In our current post truth world, “Facts Not Opinions” feels like it would be a fine strapline for the many fact-checking agencies we increasingly rely upon. But it is not. Instead, the words sit carved on the 150-year-old pedimented entrance to Kirkaldy’s Testing Works in Southwark, a stone’s throw from Tate Modern.

There could not be a greater contrast in the two buildings, though each is a reminder of the area’s mighty industrial past. Tate Modern was formerly Bankside Power Station — designed by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott, who also finessed the Battersea Power Station — which opened in 1962, closed in 1981 and still looks like a cathedral of power. Kirkaldy’s Testing Works looks like a Renaissance building that wouldn’t be out of place on a Venetian canalside, but it is a temple dedicated to destruction. It opened in 1873 and is the earliest purpose-built independent commercial materials testing laboratory in the world. It still houses the main machine that it was designed for — a 14.5m leviathan that stretches the length of the building.

David Kirkaldy was a late bloomer. Born in Mayfield near Dundee in 1820, he apprenticed aged 23 at the Glasgow shipbuilding firm of Robert Napier & Sons. His talent for drawing saw him rise to become the chief draughtsman: his beautifully detailed image of Persia, the first iron-hulled vessel built for Cunard, was the first and only engineering drawing to be exhibited at the Royal Academy. During the latter part of his career with Napier he undertook tests on wrought-iron and steel specimens and designed a tensile testing machine. It was a time of huge industrial advancement, with new materials and technologies being introduced into all walks of Victorian life. Naturally, it was important to know if these worked.

Kirkaldy left the firm in 1861 to set up his own independent testing company, and at its heart was his patented Universal Testing Machine. The purpose of it was that a metal sample of iron or steel could be placed in it and tested for compression, torsion or stretch to see if it would fail. And where better to set up his new business and to employ his invention than London?

Kirkaldy’s reputation grew with an early commission to test the then-new Blackfriars Bridge. Soon his first premises at the Grove, Southwark, where he’d moved in November 1865, were too small. He turned to the architect Thomas Roger Smith to design the magnificent Italianate building to accommodate his giant machine: the leviathan was installed in its new home at 99 Southwark Street in 1873 and has remained there ever since.

Business boomed — quite literally, given one of his commissioners was the German steel magnate and arms manufacturer, Alfred Krupp, also known as The Cannon King. Kirkaldy was asked to test materials for bridges close to home, such as the Hammersmith Bridge through to those much further afield, including Eads Bridge over the mighty Mississippi in the US, then the longest arched bridge in the world. He also worked on failure: when the Tay Bridge collapsed in 1879 killing over 60 people, Kirkaldy found the source of the disaster to be the join between the wrought iron tie bars and cast-iron columns.

His son and grandson continued the family tradition, adding more famous buildings and structures that have been tested in this small corner of Southwark, including Wembley Stadium (1923), the chains supporting the Festival of Britain's Skylon (1951) and a De Havilland Comet crash (1954).

The machine could exert an extraordinary 450 tonnes of pressure – the equivalent of 62 double-decker buses stacked one on top of the other bearing down on a single smartphone screen

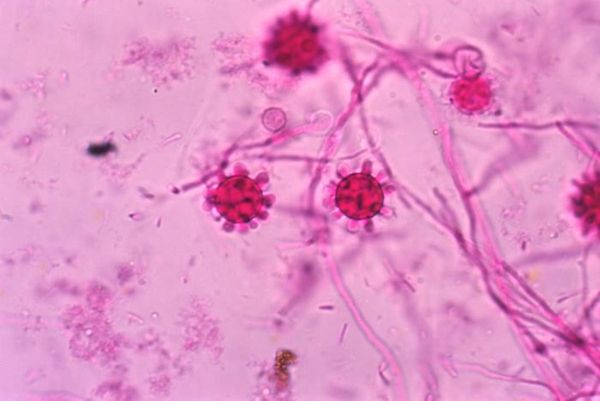

Visit and inside, visitors will be met by a temple to destruction. The star of the show is undoubtedly the 116 tonne Universal Testing Machine, originally powered by water pressure driven by a steam engine. The machine could exert an extraordinary 450 tonnes of pressure – the equivalent of 62 double-decker buses stacked one on top of the other bearing down on a single smartphone screen. But this is not the only machine: the building is filled with devices that will crush, stretch, batter, shatter, dent or twist whatever is placed in their maws.

There is a Denison chain tester for marine anchor chains, Brinell and Vickers hardness testers, and countless others that were used to test a huge variety of materials from the strength of rope, wire and bolts to the quality of cement, parcel tape or parachute lines. On the upper floors of the building, Kirkaldy created his own Museum of Fractures – essentially an exhibition of specimens that had failed the rigorous tests, which served both as a teaching tool and a clever marketing device to alert new clients of the importance of testing. Unfortunately, this museum within a museum no longer survives, mostly destroyed by bomb damage during the Second World War.

The business finally closed in 1974 but by then the building was considered nationally important and had been listed. Ten years after the doors closed, that protection was upgraded, specifically because of the extraordinary machinery that remains in place and intact inside. At the same time, it was established as the Kirkaldy Testing Museum, a fascinating volunteer-led experience which opens to the public for taster days, group tours and school visits.

Most modern museums have now moved away from an old-fashioned approach that demanded ‘Please do not touch’. But the Kirkaldy Testing Museum takes this to a whole different level where its main message to visitors is ‘We want you to break something.’ All in all, a smashing visit.

99 Southwark Street, SE1, testingworks.org.uk

John Darlington is Director of Projects for World Monuments Fund, July 2025