Thursday, June 5, 1975. Following an overwhelming vote in favour at the referendum, Prime Minister Harold Wilson takes Britain into the European Economic Community, aka the Common Market. Goodbye fish and chips, hello frogs’ legs, warns one especially ‘patriotic’ tabloid. But by the end of the month, there is an undeniable feeling of joie de vivre in the air as the country plunges into one of those “Do you remember…” heatwaves that inspires TV newsreels of heat-stroked housewives frying eggs on pavements. Bottled water hasn’t been invented yet, so everyone chain-sucks ice lollies.

The UK singles chart is not so sun-dappled: Tammy Wynette’s Stand By Your Man spends four weeks at No.1, and is followed into the top spot by Whispering Grass by two of the stars of BBC TV comedy It Ain’t Half Hot Mum (delightful then, ‘cancelled’ now). Rod Stewart’s Sailing will stink out the rest of the summer hols.

Album-wise, it’s equally dispiriting. Among the year’s biggest sellers are Perry Como’s 40 Greatest Hits, The Best Of The Stylistics, and 40 Golden Greats by Jim Reeves. Although Floyd, Zep and Queen release landmark albums in ’75, they can only muster one greatest hit between them: the six-minute mock opera Bohemian Rhapsody.

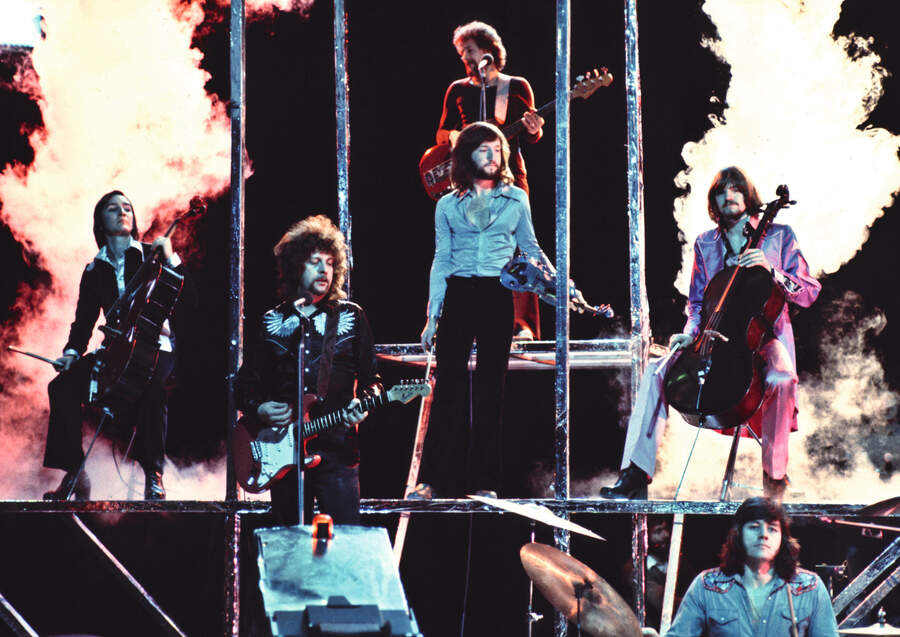

Kids – you wanna know how punk rock started, back in ’76? Pass the amphetamine sulphate. Or, alternatively, grab some busty cellos and livewire violins and uncork a decent red. Add some big booming drums, some loud electric guitars – and kaboom! Beethoven-meets-Chuck Berry! Mozart on the Moog! Forget parochial UK punk for bored teenagers, this was pan-European sophistipop for all the family.

Wait… why are you looking at me funny?

It was the fourth ELO album Eldorado that singer, songwriter, guitarist and producer Jeff Lynne, considered the turning point. “That was the first time I’d used the [full] orchestra and choir,” he told the LA Times in 1977. “It was a giant step, really, and from then on I’ve seen what direction to go in.”

That Eldorado is now regarded in both Classic Rock and Rolling Stone as one of the Top 50 Greatest prog albums of all time bestows a retrospective critical glow ELO never achieved in their heyday. That Eldorado became their big commercial breakthrough in the US, a Top 20 record complete with Top 10 single, Can’t Get It Out Of My Head, was proof enough for Lynne that ELO were both the real deal and that they now truly belonged to him.

Recording the next all-important ELO album, at Musicland, a studio in the basement of a hotel on the outskirts of Munich, in June 1975, Lynne was now determined to shed the overt prog associations in favour of more melodically memorable songs, compact verses blossoming into full-spectrum choruses. In short, catchy chart hits. Or, as ELO’s fearsome mafia-connected manager Don Arden used to counsel: “Art for art’s sake, boys. Hit singles for fuck’s sake”.

