One year into U.S. President Donald Trump’s second term, questions about his health and competence are as pervasive as the gilt sprawling through the Oval Office.

These questions grew even louder following his rambling speech this week at Davos, where he repeatedly referred to Greenland as Iceland, falsely claimed the United States gave the island back to Denmark during the Second World War and boasted that only recently, NATO leaders had been lauding his leadership (“They called me ‘daddy,’ right?”).

Read more: Trump's annexation of Greenland seemed imminent. Now it's on much shakier ground

Do swollen ankles and whopping hand bruises signal other serious problems? Do other Davos-like distortions and ramblings — plus a tendency to fall asleep during meetings — reveal mental decline even more startling than Joe Biden’s in the final couple of years of his presidency?

This is not the first time in White House history that American citizens have had concerns about the health of their president — nor the first time that historians like me have raised questions.

The experiences of Trump’s predecessors remind us of the dangers inherent in the inevitable human frailty of the very powerful.

Presidents with physical health issues

Frailty can entail crises in physical health like William Henry Harrison’s 1841 death from pneumonia 32 days after his inauguration or Warren G. Harding’s heart attack and death in 1923.

Frailty can also involve weaknesses in brain function, which impact the capacity for analysis and problem-solving.

Bodily trauma can have obvious effects on presidential competence. Sometimes it’s a temporary impact, as with Dwight D. Eisenhower’s 1955 heart attack and recovery. But sometimes it’s permanent: Woodrow Wilson never recovered his capacities after an October 1919 stroke, with White House leadership languishing for 18 months under his wife’s gatekeeping until his death.

In other cases, the effect of physical ailments on competence was less clear — and therefore debatable. Franklin D. Roosevelt’s heart problems during the Second World War grew serious enough to contribute to his April 1945 death. Did they also compromise his mental capacities during the controversial Yalta Conference?

Did John F. Kennedy’s undisclosed Addison’s disease and medication regimes affect his ability to navigate major challenges like the Cuban Missile Crisis or Vietnam?

Mental health concerns

There have also been debates about the possible competence consequences of the behavioural tendencies and mental health conditions of several American presidents:

• Did Abraham Lincoln’s bouts of deep depression affect leadership capacities during multiple Civil War crises, including the Union defeat at Chancellorsville in May 1863 or during cabinet conflicts?

• Did Theodore Roosevelt’s impulsivity help shape what even his secretary of state once privately called the “rape” of Colombia in order to build the Panama Canal? (Harvard psychologist and philosopher William James said Roosevelt was “still mentally in the Sturm und Drang period of early adolescence”).

• Did Richard Nixon’s periodically high stress levels and alcohol consumption influence his decision-making on the Cambodian incursion of 1970 or the Watergate crisis?

Questions and concerns about Trump’s physical and mental health, then, aren’t unique — even if the causes for concern are far more numerous than they were for previous presidents.

The impact of physical health on competence seems the less urgent of worrisome issues. While the Trump presidency as a whole has been notoriously prone to dishonesty, exaggeration and avoidance, the current medical team seems to be offering reasonable transparency.

Tests have been identified — for example, an October 2025 CT scan to assess potential heart issues — and relatively non-alarming diagnoses have been offered (“perfectly normal” CT scan results; common “chronic venous insufficiency” is responsible for swollen ankles).

More troubling is Trump’s mental health — both his full cognitive capacities and his psychological profile.

Cognitive issues?

In 2018 and 2025, Trump was given the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) a screening tool for possible dementia. Despite the president’s claim to having “aced” the test, his score has not been revealed.

Numbers matter here. Out of a maximum 30 points, scores below 25 suggest mild to severe cognitive issues.

Of equal importance, the MoCA provides no insight into markers of mental competence, like reasoning and problem-solving. Well-established test batteries cover such ground (the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale is widely used), but Trump has not likely worked through any. (Neither, to be sure, have any predecessors — though none have raised the concerns so evident in 2026.)

Unofficial diagnoses of personality characteristics also fuel debate about Trump’s competence and mental health. The scale of the president’s ego is a prime example of concern.

Psychological issues?

On one hand, in the absence of intensive in-person assessment, psychiatrists are understandably reluctant to apply the label of “narcissistic personality disorder” (NPD) as defined by the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). On the other hand, many observers are also understandably struck by how Trump’s behaviour matches the DSM’s checklist of symptoms for the disorder.

The president clearly displays the grandiose sense of self-importance seen as a primary marker. Trump’s “I alone” and “I could shoot someone on Fifth Avenue” boasts of earlier years have grown exponentially by 2025-26. He’s depicted himself as pope or “King Trump” bombing protesters.

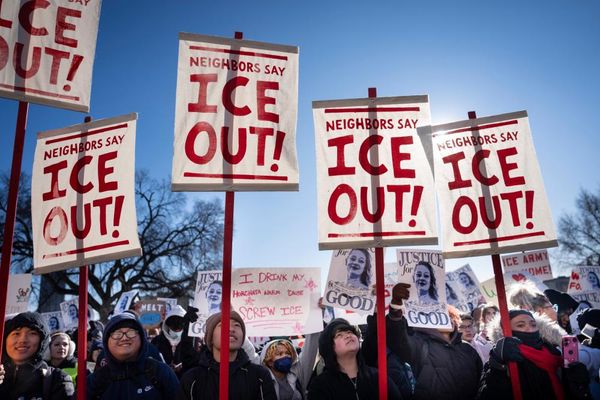

More serious are his endless and false claims that he won the 2020 presidential election, that he has the right to torch constitutional norms like “due process” that are enabling ICE abuses in Minneapolis and elsewhere, and that he can disregard the need for congressional approval on policies like reducing cancer research and other health programs.

Trump’s declaration that only “my morality” will determine his defiance of international laws and standards (as in threats to Greenland and Canada and his actual invasion of Venezuela) are also deeply troubling, especially given serious questions about that morality in terms of the Jeffrey Epstein files.

Psychiatrists also associate NPD with a sense of open-ended entitlement. Comic examples emerge: rebranding the (now) “Donald J. Trump and John F. Kennedy Center,” his lack of embarrassment in relishing the absurd FIFA Peace Prize or María Corina Machado’s surrender of her Nobel Peace Prize.

Brazenness

Trump’s willingness to trample upon rights within the U.S. and his apparent eagerness to disrupt and dismantle the building blocks of the post-Second World War international order are also possible signs of psychological problems.

Read more: Venezuela attack, Greenland threats and Gaza assault mark the collapse of international legal order

He is equally brazen in fostering the wealth of his family and friends: for example, accepting emoluments like multi-million dollar donations for a White House ballroom that will surely be given Trump branding (to compete with the Lincoln Bedroom?) and using Oval Office prestige to turbo-charge massive real estate and financial ventures.

The Trump family’s World Liberty Financial cryptocurrency enterprise “earned” more than $1 billion in 2025, after all.

Against the backdrop of the looming mid-term elections, Trump’s ever-compounding ego and appetites remain of burning concern — along with his overall physical health and mental competence. Other presidents faced similar questions even without the current storm of scandals and extremes.

Will Trump relish the distinction of leaving his predecessors in the dust on this front too?

In the past, Ronald W. Pruessen has received funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.