Hell is Us proved a huge surprise to me this year, as I did not know what to expect when first getting into the game.

Encountering everything that I did about the state of Hadea, the game's fictional nation and setting, which is embroiled in a brutal civil war unfolding in the background, I had to learn more about it.

Speaking with creative director Jonathan Jacques-Belletete, I learned about how Hadea came to be, why it was made, and how central a role it plays within Hell is Us, to the point of it being more or less the actual main character aside from the protagonist, Remi.

The director also touched on topics of war, how Hell is Us tackles the idea of it, and how civil wars and events like those transpiring in Hadea differ from professional armies following rules of engagement.

Here is the full interview.

Note: Parts of this conversation were edited or condensed for better text clarity.

In action-adventure puzzle games like Hell is Us, Tomb Raider, Indiana Jones, and others, the backdrop isn't so detailed. They usually just make a setting, while the personal quest of the protagonist is the most important part.

Why did Rogue Factor decide to make such a robust world that's unfolding behind the scenes, away from the personal story of the protagonist, knowing the player won't directly experience it?

Jonathan Jacques-Belletete (Creative director, art director, Rogue Factor): I think there are multiple levels to why we did it this way. One of the reasons might be a bit unconscious, in the sense that I am first and foremost a world builder. This is one of my main skills, and I really enjoy stories that are about the world in which they take place.

Those stories still need to have characters, but I don't get particularly annoyed or upset if the focus seems to be more on what's happening around the main character, or at least on an equal level. So that's a bit kind of like my personal thing.

The second variable I would say is we wanted all the details and all the kinds of psychological aspects of it. I think because of that, by default, it created an extremely present world building that was really on the front row, on the main stage if you want.

And like you said, we wanted Remi, the hero, to be able to interact with it, but we didn't want him to be able to solve it. I don't think it's possible that one human being solves a civil war or any war. It only happens in Hollywood movies or in video games, but not in this video game. Even the UN peacekeepers have never managed to pull that off.

All these things put together led to having this extremely potent, extremely forefront-ish world-building that really became the main character.

When building Hadea's, kings, history, isolationist culture, ethnic groups, character of the nation itself, did Rogue Factor look into real-life nations and cultures to make their in-game counterparts more realistic or feel less fictional?

Jacques-Belletete: Of course we did. To begin with, in terms of [accurately portraying] the civil war, we didn't look just at one situation. We looked at many [wars], like the Rwandan genocide, and obviously the Bosnian War, Sierra Leone, and much, much more. But of course, we took a bit in terms of situations, contexts, what lit the flame, all that.

We took a bit from all of these at the same time. And politically speaking, we also took a little bit left and right as well to build Hadea, to build its background.

Because one thing that you start noticing when you really deep dive into these types of conflicts is that they have a lot of things in common, right? Like the distortion of the past or the weaponization of long past events; like mythical figures or historical figures that nobody cares [about] anymore, [that are] suddenly brought [to the forefront].

You see it in Britain right now with the St. George's Cross. And I'm not making a statement about that at all. I'm not at all saying if I agree or disagree, but I had never heard of that person before. And I really wouldn't be surprised, again, not a criticism, if some people who are now waving that flag didn't even know who that person was three months ago.

[There is also] almost the invention of differences between group A and group B. Sometimes they're exactly the same people. They speak the exact same language. And in order to appear more different, to justify the atrocities and the violence, they will invent or shine even more light on things that have never bothered anyone before. So these tend to be a bit more, less present in certain conflicts and more in others. But they're very, very often there.

So it's really just an amalgamation of all these things that seem to always be present, [such as] obviously nationalism and so many other things, and it created Hadea. And visually speaking, for me, it was a big mix between, yes, Eastern Europe and Southern Europe, but also the English countryside, kind of the mossiness and the greenness of the British countryside. But, yeah, it's very much taken from so many sources where these types of conflicts have happened.

In what capacity did the Yugoslav Wars, and specifically the Bosnian War, since it was the one where religious differences caused the divide, like with the Sabinians and the Palomists [in Hell is Us]?

Jacques-Belletete: Obviously, we 100 percent looked at what happened in Yugoslavia, and the situation between the Serbs, the Croats, and the Bosniaks was 100 percent our inspiration. But there's also a big reference to the Reformation of the Christian Church, back when Protestantism came in and all that stuff. So, like I said, these things are quite common.

[We looked at] the hundreds of years of religious war in Europe between when Luther did his thesis and all that stuff. It's also a huge inspiration. But yes, absolutely, what happened in Yugoslavia, sadly, religiously speaking, where the lines were drawn, was an inspiration as well, for sure.

But it was not the only one.

Hell is Us combines a lot of elements of various genres, so from Souls combat to Metroidvania levels, action-adventure, and puzzle-solving. The themes, though, transcend arcade. They are way beyond video games as a mode of entertainment, especially in their meditations on war, famine, and the effects of contemporary conflicts and how devastating they can be.

