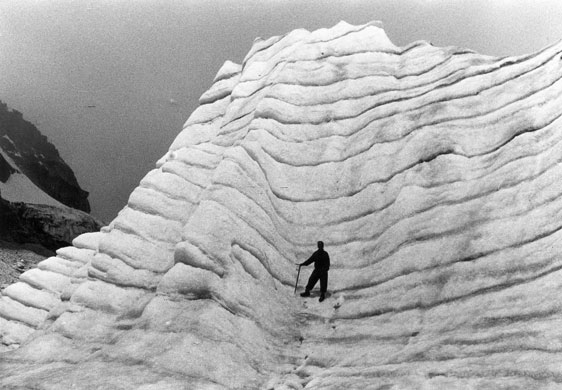

Bottom: By 2007, the Imja lake had grown to around one kilometre long with an average depth of 42 metres, and contained more than 35m cubic metres of water. The Imja glacier is retreating at an average rate of 74 metres a year, and is thought to be the fastest retreating glacier in the Himalayas. Photograph: The Mountain Institute/Erwin Schneider/Alton Byers

Bottom: Ama Dablam and Imja valley photographed from the same point in 2007. Warmer temperatures have contributed to the recession of more than 100m of ice, seen to the left of Ama Dablam. The dramatic melting of glaciers and ice witnessed at lower altitudes is not yet seen at higher altitudes where the temperatures are much lower. Photograph: The Mountain Institute/Erwin Schneider and Alton Byers

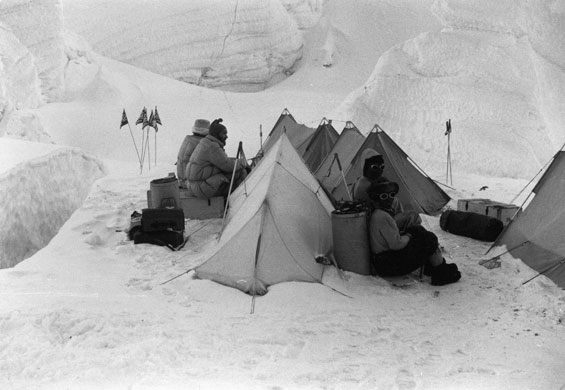

Bottom: Alton Byers's 2007 panorama shows how although glaciers all over the world are shrinking this is not the case everywhere. The contrast between the two images shows that global warming has not yet led to dramatic ice loss at extreme high altitudes (ie above 5,000m). Photograph: The Mountain Institute/Erwin Schneider and Alton Byers

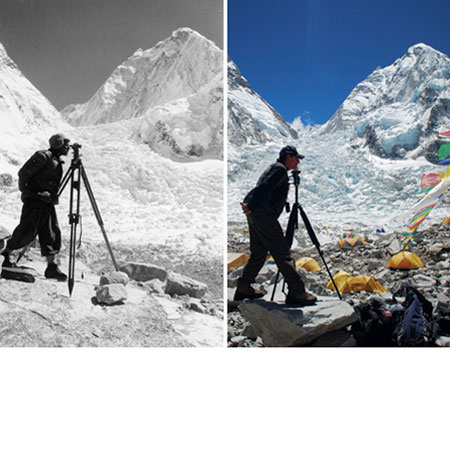

Bottom: Alton Byers had his photograph taken in the same spot almost 50 years later during his expedition. Byers is a mountain geographer and climber specialising in high altitude ecosystems. Over three decades he has worked in the remote mountainous regions of Africa, South America, Asia, and North America. Photograph: Courtesy of Jack D. Ives/The Mountain Institute/Fritz Müller and Alton Byers