The fifth ELO album, to be titled Face The Music, would initially be presented as another conceptual masterwork, as had all their albums up until now. But, just as Arden predicted, it would be the first really big ELO single, Evil Woman, that would be the real difference maker, becoming their first single to go Top 10 in both the US and UK. The last track recorded for Face The Music, Evil Woman was an afterthought dashed off in minutes by a panicked Lynne after realising “there was not a good single” on it. “So I sent the band out to a game of football and made up Evil Woman on the spot. It was the quickest thing I’d ever done.”

It was also one of the finest. This was no longer about gimmicky classical rock. “I don’t think that’s us any more,” Lynne insisted. In fact, Evil Woman was the permissive sound of 1975 finessed Phil Spector-style into one glorious crescendo of gospel blues piano, funky jingle-jangle guitar, disco-cooking clavinet, Queen-lush harmonies, heavenly strings, even a subtle Beatles hat-tip in the lyric ‘There’s a hole in my head where the rain comes in’, in reference to Fixing A Hole from Sgt. Pepper’s.

“It was kind of a posh one for me,” said Lynne, “with all the big piano solos and the string arrangement. It was inspired by a certain woman, but I can’t say who. She’s appeared a few times in my songs.”

Even without Evil Woman, the rest of Face The Music would probably have been judged a more-than-worthy successor to Eldorado, from its stormy instrumental opener Fire In The Sky – big-valley production, noises-off knocking, back-masked spoken words, an angelic choir summoning the spirit of Handel’s Messiah, joined by melodramatic drums, kick-ass guitars and swirling synthesisers – to its mellifluous grand finale One Summer Dream. It also contained another hit single – at least in the US – in Strange Magic, a wistful swirl of honeyed guitars and synth-silk vocals Lynne would eventually re-record several times over the years. There was also an all-out rocker in Poker.

Lynne had largely abandoned the sound-ofthunder guitars he’d showcased on earlier ELO recordings, even leaving the vocals on Poker to bassist Kelly Groucutt, propelled by the galloping synths of Richard Tandy.

Tandy was now Lynne’s right-hand man in the studio. “He’d argue with me, hang out till six in the morning, he’d do whatever was needed,” said a grateful Lynne. Tandy, a multi-instrumentalist from the same hardscrabble Birmingham scene as Lynne, now oversaw a dazzling array of pianos, Moog, clavinet, Oberheim synth, Wurlitzer electric piano, Mellotron, Yamaha analogue synth, Arp 2600 synth, and harmonium.

As importantly, Tandy also served as Lynne’s musical envoy to Louis Clark, who’d conducted the 40-piece orchestra and choir on Eldorado and now returned to do the same on Face The Music. (Clark later became the evil genius behind Hooked On Classics.)

Bev Bevan would slap down the drums in Musicland’s echoey service corridors then double-track the snare and toms. The band – completed by Mik Kaminski on violin and Hugh McDowell and Melvyn Gale on cellos – would record their parts, then orchestra and choir were added later in London. Lynne would wait until the very last minute to record his vocals. “This is what I’ve always worked for,” he said. “It’s my group, really, mine and Bev’s.” There was never any doubt about who was in control, though.

Early on, Lynne argued that the entire musical character of ELO could be traced directly back to I Am the Walrus, throwaway B-side to The Beatles' 1967 No.1 Hello, Goodbye.

He was ridiculed, of course. Comparing any group to The Beatles was simply unthinkable, let alone to do it with a group as patently uncool as ELO. Then at the end of 1975 as Evil Woman took over every radio station in New York, John Lennon, who now lived there, spoke publicly of his admiration for ELO, describing them as the “sons of The Beatles”.

After years of struggle – from schizophrenic origins to playing musical chairs with record labels, band members, management, popularity itself – ELO had finally found a winning formula. As a result, Face The Music became the template for the trio of globe-straddling ELO albums that followed: A New World Record (1976), Out Of The Blue (1977) and Discovery (1979).

Just as Don Arden predicted, however, it was a giant hit single that really made Lynne’s dreams come true. From Evil Woman would later come Livin’ Thing, Telephone Line, Don’t Bring Me Down, Mr. Blue Sky and others, all era-defining hits that by the end of the seventies had sold more than 50 million copies – allowing Arden to buy American multimillionaire Howard Hughes’s Bel Air mansion. “For cash!” as he was quick to remind you.

Born in a rundown suburb of Birmingham, this was 27-year-old Jeff Lynne in a place – musically, at least – that felt like home. Far from being a classical music revivalist, or rock avantgardist, Lynne had been brought up on Elvis, schooled by the Everly Brothers, and further educated by The Beatles.

He’d strummed the Brum scene, graduating at 18 when he joined local bigshots The Nightriders, taking the spot earlier occupied by another talented local teen, Roy Wood. Wood was off to The Move, where he would write and sing all 10 of the monster hits they set fire to the UK charts with between 1967 and 1972: Flowers In The Rain, Fire Brigade, Blackberry Way… The Move were the Brummie Beatles.