So would you describe your game as an anti-war title? And what is your goal in creating such a game alongside the puzzles, history, archaeology, and other aspects?

Jacques-Belletete: It's definitely an anti-war game, but it's even more of an anti-human violence game. [But it's not about] states waging war, one state against another state, with what we call professional armies, and warfare for resources, and stuff like that. I think there are a lot of games [about that], like for example Spec Ops: The Line. It's very much anti-war, and what an amazing game for it.

Hell is Us is kind of automatically anti-war, but we chose civil war because it's a lot more anti-human violence, human barbarity, because it's not about professional soldiers that are paid to do something. Atrocities happen in any war, like country against country; like Americans have done [in the Middle East], professional soldiers have done horrible, atrocious acts. Same with Canadians, something that happened with our 101st Airborne Regiment back in the 90s, they disbanded it because it was absolutely insane.

But technically, as weird as it sounds, there are rules, and there are certain things that nations at war are supposed to do and not do. But when it's people, regular people like you and me, that get to a point where they decide to take out their machetes and whatever weapons they can put their hands on, it's just absolute pure madness, you know what I mean?

It's just absolute insanity that happens, and that's the human barbarity. We tend to think that barbarity was something that happened an extremely long time ago, but it's inside all of us, it's inside me, it's inside you, it's inside everyone. Under the right circumstances, it can all come out.

That's what the game is about, that's what the game is anti, much more than just anti-war, if you can see what I mean.

“We could have gone so much further.”

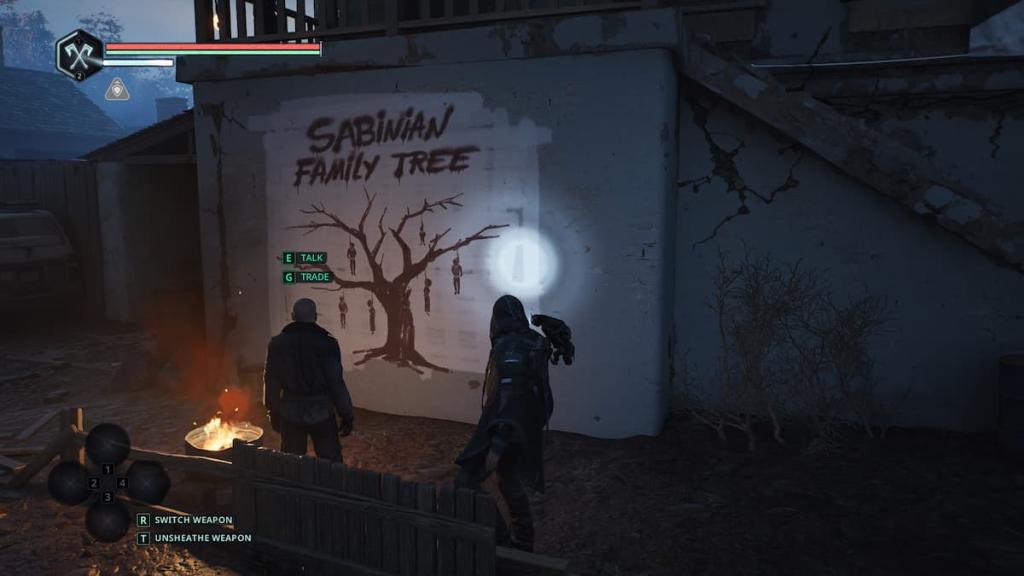

Jacques-Belletete: But for example, that graffiti of the hanging tree, and also the hanging tree in the map, that's a very good example. Again, technically, [in] state wars, you shouldn't see things like that. They happen, I'm sure they do. But let's say when the United States and all its allies invaded Iraq after 9/11, I'd be very surprised if there was a tree where American soldiers hung civilians.

But seeing things like this in a civil war, a hanging tree or something of that magnitude, is not uncommon at all. That's where the madness is. So, that's the statement of the game.

And that's why all the emotions, the themes of emotions and passions and all those things come into play in the game, because when you do these things to other people, and sometimes even people that you used to know or know of, it's pure emotions. You know what I mean? It's not mechanical. And that's very much what the game is about.

I've read certain things lately where people say, like on Reddit and whatever, that we pushed it a lot. They're definitely right. But we could have gone so much further. We actually restrained ourselves. And also, there's no gore in the game. It's all about how atrocious a little scenario is.

It's not about gore. It's not about blood. It's just about, holy f**k, what just happened here? And we could have gone much worse. What happens in real life is much worse than what's in the game.

On that point, since you could have gone a lot further, given how detailed this world is, it would be a shame not to see more of it, to experience more of it, maybe even more personally, more up close. So, does the studio plan, or is it talking about perhaps doing more with Hadea, exploring that side of the world, instead of the puzzles, the deep underground kingdoms, lost prophecies, and so on?

