The past is another planet – they do things differently there. This monochrome dream-epic of medieval cruelty and squalor is a non-sci-fi sci-fi; a monumental, and monumentally mad film that the Russian film-maker Alexei German began working on around 15 years ago. It was completed by his son, Alexei German Jr, after the director’s death in 2013. If ever a movie deserved the title folie de grandeur it is this, placed before audiences on a take-it-or-leave-it basis: maniacally vehement and strange, a slo-mo kaleidoscope of chaos and also a relentless prose poem of fear, featuring three hours’ worth of non-sequitur dialogue, where each line is an imagist stab with nothing to do what has just been said.

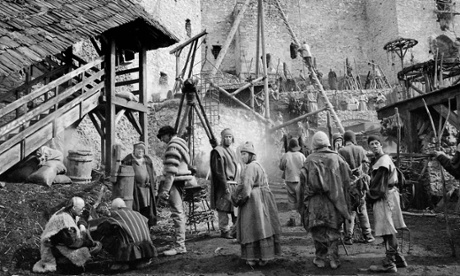

What on earth does it mean? I have my own theory, of which more in a moment. Hard to Be a God is based on the 1964 novel by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky, whose later work Roadside Picnic was filmed by Andrei Tarkovsky in 1979 as Stalker. It is set in what appears to be a horrendous central European village of the middle ages, as imagined by Hieronymus Bosch, where grotesquely ugly and wretched peasants are condemned to clamber over each other for all eternity, smeared in mud and blood: a world beset with tyranny and factional wars between groups called “Blacks” and “Greys”. In the midst of this, what looks like an imperious baronial chieftain called Don Rumata, played by Leonid Yarmolnik, walks with relative impunity: this sovereignty is based on his claim to be descended from a god.

And in a way it is true. Because this current location is an alien planet, eerily and exactly similar to our own, and Rumata is a secret observer or interloper from Earth. How he arrived there is a mystery. There are no scenes of him hiding a spaceship with branches or secretly reporting back to base with some incongruously non-medieval bleeping transmitter. He has gone native so thoroughly, and become so indistinguishable from the inhabitants, that his belief in his origins could be a delusion. But for a medieval earthling to have conceived such a futurist idea would be a sign of almost extraterrestrial genius – of the sort I’m now inclined to attribute to Alexei German. At any rate, our world and the other world are basically the same: it reminded me of Tarkovsky’s Solaris in this respect, and also his Andrei Rublev. (Another comparison is Monty Python and the Holy Grail, in which King Arthur was identified by the peasants, because “he hasn’t got shit all over him”.)

It really is authentically and awe-inspiringly insane, an unspooling nightmare of dismay, with long takes opening up a seamless surreal panorama. German appears to have overdubbed the dialogue (a little like Alexandr Sokurov) so that wherever they are spoken, lines sound like they are being intoned from within – which makes it all even more like a bad dream. There is a great deal of that Kafkaesque anxiety and wounded humour of the kind that German brought to the satires of the Stalin era from earlier in his career.

Each shot is a vision of pandemonium: a depthless chiaroscuro composition in which dogs, chickens, owls and hedgehogs appear on virtually equal terms with the bewildered humans, who themselves are semi-bestial. The camera ranges lightly over this panorama of bedlam, and characters both important and unimportant will occasionally peer stunned into the camera lens, like passersby in some documentary.

The most startling lines are those in which people complain about the lack of a Renaissance: “Where’s the art? Where’s the Renaissance?” moans one. In my view, this is the key. Just as in Narnia it is always winter and never Christmas, so in Hard to Be a God it is always the middle ages and never the Renaissance. Cultural and human advances never arrive in this alternative Earth, and what we are seeing is not the middle ages but the present day.

This is an ahistorical hell of arrested development, and also the film’s satirical core: whatever unimaginable advances have been necessary for interplanetary travel, they have brought us back to this dark-age swamp – and then been forgotten. We laugh at medieval maps that say “Here Be Dragons”, but we steadfastly refuse to consider the question of what, if anything, or who, if anyone, lies beyond our own planet, our own earthly existence; a willed blankness as fierce as the dragon-fearing forebears. Hard to Be a God creates its own uncanny world: it is beautiful, brilliant and bizarre.