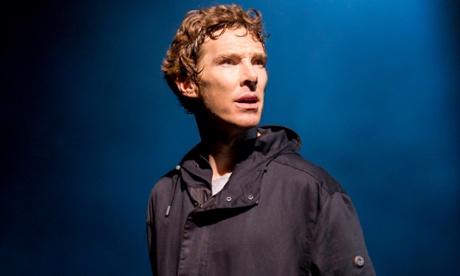

After all the hype and hysteria, the event itself comes as an anticlimax. My initial impression is that Benedict Cumberbatch is a good, personable Hamlet with a strong line in self-deflating irony, but that he is trapped inside an intellectual ragbag of a production by Lyndsey Turner that is full of half-baked ideas. Denmark, Hamlet tells us, is a prison. So too is this production.

What makes the evening so frustrating is that Cumberbatch has many of the qualities one looks for in a Hamlet. He has a lean, pensive countenance, a resonant voice, a gift for introspection. He is especially good in the soliloquies. “To be or not to be”, about which there has been so much kerfuffle, mercifully no longer opens the show: I still think it works better if placed after, rather than before, the arrival of the players, but Cumberbatch delivers it with a rapt intensity. He is also excellent in “What a piece of work is a man” and has the right air of self-doubt: in the midst of his advice to the First Player on how to act, he suddenly says “but let your own discretion be your tutor”, as if aware of his presumption in lecturing an old pro.

It is a performance full of good touches and quietly affecting in Hamlet’s final, stoical acceptance of death. The problem is that Cumberbatch, rather like the panellists in I’m Sorry I Haven’t a Clue, is given a lot of silly things to do. He actually opens the show, sitting in his room poring over a family album and listening to the gramophone, which denies us the propulsive excitement of the Ghost’s first entries on the battlements. Later, in assuming an “antic disposition”, Cumberbatch tries on a Native American headdress and then settles for parading around in the scarlet tunic and peaked helmet of a 19th-century infantryman. At one point he even drags on a miniature fortress – where on earth did he find it? – from which he proceeds to take potshots at the court.

Whimsical absurdity replaces genuine equivocation about Hamlet’s state of mind and the effect is not improved by having him later strut about Elsinore in a jacket brazenly adorned on its back with the word “KING”. All this is symptomatic of an evening in which the text is not so much savagely cut as badly wounded and yet which crudely italicises what remains. A classic example comes in the inept staging of the normally infallible play scene.

The whole focus should be on Claudius’s reaction to this mimetic representation of his murder and Hamlet’s eagle-eyed observation of his uncle. Instead, Turner starts the scene with the spectators in shadow and their backs to the audience. Even when they turn round to face us, Turner has Cumberbatch himself act out the lines of the villainous Lucianus. In consequence, Claudius’s abrupt departure seems less the product of residual guilt than a hasty response to Hamlet’s rude intervention.

The real problem, I suspect, is that visual conceits have taken the place of textual investigation. Es Devlin is a fine designer, but she and Turner have succumbed to the kind of giantism that marked their recent collaboration on Light Shining In Buckinghamshire at the National, which was rather like seeing Samuel Beckett reimagined by Cecil B DeMille. Here, Devlin has created a massive permanent set in which Elsinore resembles a decadent, baroque palace filled with wrought-iron balconies and Winterhalter portraits. I remember a similar design for a visiting Romanian production, but where that evoked the sleazy opulence of the Ceausescu period, this one falls apart in more blatant fashion. In the second half, the palatial set is filled with mounds of rubbish and overturned chairs, just in case we’d missed the point about Claudius’s collapsing tyranny.

One or two effects are striking, such as the gale-force torrent of leaves that invades Elsinore at the end of the protracted first half. But that is no substitute for the exploration of relationships. To take the most obvious example, just who are Claudius and Gertrude? For a couple supposedly bound together by reckless sensuality, Ciarán Hinds and Anastasia Hille show a remarkable lack of interest in each other and suggest nothing so much as a frigidly elegant pair used to giving cocktail parties in the Surrey hinterland.

Aside from Cumberbatch, there is only a handful of interesting performances. Leo Bill’s Horatio is a stalwart, backpacking chum, Jim Norton makes Polonius an anxious fusspot who even reads out his carefully prepared advice to Laertes, and Sian Brooke is a genuinely disturbed Ophelia, with an equal devotion to Hamlet and the piano. But it says much about the evening that its single most memorable moment is a purely visual one: Ophelia’s scrambling final exit over a hill of refuse, watched by an apprehensive Gertrude.

I am not against radical new approaches to Shakespeare. But this production does nothing more than reheat the old idea that Hamlet is the victim of a corrupt tyranny and is full of textual fiddling. To take one tiny example, Gertrude here tells us that Ophelia drowned herself where a willow “shows his pale leaves in the glassy stream” as if we were too dumb to work out the meaning of the original text’s descriptive epithet, “hoar”.

The pity of it is that Cumberbatch could have been a first-rate Hamlet. He is no mere screen icon, but a real actor with a gift for engaging our sympathy and showing a naturally rational mind disordered by grief, murder and the hollow insufficiency of revenge. He reminds me, in fact, of a point wittily made by George Eliot in The Mill on the Floss that, if his father had only lived to a good old age, Hamlet might have got through life with “a reputation of sanity, notwithstanding many soliloquies and some moody sarcasms towards the fair daughter of Polonius”.

Cumberbatch, in short, suggests Hamlet’s essential decency. But he might have given us infinitely more, if he were not imprisoned by a dismal production that elevates visual effects above narrative coherence and exploration of character.

-

At the Barbican until 31 October. Box office: 020-7638 8891.