurora went online in November 2023. Right now, it lags far behind Frontier, with performance levels of just 585.34 petaFLOPS (roughly half the performance of Frontier), although it's still not finished. When work is completed, the supercomputer is expected to reach performance levels higher than 2 exaFLOPS.

What was the first killer app?

Killer apps are widely understood to be those so essential that they are core to the technology they run on. There have been so many through the years – from Word for Windows in 1989 to iTunes in 2001 to social media apps like WhatsApp in more recent years

Several pieces of software may stake a claim to be the first killer app, but there is a broad consensus that VisiCalc, a spreadsheet program created by VisiCorp and originally released for the Apple II in 1979, holds that title. Steve Jobs even credits this app for propelling the Apple II to become the success it was, according to co-creator Dan Bricklin.

Additional resources

- Fortune: A Look Back At 40 Years of Apple

- The New Yorker: The First Windows

- "A Brief History of Computing" by Gerard O'Regan (Springer, 2021)