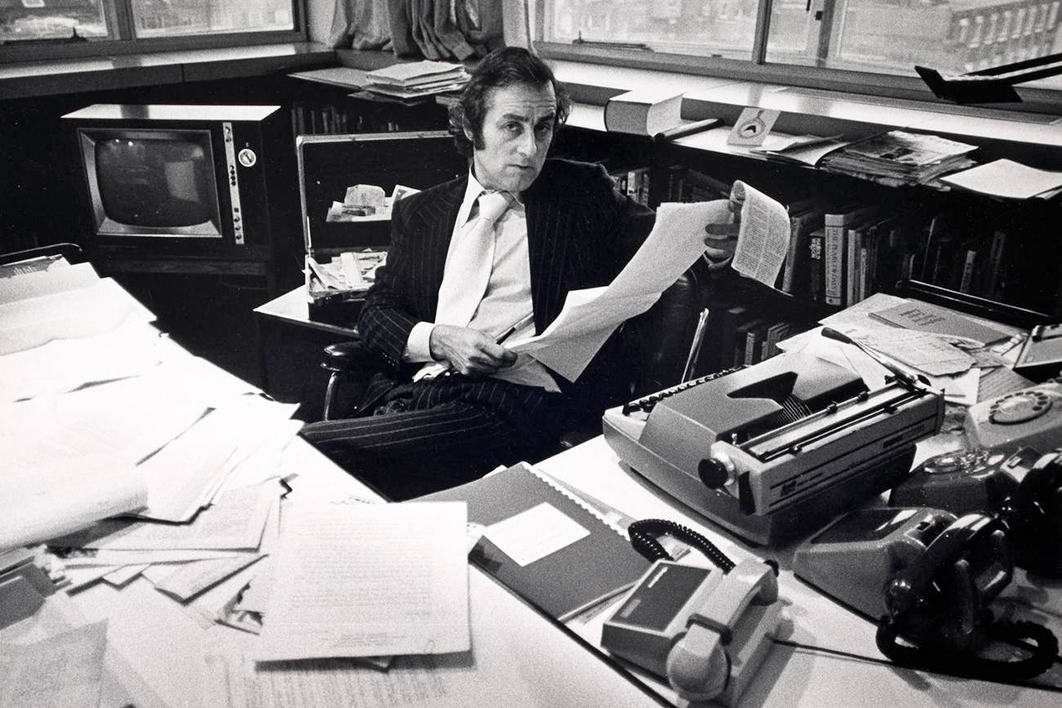

Harold Evans, who died in New York on 23 September 2020 aged ninety-two, was the most esteemed British newspaper editor of the later twentieth century. Justly so, given his rare portfolio of journalistic skills, girded by omnivorous curiosity and unflagging brio, devotion to truth and mettle in its pursuit. An apostle of the ideal of a newspaper as much as its practice, his books on press freedom, history, photography and tradecraft (the latter in five volumes) further attest to a core passion forged as a child of the “self-consciously respectable working class” around industrial Manchester in the 1930s.

During his golden years as editor of the Northern Echo (1961–66) and Sunday Times (1967–81), this rare blend of qualities propelled a chain of power-shaking scoops on many topics: from air pollution and cervical smear tests, through corporate tax avoidance and espionage cover-ups, to the blighting foetal deformities caused by an unsafe pregnancy treatment produced by the multinational Distillers company. Such hard-won breaches in the ramparts of official and corporate secrecy helped change laws and lives.

These two decades of editorial clout, fortuitously aligned with the liberalising arc of the 1960s and 70s, were the pinnacle in a working life of astounding longevity. Their foremost legacy is a perpetual glow around the very name of Harold Evans. Understandably so, for by turning both the Sunday Times’s “investigative journalism” and its “Insight” team into kinetic brands — then, at their climax, invoking editorial independence to resist Rupert Murdoch’s effort to sack him — he made himself one too.

The overlaid memory of that joust, as of Insight’s prosecutory storylines and courtroom skirmishes, would seal Evans’s reputation, and be reflected in many awards from his peers, from the worthy (two press institutes’ gold medals for lifetime achievement) to the cringy: an ever-trumpeted 2002 choice by a self-chosen handful of readers of the British Journalism Review and Press Gazette as “greatest newspaper editor of all time,” above twenty other nominees, all British and male, many distant and long unsung.