When The Nightriders petered out, Wood helped Lynne put together The Idle Race, a typical-for-the-times outfit that had also inhaled The Beatles and today sound like a very early ELO. Two albums, various singles – all written, sung and produced by Lynne – but no hits. Lynne and Wood, the latter older by a year, regularly met for a pint where the notion of “a group with strings" became a recurring conversation piece. Rock repurposing classical motifs had been on the rise since The Beatles first showed how it could be done with Eleanor Rigby and its double string quartet arrangement.

Procol Harem’s A Whiter Shade Of Pale, the biggest-selling single of 1967, was based on its incense-and-hash Hammond Organ reimagining of JS Bach’s 18th-century opus Air On The G String. Another Birmingham group shedding sixties pop in favour of seventies rock were The Moody Blues, who utilised the London Festival Orchestra for their foundational prog album from the same year, Days Of Future Past.

Wood and Lynne had an idea, along similar lines. What they both desired most, however, was to be regarded with all the gravitas that The Move had been denied. The year before, Rolling Stone had declared: “The Move deserve to be put in the same category as Led Zeppelin and the Faces.” But The Move never had a chart album, and by 1970 were viewed in the same cheerful aspect as Mungo Jerry or Slade – good for a laugh on Top Of The Pops.

They needed to alter the public mindset, beginning with their new Monty Python-esq, eight-syllable name: The Electric Light Orchestra – Wood’s idea after buying a cheap Chinese cello. Lynne rolled with it.

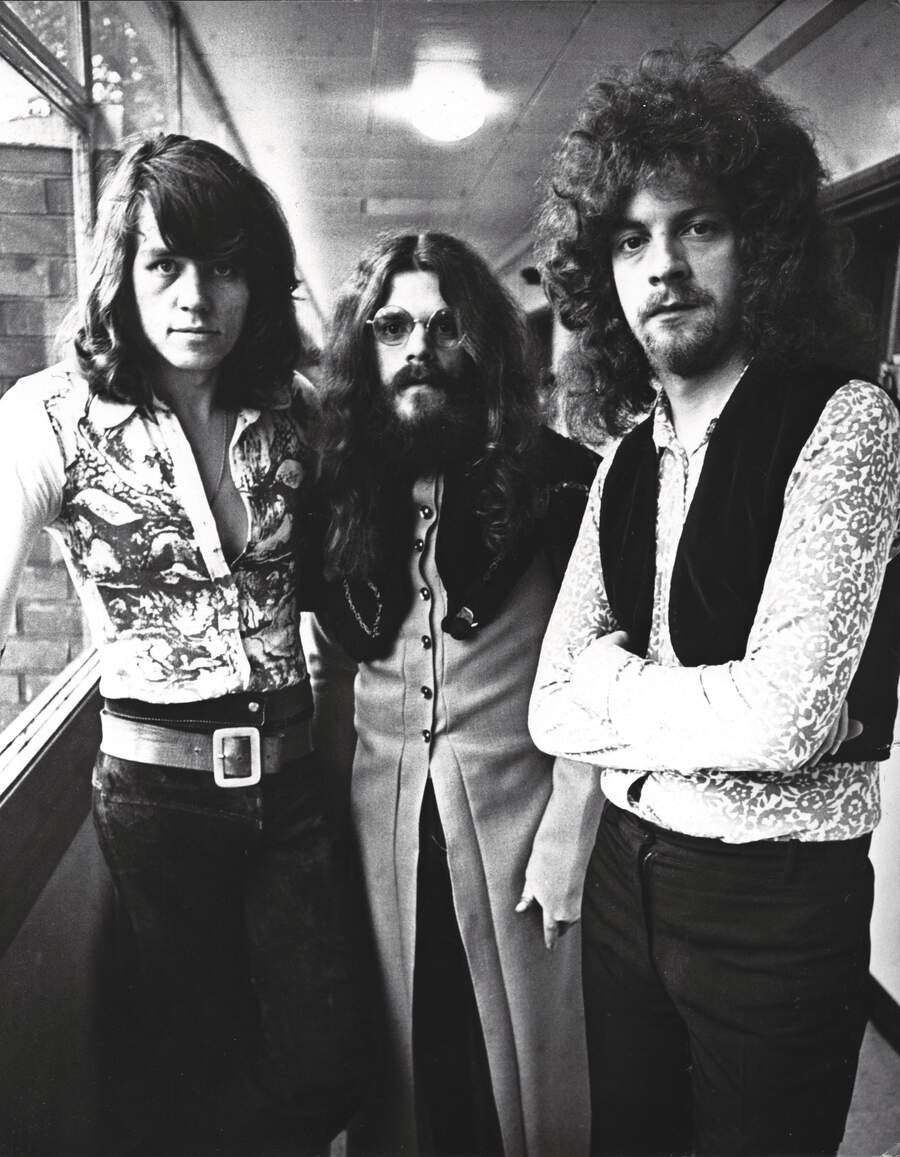

For the next year Wood, Lynne and Move drummer Bev Bevan would record both as The Move and the Electric Light Orchestra, the former to help fund the launch of the latter. The last Move album was recorded quickly, but the first ELO album, recorded at the same time, took forever as Lynne and Wood battled each other for creative supremacy. “I wanted to be boss and he wanted to be boss,” Lynne told Melody Maker.