Jacques-Belletete: The vibe that we've created with Hell is Us, and the gameplay philosophies and all that, are very much now a Rogue Factor thing, and we're absolutely continuing in that direction. No matter what game we would make, there's a style we want to keep moving forward. Now, if we were ever to go back to the world of Hell is Us, or Hadea, there is so much stuff.

Tomorrow, I could send a synopsis to writers to start novels about the past. Or, as you played, if you paid attention to the details, the Limbic Invasion in the game is the sixth one; there were five before.

Pick any one of the five, and we could have a whole game, or a whole movie, or a whole novel with just that one. We have the people who took part in, let's say, the Second Limbic Invasion; we have their names, and who was the king at that point, who did what, how did the invasion happen, how was it quelled, etc.

And then in terms of contemporary Hadea, there's so much. Now, I don't think, because that's the second layer of your question, if I would make something that's just about Hadea without its past, and all the cosmic horror vibe, [because] I don't think you can separate the two.

I don't think we could make, I mean, technically we could, but I don't think we'd [want to] make like a TV show of just a little village in northern Hadea, with their day-to-day lives, you know what I mean? Do we have information for that? Of course. But Hadea, Hell is Us, is about everything that we've created. Its past, how it's intertwined with its present, and the Limbic Invasions, and all that.

But there's still so much to say, so much to show, and I think we could ride that wave for quite some time.

I know it's probably ambiguous on purpose, but where exactly would Hadea be? I know the game takes place in an alternate version of our world. I saw the UN flag, which had the map of the world. I was actually not expecting the game to be set in our world, so where would you place it geographically?

Jacques-Belletete: Mathieu and I, the lead writer, wrote the game together, the world-building, and then the game itself. We wrote it together, and I don't recall, honestly, in all the years, in all the thousands of hours we spent together creating that story and that world, that we said, Where is that country exactly? It was not important.

What was important was to convey that it's definitely on Earth, right? We can say an alternative reality if you want, because that country actually doesn't exist in this reality, but we didn't even see it as an alternate reality; we just saw it as this world, and it's somewhere in this world.

Now, [about] the ON, we didn't call it the ON to boast a concept of an inverted or alternate reality. I would have liked to call them the UN. We actually contacted the United Nations, and they didn't allow us to use their name; I had to change it. They allowed us to use their baby blue color for their helmet and their flak jacket, even their Pantone code, [and] we were fine with that. We could use the white vehicles with the black stencils on them, but the actual name and the logo, we had to modify.

So that's the only reason it was portrayed as a parallel universe. I had no choice, because if I had had my way, it would have been the UN, the United Nations, and that's it, right? But we couldn't.

One of the reasons I think Mathieu and I never bothered [with geographically locating Hadea], is what's happening inside the country is so atrocious, that if we would have pinpointed in the slightest, at one part of the world, a little more than another, or one people a little more than another, or anything else, we would have gotten into trouble.

So you might feel influences, you might feel philosophical influences, historical influences, natural influences, but at the end of the day, it's all they are, and if you really dissect them, they're from all over the place.

Going back to when we first started this conversation, you said, first and foremost, that you were a world builder crafting histories, whole timelines of events, and so on. What advice would you give to other world builders, designers, or writers trying to create entire worlds, or even one nation, with the history as rich as Hadea's?

Jacques-Belletete: That's an amazing question, and nobody's ever asked me that. That's actually hard to answer, because I think it's something that comes very naturally to me. I'm not sure if I have a specific method or something like that.

It's going to be bizarre what my answer is going to be, because they're not tools that I use, because like I said, it's just the way that my brain works naturally. But my answer is that so many tools exist nowadays that can help you with world-building, like amazing decks of cards that you can buy that help you.

Even though I said it kind of comes naturally to me, I'm an avid reader. The minute a subject interests me, I go on Amazon and even if I'm like, oh, I might use it or not, I'll order 10 books on it, and next day they arrive and I just start reading.

So read, read, read, read, read, read, read, read, is what I would say. Whether it's a theme, a trope, a context or a real history, it doesn't matter. Whatever interests you for your world building, find the best books on it and go read and read and read and read. Always have a notebook with you. Constantly take notes, whatever idea you have. And just tinker, just tinker, just nonstop.

I use Miro and I love it. My brain is very chaotic, and Miro for me is very freeform, free flow. There are no rules on how you want to place your things. I find it very good to put your ideas down.

One of the things that I like the most when I build worlds is creating names, inventing names. I can spend hours just on one name. There's always a meaning in the names, and I take different names. I combine them.

If you look at the map in Hadea in the APC, and you zoom in when you choose what level you want to go to, there's a whole world-building part you [probably] haven't seen, because I've created hundreds and hundreds of towns and cities.

The names of the highways and the names of the regions and everything. That took me months and months because finding the right name for each little village, each little town, they all mean something.

Like our content? Set Destructoid as a Preferred Source on Google in just one step to ensure you see us more frequently in your Google searches!

The post Hell is Us creative director opens up about who the ‘real main character’ is appeared first on Destructoid.