In the latter case, Evans’s tour de force acceptance essay (“My first thought was to check out the obituary page of The Times for reassurance”) paid those forerunners rich tribute, claimed a retroactive vote of his own, drew precepts from a tour of his greatest hits — and thus, in overall effect, flattered the wisdom of the exercise and its verdict. At seventy-four, Harry’s showmanship and genius for self-promotion, as much as his sheer panache in making words sing, were undimmed.

Decades earlier at the Sunday Times, a thriving paper known for “exposure reporting” long before Evans’s arrival, many had shared in the credit for its next-generation coups. Its burgeoning Insight squad, with Phillip Knightley, Bruce Page and Murray Sayle among the paper’s self-styled “Australian mafia,” continued to deliver the goods, far-sighted editor-in-chief Denis Hamilton the guidance, munificent proprietor Roy (Lord) Thomson the funds. The unstinting Evans, a wizard of publicity to match his editorial flair, was the catalyst. “Harold could be wild and impulsive, but he had the sort of crusading energy a Sunday editor requires,” Hamilton would say of his appointee, this much-recycled utterance invariably losing a qualifier: that Harold had “need always for a stronger figure behind him to see that his talents were not wrecked by his misjudgements.”

A midlife switch was to freeze Evans’s newspaper romance in aspic, and his early fame with it. In plain terms, a vain year-long shutdown of Times Newspapers Ltd from November 1978, sparked by printing unions’ staff demands and resistance to new technology, led to the company’s papers (including the daily Times) being auctioned. From a scrum of financial and political intrigue, Rupert Murdoch’s News International emerged in March 1981 holding the murky ball (“the challenge of my life,” said the tycoon, describing Evans as “one of the world’s great editors”).

Evans was persuaded to become editor of the Times, across a short bridge at the papers’ joint works at Thomson House on Gray’s Inn Road. But a fractious year later he was asked by Murdoch to resign, which he did after holding out for a week (itself a media sensation). Evans’s eventual formula was that he resigned “over policy differences relating to editorial independence.” His embittered memoir of the saga (Good Times, Bad Times) complete, he relocated to New York in 1984 with his second wife, zippy magazine editor Tina Brown, working there for Atlantic Monthly Press, editing US News & World Report and launching Condé Nast Traveler. Then, from 1990, he was publisher at Random House, where Joe Klein’s (initially “Anonymous’s”) Primary Colors was among his successes. Propulsive coupledom, reaching its zenith in the mid 1990s, buoyed his profile, as would his steadfast bashing of Murdoch (not least during the Leveson press inquiry of 2011–12) and of resurgent threats to the type of journalism he cherished.

This disjunction in Harry’s career — the ultimate British newspaperman turned transatlantic celebrity publisher — would always make it hard to see the whole. More so, as the surface contrast between its two halves was acute. Where the fitful second was laced with high-end networking and lucrative dealmaking, the first had a perfect narrative arc whose climactic duel simulated a mighty clash of values. The fact that martyr and villain stuck fast to their allotted roles (or could easily be portrayed as such) kept the storyline ever exhumable. On occasion their paths would cross, as when Murdoch’s own manuscript briefly landed on Evans’s desk. “The wheel of fortune makes me your publisher as you used to be mine,” wrote Harry, leading Rupert to call the whole thing off.

In that first half, the dramatic symmetry of Evans’s long rise and slow-motion fall also fitted the culturally potent image of the valiant journalist or editor. His Panglossian autobiography My Paper Chase: True Stories of Vanished Times, published in 2009, evokes the “newspaper films” of his childhood: “I identified with the small-town editor standing up to crooks, and tough reporters winning the story and the girl, and the foreign correspondent outwitting enemy agents.” That art’s blessing was a life in its image conferred on Evans a halo, dutifully polished in Britain’s media circles whenever his name came up, to which the details of his American experience (including citizenship, in 1993) would add not a speck.

As in the movies, uneven reality — in this case Evans’s editorial virtuosity, the feats (ever more roseate) of those Northern Echo and Sunday Times years, and the events of 1981–82 — was tidied into a seamless fable. His exit from London allowed it room to grow; fond tales of the press’s glory days gave it regular watering. A trade entering the digitised rapids could do with a hero to muffle its fears, and Evans, epitome of the age now under siege, was in a class of his own. •

This is the opening section of an extended essay on Harold Evans, which can be read here.

The post Harold Evans, a seamless fable appeared first on Inside Story.