Their debut album, No Answer, was released to little fanfare in December 1971. Four months later came The Move’s final Top 10 single, California Man – greasy 1950s-rock’n’roll-meets-pastiche 1970s-glam. Then in June came the first ELO single: 10538 Overture, a Lynne song, which he co-produced and shared lead vocals on with Wood. Bruising Strawberry Fields Forever cellos, French horns and Hendrix. It went Top 10 and No Answer finally sniffed the Top 30. The next time would be even better.

But ELO 2, in 1973, was worse. With Wood gone, Lynne overcompensated for the loss with five longer and longer tracks. The only respite was a cover of Roll Over Beethoven, with its never-getsold novelty intro. It rewarded the band with another Top 10 single, but again the album only brushed the Top 30.

The third ELO album, On The Third Day (geddit?), was closer to the orchestral pop of ELO to come, but musically unfocused; Stones rock on the minor UK chart single Ma-Ma-Ma Belle, sleek Marvin Gaye funk on Showdown. OTTD was the first of three consecutive ELO albums to not even register on the UK chart.

It was different in America, though, as each new ELO album sold a little more than the last one. With America still in mourning for The Beatles, ‘serious’ fans now turned to the new ‘progressive rock’ of Yes and Jethro Tull, Pink Floyd and Led Zeppelin. It was to this American audience that ELO was first pitched. ELO mixed classical with rock and produced extra-long album tracks that were perfect num-num for stoned FM radio listeners nursing their bongs. Hence the beating heart of the success of Eldorado.

Face The Music, released in the US in September 1975 – but delayed for another two months in Britain before it made an appearance – would further that proudly pretentious lineage. But as Jeff Lynne later confessed, on those earlier ELO albums “I was trying to write stuff that wasn’t me. It was a lot of waffle, based on instrumental, avant-garde stuff that I didn’t particularly like, but thought I should like.”

In America, where critics still judged ELO on their concepts more than their choruses, Circus described Side Two of FTM as “Lynne’s masterpiece”, and noted “influences as divergent as George and Ira Gershwin and country music…”

But side-long masterpieces were no longer Lynne’s chief turn-on. There were moments, he said, singing something for the first time, “where I’ve thought: ‘Phew, that feels like a big hit.’ It doesn’t happen often, but it’s great when it does”.

Yet despite their ever-mounting success, ELO remained faceless. Lynne riding into the British press launch of Face The Music on an elephant was cringe-inducing attempt to rectify this. As was the jarring image of an electric chair on the album sleeve.

As Bev Bevan told one reporter: “I get a lot of drugs handed to me from fans, although I never take them. I pass them onto the road crew who will scramble to get their hands on the pills and smokes. And it’s the same with girls. Each member of the band does the same with their own roadies. Few of the road crew are too fussy, especially as the night wears on and the drink takes effect.”

Lynne always claimed Newcastle Brown Ale as his narcotic of choice. “I had tried pot but it never did anything for me. I was always just a beer drinker at that time. Loads of it, mind you. I got to be enormous at one point.”

“They were like old men,” Sharon Osbourne, née Arden, told me. Tour managing the band for her father, in the late seventies, she said, “was so boring it nearly drove me mad”.

However, the demands of US tours that saw them perform 68 shows in 75 days at one point did take their toll, eventually leading to the end of Lynne’s marriage to Rosemary Adams. Two more marriages and half a century later, still no one knows what Jeff Lynne actually looks like, just the meme-like image of unruly head-and-chin hair, tinted grandad glasses submerged somewhere within.

The music really was the thing. As Axl Rose, who tried and failed to get him to produce November Rain for Guns N’ Roses in 1990, told me. “Jeff Lynne was badass. There was nothing like ELO in America in the seventies. There still isn’t.”

By 1978, ELO’s US success had been duplicated the world over, and the band that could barely fill Birmingham Town Hall when Face The Music was released now headlined eight nights at Wembley’s Empire Pool (now Wembley Arena), filling it with spaceships, robots, lasers and thousands of lit faces.

“Probably the happiest I could ever be was having the headphones on doing the lead vocal,” Lynne once said. “I loved recording all the harmonies and then hearing them come in just right when I’m doing the choruses and thinking: ‘Yes! It fits!’”