Gingerly, again, to an old friend, as Gordon Taylor OBE finds himself once more in the headlines. At the time the Fifa scandal broke a couple of months ago, the players’ union boss was swiftly out of the traps.

“The game has been tainted and besmirched with corruption at the highest level by custodians who have ‘feathered their own nests’ with monies meant to be used for facilities, pitches and players all over the world,” Gordon told FIFPro’s European congress.

“The time is here to clean out the corruption and to place ourselves at the top table as guardians of the game … The time has come for players and their unions to seize the moment and bring a breath of fresh air, integrity and solid sensible leadership.”

Thanking you, Gordon.

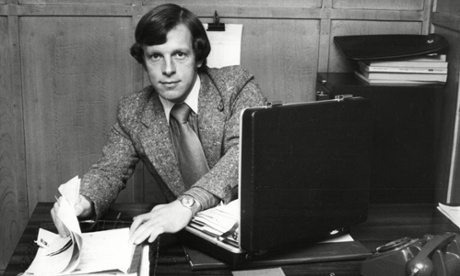

And yet, perhaps there is the need for a velvet revolution closer to home? Mr Taylor has been in his job for a mere 34 years, with his salary popularly guestimated at £1m – until a few days ago, when it was revealed he had taken home £3.4m in 2014. That being the financial year in which he was reported to have run up gambling debts of £100,000, despite having vaunted a “zero tolerance” approach to gambling by his player charges, there are those who wonder if such remuneration is entirely performance-related. As much as it ever has been, is the answer to that one.

A list of Taylor’s greatest hits is perhaps too well-worn to reprise in full, but a highlights reel would certainly include: his public discussion of private conversations with Paul Gascoigne about the latter’s mental health; a similarly idiosyncratic approach to confidentiality as far as Joey Barton was concerned; his decision to take a hush-hush £700,000 pay-off from News International for phone hacking, rather than expose a story he might reasonably have imagined would affect many of his members; and, earlier this year, his comparison of Ched Evans with the Hillsborough justice campaigners. “I have been through most things in life,” Gordon once declared – except, perhaps, extended periods of competence.

In the end, though, any discussion about the position of the PFA boss ought to be as much about the job’s possibilities as the deficiencies of the present incumbent. Taylor took the gig back in 1981. In the radically changed football landscape, I would be spellbound to see what might be achieved in all the areas of national life which football touches if players could – or cared to – avail themselves of a genuine firebrand as their union leader.

Racism, remuneration, disingenuous rows about “role models” – all of these issues could be far more meaningfully and positively debated were the players’ union helmed by someone willing and able to stand up for footballers in an era when the real powers in the sport have conveniently steered the public sentiment toward the motto “don’t hate the game, hate the playa”.

So successful is this sleight of hand that the very idea that footballers should have a union rep is many people’s idea of a joke. “Pampered”, “preening”, “prima donnas” – it’s a cue for all those tired old p-words to be given a runout, suggesting people prefer footballers as late capitalist scapegoats than to consider in whose interests it is for them to think this way. Thus preposterously disproportionate amounts of ire are directed at Raheem Sterling’s negotiating tactics, while Wayne Rooney’s salary is frequently discussed in terms of how many nurses it could provide, as though it were the responsibility of Manchester United to staff the NHS. Naturally, this is only too helpful to those whose actual responsibility it is to staff the NHS, who rush to give their view on irrelevant pieces of football news with increasingly frequency. The football story on which David Cameron cannot be persuaded to comment has yet to be found; the welfare cut on which he can remains similarly elusive.

Against this backdrop, alas, Gordon Taylor is the worst type of establishment mediocrity to hold the position he does, even if he hadn’t been in post longer than most of the world’s less cuddly dictators.

The perfect choice for his replacement would be Gary Neville, whose reputation for calling out some of the iniquities of the modern game is better founded than most. If only Neville weren’t so frequently touted as a future England manager – a job whose prestige appears to be in permanent decline. In this day and age, the PFA gig could be far more electrifying. Agents, owners, the place of football in society, the clear issues all too many around the game still have with young working class men becoming millionaires, the bizarre belief that football is supposed to mitigate the deficiencies in rape sentencing – there is so much that a smart, brave advocate could do with the job. Just imagine if the PFA were represented by someone who, say, cared to wonder more provocatively why so many of those censored by the FA for racism have been black themselves, rather than a man who – in the memorable judgment of Peter Schmeichel – is more concerned with “getting great deals on cars & other luxury goods for members”.

My own view is that football reflects society rather than the other way around, and that someone with a brain and mouth is needed to wrest popular opinion away from the real powers in the game – who, contrary to what they want you to think, are not the people on the pitch.